Written Expressly for The Etude by the Eminent British Composer

SIR CHARLES VILLIERS STANFORD

"Man is all symmetric,

Full of proportions, one limb to another."

—George Herbert.

It has been said that the dividing line between genius and insanity in the individual is thin. Possibly so; although in actual life the crossing of that line is comparatively rare, and in creative music at any rate the cases which have occurred are generally traceable to physical causes wholly unconnected with the practice of the art. In the series of great composers of past times from Palestrina to Wagner and Brahms, there is only one instance of insanity, Robert Schumann; and his brain trouble was proved to be the result of a malformation of the inner surface of the bones of the skull, and had nothing to do with the organ itself. He continued to write while the disease was progressing, but the only sign of it was a tendency to gloom, and a dulling of the sharper edges of effect. There was no distortion of ideas or of phrases, and no loss of grasp in form and design. Insanity is the opposite pole to idiocy. It is not due to lack of power in a degenerate brain, but to a "fault" (in the geological sense) in a brilliant one. In many cases the brilliancy is enhanced by the abnormal condition itself, and some of the most witty and sparkling sayings have been noted from the lips of men who, though clever when in health, became uncannily so when the mental balance was disturbed. The immortal saying "Heaven lies about us in our infancy, but that is no reason why we should lie about heaven in our old age" is one striking instance in point.

How far then can we speak of insanity in music? I take leave to hold the opinion that such abnormality as now exists is the result of a calculated and mock insanity, which is utilized to excite and to play upon such morbid and hysterical emotions as it can find in the public. Mad painters do not lose all sense of color, drawing and design, if they continue to work; neither do mad composers. Such manifestations of reckless cacophony as have recently been foisted on the public ear do not come from the asylum but from the factory; they are machine-driven and machine-made; the only question is whether they will succeed in qualifying some of the audience to be inmates of the building from which they pretended to emerge. A century ago a physician in Berlin, who was once consulted by a deaf patient in the hope of recovering his hearing, carried him off to hear an opera by Spontini, then reputed to be the noisiest writer for the orchestra alive; afterthe first act the patient turned to his doctor with a delighted expression and exclaimed: "I can hear!" But the doctor took no notice—he was deafened. History is repeating itself nowadays on a large scale. To the real music-lover, attendance at a concert is becoming more of a pain than a pleasure, and the ears of the groundlings are being tickled by the appeal of sophisticated ugliness. The fault does not lie at the door of the unthinking part of the public but at that of the charlatans who are imposing upon them. When the public gets a good sound lead, it may be trusted to follow it; when it is hypnotized by a false one, it may too easily fall into the trap, and become the prey of the professors of the confidence trick. These gentry know their business too well not to profit by it, and their returns are too large to encourage them to forsake the ways of chicanery for an honest livelihood.

Whence did this systematized cult spring? In the present, as in the past (for the world has always had its attacks of ugliness-worship) from an attempt to carry on a policy of freedom until it degenerated into license; from a distortion of courage into recklessness; from a tendency to ride a new theory to death. Some of the most gifted composers have succumbed to the wiles of this siren; most of them have done something, a few of them a good deal for the advancement of some details of the art in the process. Monteverde did so in the old Florentine days; the results of his experiments however only survive in the better workmanship of the sounder masters, who could sift the chaff from his grain; but his music is a dead letter, while Palestrina's is not. In later times Berlioz, a red-hot reformer who carried realism to the point of extravagance, considered that beauty was secondary to vividness and force (though he was undoubtedly sincere in imagining that he was equally endowed with all these qualities), but who, save the conductors who revel in the driving of a restive four-in-hand, has an undiluted enjoyment in listening to his great conceptions? Yet Berlioz too did yeoman's service in adding to the pigments available for the orchestral palette. And after him, Liszt. The historian of the next century will have no hesitation in tracing most of the present-day aberrations to that personally fascinating and essentially superficial master.

In his earlier days dominated by the personality of Chopin, he did much for the repertoire of the pianoforte and for enhancing its technique. In his later, he tried to penetrate into regions which he had not the thorough equipment to explore, concealing his inability to develop themes by preaching the insidious gospel of merely repeating and transforming them, and by encouraging a flirtation between the stage and the concert room which led to disastrous results. His "symphonic" poems, which have none of the qualities of symphony, however they may claim an affinity with poetry, opened the door to the dangerous theory that absolute music can express situations and emotions which alone can be made clear in dramatic action on the stage. Without a title and an analysis they are unintelligible, and cannot stand alone. To the fatal consequences of such a propaganda, the contemporary composers of both schools, instrumental and dramatic, were fully alive. The well-known manifesto signed by Brahms and others is the record of the former, the conversations of Wagner with Dannreuther of the latter. Of the two Wagner, although he did not mention Liszt by name, is the more drastic and detailed: and it will bear quotation here. (The italics are mine.)

"Give me Beethoven's quartets and sonatas for intimate communion, his overtures and symphonies for public performance. I look for homogeneity of materials, and equipoise of means and ends…. In instrumental music I am a Réactionnaire, a conservative. I dislike everything that requires a verbal explanation beyond the actual sounds. For instance, the middle of Berlioz' touching scène d'amour in his Romeo and Juliet is meant by him to reproduce in musical phrases the lines about the lark and the nightingale in Shakespeare's balcony-scene, but it does nothing of the sort—it is not intelligible as music… . Whenever a composer of instrumental music loses touch with tonality he is lost… . When occasion offered I could venture to depict strange, and even terrible things in music, because the action rendered such things comprehensible: but music apart from the drama cannot risk this, for fear of becoming grotesque." He instanced also eight bars in Lohengrin as an example of modulation too far-fetched to be intelligible except in connection with the dramatic situation, and which would be a blemish in pure instrumental music.

Thus, out of the mouth of the greatest progressives of the nineteenth century, do the works and principles of the Liszt school stand condemned. Sanity in music had no sterner champion than the man whose style and methods of expression have been so lavishly and even unscrupulously drawn upon in the making of a music with which he had no sympathy at all. It is a half-bred progeny which has come of this ill-assorted union of concert-room and stage; and common-sense, let alone good taste, will presently find it out, and treat it as déclassé.

Angles and Curves

When an epidemic breaks out in some locality, experts conceive it to be their duty to investigate the causes, and to take steps to stamp them out. No art is proof against attacks of disease, and it is no very difficult matter to get at the microbes which give rise to it. Painting no less than music is having at this time one of its crises of abnormality. It has had several in past days; one of them is to be seen in the Musée Wiertz at Brussels, where the artist rebelled against the limitations of a frame, and painted figures climbing round it out of his picture. In the present time it is taking the form of the angle versus the curve, and no doubt the intentionally perverse persons who are preaching and practicing the religion of the angle (not without pecuniary profit) will presently hold that the world is square, or if it is not that it should be. If this eccentricity did not pay, as a succès de curiosité, it would cease as quickly as it began. The disintegration of color, which is another of the fads, may be, as some hold, a symptom of insanity, but it is much more likely to be the deliberate expression of a sane person who has studied insanity. Distortion is the keynote of these propaganda. Nothing is to be portrayed as the natural human eye sees it, and if the owner of the eye protests, he is told that he ought to train it to see—better. In some modern musical tendencies we see the same process at work. It is no longer "the thing" to writea simple chord of C Major.

It must be encrusted with some note foreign to its nature (usually A) to bring it up to date.

Not so long ago it was a habit with organists to put in aB to give the chord, as they used to say, "a fine rolling effect."

These men were dubbed Philistines and antiquated donkeys, their rolling effect was squashed, and the chord restored to its pristine purity, only to find itself attacked by the advanced and Precious school, and anA put in instead of the objurgated B. The natural human ear prefers to be let alone and in spite of all temptations remains faithful to the acoustical value of the pure chord. It is a well-known phenomenon that taste as well as sight and hearing can be made to accustom itself to what is inherently nasty, and can even develop an abnormal liking for the most repulsive solids and fluids.

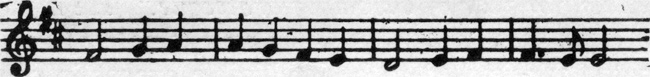

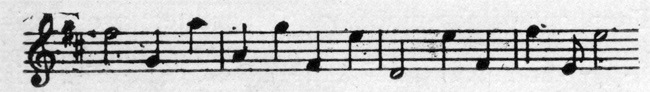

One well-known musician preferred an ancient egg to a fresh one, on the ground that antiquity added to the flavor. Several persons within my knowledge have relished cod-liver oil as if it were champagne. No human beings would venture to claim that such tastes are normal, or healthy: yet in matters of art they are expected to admit that equivalent eccentricities are the natural and healthy condition, and that the inborn instinct of the individual is false and unsound. Distortion is the most malignant of the bacilli. It also takes the form of substituting skips for direct motion in a melody. For instance the theme of the Choral Symphony would find no favor in the eyes of these "progressives." Instead of

it would become

so as to escape the accusation of being "obvious." Unfortunately however the tunes (if any) which composers of this type produce are so inherently poor, that the lack of invention, which is so patent to anyone with ears to hear, has to be perforce concealed by this kangaroo method, or detection of their poverty could not have escaped. Another tenet is that all such things as rules are to be ignored because they have been called rules. Certain progressions which the great masters have condemned for their inherent ugliness and uncouthness, not from red tape considerations but from acoustical experience, are adopted as essentials, not because they are in the least degree more beautiful than they used to be (the laws of nature prevent that), but simply and solely because the great masters said "don't do it."

It must be admitted that for this not altogether unnatural spirit of rebellion, the teachers of technique have been largely to blame. If they had explained the true basis of the inadvisability of these progressions, and substituted reasoned advice for "prohibition" there would have been far less kicking against the pricks. There is practically no red tape "rule" in art; neither is there any "rule" which a master cannot break if he knows he is breaking it and has sound reasons for so doing. But he has to be a master of proved and sound good taste to be able to violate principles which his great predecessors have adopted, not for the purpose of irritating their successors, but for preserving the canons of beauty. Similarly there is a tendency to rebel against form. But the plan of the universe predicates the necessity of form everywhere. Art is but an idealization of certain aspects of that plan. A great landscape painting is never a photographic reproduction of nature; if it were, it would be accurate enough but merely a dry record of facts and objects. It is, in practice, a view of nature as it appears to the eye of a poet and idealist. But if the mountains were represented peaks-downward, and the trees roots-upward, or if the canons of perspective were ignored (as in Hogarth's famous skit) the result would be a grotesque absurdity, precisely because the laws of nature were broken in the one case, and the laws of optics in the other.

Music is more intangible, and the difficulty of coordinating the laws of nature and the laws of acoustics is greater and more elusive. Moreover, the ear is often, in its natural state, less acute and less capable of close analysis of details than the eye. The uncultured ear of a beginner will often fail to appreciate an ugliness or a crudity which it will assuredly condemn when training has done its work. It has been more or less proved that there is no such thing as a wholly unmusical ear, except from physical defect, and that many apparently tone-deaf persons can be made to hear and appreciate musical sounds, thereby proving that their hearing organs are not deaf but asleep. This is but the lower stage of a process, which in its higher stages marks the difference between an ear which is insensitive to careful analysis of detail and one which has been trained to appreciat (sic) it. A few, like Mozart, had this quality ready-made; most people, even those who have become great musicians, have had to work hard to possess it.

The Emptiness of Cacophony

The musical public must not be presupposed to possess this finely analytical ear, and it is for composers not to exploit that fact to excuse their own lapses from beauty, as it is their bounden duty to use their powers to increase their sense of it in directions which are, if progressive, always legitimate. There is often, in these days of quick traveling, rapid action, and high pressure, a hankering after something to tickle jaded palates, and to astonish rather than to elevate taste. Anything which gives a shock is liable to appeal to this hysterical tendency. The music which ministers to this abnormal craving is doing infinite mischief to those who sit and listen to it, and the degradation of good clean art is certain to ensue. Accustom a child to restrict its diet to sweets and curries, and he will suffer for the absence of good solid food in after life. So it is with those musical children, the public. They are just now in the mood to accept any imposture, if it is only exciting enough, and sufficiently striking to arrest their attention. They would even revel in a lecture which set out to prove that black is white: or that the earth is flat. They set the quack above the physician. The cranks (like the poor) are always with us: but they are happily in a minority. The majority, unfortunately, in Northern Climes do not hiss, and the minority, in consequence, claim that they accept what in their hearts they loathe, and only tolerate for the sake of a little extra excitement. The apostles of ugliness meantime prosper, and will continue to do so just as long as and no longer than the public allow it. End the profits, and the purveyors of peppers, curries, ancient eggs and cod-liver oil will suspend business. The popularization of music of real value and sound progressiveness is and always has been a slow process. The very rapidity of the spread of cacophony is a proof of the emptiness of its appeal. The war, with all its attendant horrors, has at least one virtue to its credit, in that it has already brought home to the suffering nations the beauty of simplicity, and done much to strip off the gew-gaws of the cranks.