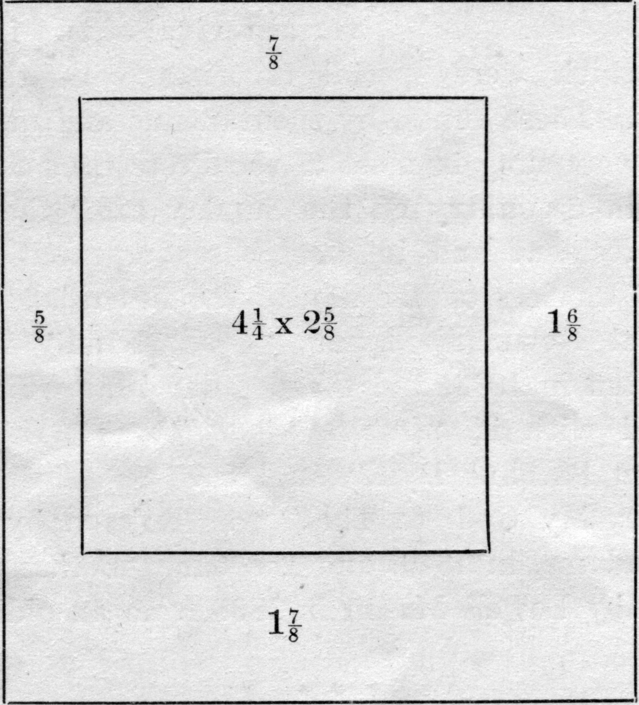

The appearance of the Book of the “Saturday Club,” of Sacramento, Cal., starts the question of how a club-booklet should be made. The publication in question is by far the handsomest musical- club book the Editor has ever seen; it shows refinement, taste, and good breeding on its face, and is a model of its kind. Its cover is French gray; the name of the club is embossed, but not printed in color. Its title-page contains all necessary information in a block of type at the upper left-hand corner, and is otherwise plain. The paper is rough, deckel edged, of good quality, the print refined and clear, and—here is the crucial test of a well-made book, the relation of the type-body to the margins is exactly right. The entire page is 7 by 5 inches. The type-body is 4-1/4 by 2-5/8. The upper margin is 7/8 inch; the inner margin 5/8; the outer margin is 1-6/8; the lower, 1-7/8. This disposition of the type-matter gives a very sumptuous effect to the book. Had the type-matter been put in the middle of the page, or, as we have seen it, even dropped below the middle, the whole style would have been altered and made common-place.

The rule for making up a booklet is: Let the upper and inner margins be comparatively narrow; the outer and lower margins wide. If there is necessarily an economy in margin, the inner should be narrowest, the upper less narrow, the outer wider, and the lower widest. Or the upper and inner may agree, and the outer and lower be alike.

The rule for making up a booklet is: Let the upper and inner margins be comparatively narrow; the outer and lower margins wide. If there is necessarily an economy in margin, the inner should be narrowest, the upper less narrow, the outer wider, and the lower widest. Or the upper and inner may agree, and the outer and lower be alike.

The propriety of the headings of the present booklet is also a matter for imitation. The resources of the job-printing establishment in respect to “fancy type” are appalling. It is scarcely possible to conceive of anything more offensive than the average booklet, with headings big enough for newspaper “scare-heads,” and broken, weak, vulgar body-type, filled out with leads where the words did not happen to justify, badly proof-read, and clothed in a loud, pink cover.

The type of a booklet need not be as small as in the present case: this size was undoubtedly selected to carry the amount of matter. The effect would have been more vigorous had it been larger; it is redeemed by the admirable press-work. A larger font would, under ordinary circumstances, be better.

The booklet may consist of eight, sixteen, twenty-four, or thirty-two pages: any multiple of four. The paper folds in such a way as to make this relation of numbers obligatory. You could not have a ten, a fourteen, or a twenty-one page booklet, in the nature of things. Sixteen pages folded together make a “signature”; a book may be arranged to print in ratios of one and one-half signatures, or half- signatures.

On making up the booklet, then, get a large sheet of paper, and fold it so as to get the number of pages required in the right size. Number them, and, beginning with the title-page, jot down the headings of their contents. This is a trial dummy. When the booklet is thus laid out, make a specimen-page by preparing one of exactly the specified size, ruling the margins precisely as required, and writing down in each spot alluded to its exact size. Now, the printer knows exactly what is required.

The next thing is to prepare the literary matter so that it will not require any changes from copy. You determine the amount of your type-matter by the square inch. Ascertain how many words you have written, allowing for headings; ascertain also the number of words contained in a square inch of set type the size you desire to use. The number of pages required then becomes a problem of division. Most printers have specimens of their body-type set to compute by. They allude to their type as containing so many ems to the inch. M is a square letter and their unit of measurement.

Job-printers charge from thirty to fifty cents an hour for alterations in proof from the copy submitted them. It is therefore worthwhile to have every word settled precisely in the type-written copy. Then comes choice of type. This permits a latitude as wide as the choice of subjects; but type set solid—i.e., without small spaces between the lines—is much stronger than the same type “leaded”; too much lead weakens the effect.

When the type is chosen, keep the composition in it. If necessary to have a second style for the headings, be sure the two match in style, depth of color, and general effect. Stop there! Three different kinds of type on one page are perilously near vulgarity, and when this number rises into twelve (we have seen twelve on one single program) the effect is as disgusting as ignorance and bad taste could combine to make it.

Avoid the stock head and tail pieces that the printer loves to introduce. Abhor the hideous geometrical stamps with which he buttresses his title-pages, the vinous spirals, and depressing triangular emblems. Handsome, elegantly-cut type needs no cheap ornament.

When the book-pages are set, read, and numbered, the printer comes to the fore. Then it behooves the maker of the booklet to see to it that his matter is printed so that the top of the odd is on a line with the top of the opposite even page. Here the job- printer is at his worst. His pages are as rough as a corduroy road; a glance at their straggling ranks is a lesson in misrule. It is his last revenge, for you never see it till the work comes home for distribution. Argue with him betimes; you will then avoid recriminations and disappointments.

Avoid hard, stiff, coated paper. It always weakens the effect. Half-tones require it; but the average booklet can be printed upon book-paper, and will be cheaper and handsomer.

ON THE THE WOMAN’S CLUB AS A CO-OPERATIVE BUSINESS.

There is no more valuable element in the training which the woman’s club is giving American women than that offered by the relations of the club to business life. The difference between business ethics and family ideas is very marked. Women continually transgress the boundaries of business honor unconsciously. This uncertainty as to the outcome of dealings with women makes men dislike to transact business with them; but there is no better school than that offered by club-life, in which to get at the responsibility attaching to statements and promises in an arena where financial results depend upon the exactitude of the speaker.

The club, however, should be more than a training for business: it should involve more or less business in itself. Every club has a “treasury.” The filling of this treasury is simply the management of a business more or less extensive. The present writer is inclined to advocate the enlargement of this department of club-life.

There are many ways of filling the club-treasury besides that of levying dues upon the members. A book-club, a quartet-club, or a weekly music meeting probably needs no more elaborate financiering than this; but the fully organized woman’s club with its multifarious activities, does require very many more avenues of income and very much more business tact in its development. The secret of making such a club successful lies, in my opinion, in making it into a stock company. There are gentlemen’s clubs in New York which not only own property, but grow rich year by year. The Grolier, for instance, is a publishing club; its limited editions of fine books always sell at large prices, and the club not only owns its house, but possesses an invested capital. Every member of it has a share of the club capital, amounting to $500.

The Players’ Club is another successful society which is year by year increasing its capital and investing its surplus. There are many such in the metropolis.

It would be better for a woman’s club, however, to form itself into a company in which membership should constitute the ownership of one or more shares. It would then be a matter of personal as well as mutual interest to carry through the financial undertakings of the association, and other reasons besides those purely emotional would draw the members together.

For instance, the objects usually designated as most desirable for the village mite societies, teas, and theatricals would thrive better were the little sums annually collected and dispensed at the end of the earth made the foundation of the multiform activities of a club, with its prospective club-house and varied resources of culture and philanthropy.

Every village ought to have its “Woman’s Club-House,” with its free reading and social rooms, in which the wage-earners of the community could enjoy social pleasures under protected conditions. The writer well remembers the need of such an institution in a country village where she once lived.

Dozens of the young people, as she remembers, used to make a daily pilgrimage to the railroad station to see the trains come in. The bare interior of the waiting-room offered the only neutral ground in the town for the harmless interchange of the little flirtations that were the staple amusement of its occupants. A club-room owned and managed by the ladies of the town would have supplied a much more healthful opportunity for social intercourse.

A club stock-company has responsibilities. Its shares may yield dividends; but they may also be assessed. Were such possibilities involved in the success of club concerts, classes, and teas, it is tolerably certain that the stockholders would work much harder to produce a successful issue of the club enterprises.

Were the selling of seats for an orchestral concert certain to result in a personal benefit, or neglect to sell likely to bring about a personal loss, those seats would be sold.

When men are appealed to to forward some scheme of philanthropy they are sure to say: Put it on a business footing. That is because they know by experience that the element of gain or loss is indispensable to success. It is exactly the same with women’s enterprises. Pure altruism does not bring out as good results as community of interests.

Money is not difficult to obtain when enthusiasm is at working heat. The difficult thing to arouse is enthusiasm. Nothing is so dampening to enthusiasm as being asked to work hard to forward the wishes and interests of your neighbor to the hindrance of your own private feelings. Now, the stock-company is a device by which men can be so drawn together as to work for their own mutual interests against the grain of personal feelings. That is, one interest outweighs another, and the corporation moves on. Some such method of organization is much needed in women’s clubs. Undoubtedly the property interest is at once the strongest and best for the purpose.

The business maxims which should control those club activities which involve money at all are: (1) make everything undertaken pay a little more than its expenses; (2) never allow money once made to slip away. Invest all gains at a profit, and make new enterprises yield new returns. Planned in this way, those comfortable words “surplus,” “sinking fund,” “capital,” would begin to play a part in women’s imaginations, and the economic value of co-operation would become apparent.

The lending library; the tea; the recital; the lecture course; the quartet club; the concert season; the language, sight-singing, and elocution classes should all yield a slight profit. If men managed them they would, because “they would have to.” If women feel that they must come to such conclusions, they will achieve the same result. Once in possession of capital, luxuries follow as a natural sequence; and music managed on business principles gains in dignity, scope, and power. By all means put your club into business trim, if you wish it to be strong, lasting, and valuable to the community.

* * *

SYMPHONY DAY.

Two years ago “Symphony Day” in the musical club was a modest experiment; now it amounts to an established institution, for it has become our regular custom to have a symphony for every fourth meeting. Meeting fortnightly, we have but five of these days in a year, but it gives us a chance to become somewhat acquainted with the great symphonic writers. One work each of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann has been our choice for the current year. And we find our symphony studies a great help toward intelligent accent and phrasing, and also in the appreciation of the tone-qualities, and of the work of the different instruments represented.

On our club calendar as many ladies are appointed to render the work as the symphony has parts; and the president, at her own convenience, also appoints understudies; so that, if any of the appointed ones should fail us at the critical moment, there will be someone ready to step into the breach, and the symphony will not be marred by the loss of any of its parts.

As we make use almost entirely of the four-hand editions, and as each appointee is at liberty to ask any other club-member to be her “Secondo” (herself taking the “Primo”), it is quite possible for eight members of the club to be enlisted in the service, on one work, irrespective of the substitutes. When the fateful day arrives, both regulars and understudies come well charged with music—and zeal. And those whose services are not absolutely demanded have yet reaped the benefit of the labor, and can doubly enjoy the music, because all have become more or less familiarized with the work in hand.

Especially interesting is the symphony story, which is read by the hostess of the day, as a preliminary to the musical part of the program.

The “guest-problem” we have solved in the following way: each member is allowed to invite one visitor to each meeting; and we have evolved a way of making our guests “work their passage,” as it were.

For, as they are often musical themselves, it is understood when we invite them, that we should be pleased to have them contribute to the afternoon’s entertainment, by performing, after the club program is finished. This little plan does double duty, like the useful front gate that swings both ways: It militates against uncharitable criticism on the part of our guests, and then, when they, in turn, are called upon to perform, we are often charmed to find that we have been entertaining unawares, not an angel, perhaps, but what is more to the club-purpose: a very desirable candidate for membership. In this safe and quiet way we are enabled to keep our ranks comfortably filled, without going outside our own gates to do so.

We are very careful in our selection of members, and are apt to become the more attached to them as time goes on, for this very reason. What we most desire is steady, reliable, workers, for as The Etude has justly observed, “Comradeship is the object to be sought in club-life, and it is labor and nothing else that makes comrades.”—C. A. Browne.