Berlioz came into the world just as the French democracy, that allowed Robespierre to barter his insatiable ambition for his life, was merging into the Empire which was to offer Napoleon a similar tragic opportunity. In 1804 “the little corporal” importunately snatched the crown from the hands of Pope Pius VII and placing it upon his own head with his own hands declared himself Emperor of France. During the childhood and youth of Berlioz he saw upon all sides the significant “N” of Bonaparte. France was ascending to new power and new glory. Berlioz was all patriot. He loved his France and particularly his Paris. Mercurial at all times, his disposition and life experiences were not unlike the fortunes of his native land. During his entire life the French people seemed to be struggling for republican freedom —a freedom, which did not arrive in anything like a permanent form until the year after the death of Berlioz.

BERLIOZ’S ANCESTRY AND YOUTH.

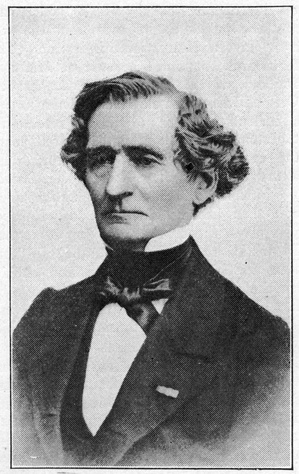

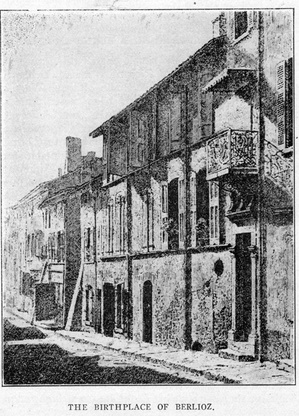

Hector Berlioz (pronounced Bair-lee-ohs) was born at La Côte St. Andrè, near Grenoble, on Dec. 11th, 1803. His father was a country physician who was determined to have his son become a great surgeon. In the home every possible attempt was made to suppress the boy’s very manifest love for music. Berlioz had the greatest imaginable disgust for the horrors of the dissecting room, and whenever his father urged him to become a medical student he rebelled. Consequently when he went to Paris in 1822, for the purpose of entering the medical school, he found the Conservatoire far more inviting and spent most of his time in the pursuit of musical education. This resulted in a long domestic war between the parents and the talented son.

BERLIOZ’S PRIVATIONS.

Regarding his attendance at the Conservatoire as open disobedience, his remittances from home were discontinued and Berlioz suffered the direst poverty in his efforts to secure a musical education. In his autobiography he tells how he was obliged to take a chorus position in a minor theatre to get the bare necessities of life. There is an element of the tragedy in the case of this young man with great musical talents and ambitions, denied all through his youth the technical training which might have affected his entire career as a composer.

In his earlier years Berlioz had learned to sing at sight, play the guitar and flute fairly well, but he never mastered the pianoforte or the violin instruments which have proved so indispensable to other composers. Singularly enough, with this meagre executive ability he became the greatest authority upon instrumentation of his time. His discoveries in the realm of orchestration were so striking that he revolutionized many phases of the art.

Shut off from assistance at home, Berlioz was more determined than ever to become a great master. Accordingly he secured the interest of Jean Francois Lesueur, who became his teacher of composition. Lesueur, now forgotten, was one of the foremost musicians of Paris in the early years of the last century. As Master of the Chapel at Notre Dame and later for Napoleon he gained wide influence. He took a great interest in Berlioz and in a very few months we find our young musician writing a Mass for one of the Parisian churches.

AT THE CONSERVATOIRE.

Berlioz had some difficulty in securing admission to the French Conservatoire. As in the case of many another genius trying to secure a position in an institution conducted along conventional lines his talent was altogether ignored in face of his technical short-comings. Cherubini was then the director. Although Beethoven looked upon Cherubini as one of the foremost musicians of the time and Berlioz made a veritable god of Beethoven, there was little friendship between the director and the student. During the seven years, which Berlioz spent at the Conservatoire, he was in a constant state of turmoil. The student was a romanticist to the core while his teachers took a pride in being as academic as possible. They took it upon themselves to build a barrier of rules around each student and called that barrier education. Berlioz was regarded as a kind of musical anarchist to be repressed rather than encouraged.

THE PRIX DE ROME.

Finally, after many failures, due partly to his own technical deficiencies and again to the political maneuverings of his enemies in the Conservatoire, Berlioz succeeded in winning the much coveted Prix de Rome with a cantata La Mort de Sardanapale. This entitled him to two years in Rome and one year in travel in other continental countries. Berlioz was no sooner away from his Paris than he longed to return, and with the consent of the ministry back he journeyed in 1832. He had already written two of his well known works, King Lear and Symphonic Fantastique.

In his entertaining autobiography there is no part as interesting as that in which he describes his courtship and marriage with the Irish actress, Henrietta Smithson (1833). She was the rage of Paris in her day and Berlioz, who had developed a great fondness for everything Shakespearean, saw in Henrietta Smithson the actualization of one of his ideals. Berlioz, however, was in love with Juliet and Rosalind rather than with the one who portrayed them. Later in life his actress wife fell so far below his ideals that a separation became inevitable.

In his entertaining autobiography there is no part as interesting as that in which he describes his courtship and marriage with the Irish actress, Henrietta Smithson (1833). She was the rage of Paris in her day and Berlioz, who had developed a great fondness for everything Shakespearean, saw in Henrietta Smithson the actualization of one of his ideals. Berlioz, however, was in love with Juliet and Rosalind rather than with the one who portrayed them. Later in life his actress wife fell so far below his ideals that a separation became inevitable.

Berlioz’s marriage was undertaken at a time when he had little prospect of future income. In fact after the birth of his son he was obliged to devote so much time to writing newspaper criticisms that only a little time could be devoted to the actual work of composition. He had been turned down at the Conservatoire where he had applied for a position as teacher of harmony. Cherubini would have none of such a revolutionist. Had it not been for his ability as a feuilletonist he and his family might have starved.

HIS REMARKABLE PRODUCTIVITY.

Berlioz was a very rapid writer. Many of his critics contend that if he had written a little slower and taken more pains with his work he might have produced compositions of higher consequence, but Berlioz was a rhapsodist and wrote as he improvised. In fact in order to get his ideas down quick enough he was obliged to invent a kind of short hand notation. During the years immediately following his marriage he wrote the three symphonies. Symphonie Funèe et Triomphale, Harold in Italy and Romeo and Juliette, a cantata on the death of Napoleon; the opera, Benvenuto Cellini, the Requiem, and other works of smaller dimensions. Gradually his works became more and more popular and some financial return was received. This, however, came in the form of awards and gratuities rather than earnings. The French Government, for instance, paid him 4,000 francs for his Requiem and the violinist, Paganini, presented him with 20,000 francs for his Harold en Italie. Through this and other sources of income he was enabled to make a long-coveted trip through Germany. Liszt and Schumann had championed his cause so well that he was enthusiastically received everywhere. In fact his tour has been compared to a triumphal march and was quite different from the critical drubbing which the German composer, Richard Wagner, was then receiving in Paris. During the next few years he made tours in Austria and Russia, returning to Paris to produce his La Damnation de Faust. This work did not win anything more than very slight approval at the outstart. During the entire time Berlioz was abroad he strove to win popular favor in Paris by sending back bulletins of his great successes in foreign countries, but Paris was apathetic, and the more Berlioz knocked at her doors the sounder was her sleep. His next foreign ventures took him to England, whither he went four times between the years 1848 and 1855, meeting with success as a conductor.

SLIGHT RECOGNITION AT LAST.

In 1856 France began to show her appreciation of Berlioz by making him an Academician and later the Librarian of the Conservatoire. In 1854 Berlioz’s first wife died, and after a very short time we find him married again to a singer with very slender gifts, Mlle. Martin Recio. Despite the fact that she insisted upon taking the leading role in the performances of her husband’s works—often with disastrous results—he was greatly devoted to her.

Berlioz was profoundly affected by her death in 1862. He became still more disconsolate when the work upon which he spent the best labors of his life, Les Troyens, a grand opera in two parts (I. La Prise de Troie. II. Les Troyens à Carthage) failed after a very few performances (Paris, 1863). Not even the success of his little opera, Béatrice et Benedict, performed with much favor at Baden in Germany, could revive his inspiration. Les Troyens was his last work of consequence, and its failure worried the composer so that a rapid decline of his health followed.

THE DEATH OF BERLIOZ.

It has been said that it is a failing with the French to show their appreciation after death, but that after all is a common failing of all peoples. Berlioz died in Paris on March 3rd, 1869, and received a most pompous funeral. Ten years later all Paris turned out to an immense concert of his works given in the Hippodrome in commemoration of his death. Busts, statues, and all of the other pitiful means of petrifying his memory may be found around the great city that so long permitted him to starve in neglect.

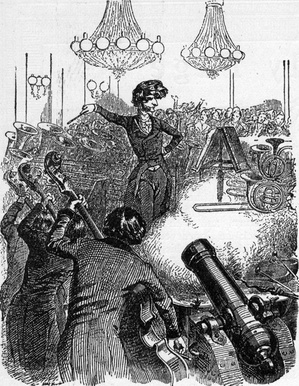

Much more might be said of Berlioz as a conductor than of Berlioz as a composer. He gloried in huge orchestras and once had one so large that it was necessary for him to have electrically operated metronomes stationed in different parts of the orchestra so that by controlling the beat from the conductor’s desk he might be sure of maintaining the tempo. In prescribing the instruments for his ideal festival orchestra he calls for the following: 120 violins, 40 violas, 45 ‘cellos, 18 three-stringed basses, 15 four-stringed basses, 4 octo-basses, 6 large flutes, 4 third flutes, 2 piccolos, 2 piccolos in D flat, 6 oboes, 6 corni inglesi, 5 saxophones, 4 tenoroons, 12 bassoons, 4 clarinets in E flat, 8 ordinary clarinets, 3 bass clarinets, 16 horns, 8 trumpets, 6 cornets á piston, 12 trombones, 3 ophicleides, 2 bass tubas, 30 harps, 30 pianofortes, 1 organ, 8 pairs of kettle drums, 6 drums, 3 long drums, four pairs of cymbals, 6 triangles, 6 sets of bells, 12 pairs of antique cymbals, 2 very low great bells, 2 gongs, 4 Turkish crescents—460 pieces in all. Surely the modern claims of Richard Strauss are modest in the extreme.

BERLIOZ AS A COMPOSER.

The work of Berlioz has been variously estimated by different critics. His greatest service to music was unquestionably his work in orchestration, where he was at once bold, artistic and ingenious. Those who place a low valuation upon his gifts as a composer do not hesitate to say that he provided the basis for much of our latter day orchestral treatment. His sense of color was extraordinary and in a way glossed over his technical deficiencies in composition and his lack of melodic inventiveness. While many of the melodies of Wagner became the common property of the masses, it is difficult to point to a single theme of Berlioz outside of the Rakoczy March which has been adopted by the public as its own, and the Rakoczy March is in fact a Hungarian inspiration. The Rakoczy March was so named because at first it was a lament for one of the great Hungarian heroes, Rakoczy. Originally it was a slow and solemn tune played upon an instrument (the tárogaté) resembling the oboe. It first appeared about two hundred years ago, but in the early part of the last century the same theme occurs as a march. Berlioz seized upon the theme and introduced it in his Damnation de Faust. The march then became the craze of Europe and Berlioz was given the credit of having been the composer. In justice to him it should be said that had it not been for his highly colored and skillful orchestration the famous tune might never have become so popular. In his autobiography Berlioz gives vivid pictures of the uproarious enthusiasm with which the march was received.

This does not mean that the music of Berlioz does not contain moments of greatness, but his lack of the substantial characteristics which have made the fame of such masters as Beethoven, Tchaikovsky, Franck and others permanent, must always dim the reputation of Berlioz. What Berlioz might have been had he had the right technical training early in life must always be one of those discomforting problems which baffle solution.

BERLIOZ AS A WRITER.

We are tempted to say that no more fascinating book has ever been written by a great composer than Berlioz’s Autobiography. His delineation of his own desires, mental attitudes and emotions is so remarkable that it has the charm, of a Thackaray, a Heyse and a Maupassant combined. It is one of the most interesting narratives of its kind. All through the work one is convinced that Berlioz is writing about the man he would like to be rather than the man he really is, but in this very angle of treatment we have revealed to us one of the intimate views of the composer’s character. Berlioz was in many ways a poseur. His appetite for renown amounted to an obsession hardly excelled by that of Wagner who, after all, could forget himself in his work. Nine volumes of the writings of Berlioz have been published, but the most interesting by far is the Autobiography, which reads from cover to cover like a fascinating novel.

His attitude toward other composers was unique. He placed little value upon Chopin, Schumann, Schubert, Bach or Handel. In many cases his investigations had been so superficial that he was hardly qualified to judge. Of Beethoven, Weber and Gluck he could hardly say enough.

His radical position in musical art made him the subject of much caricature, as well as invective. His replies were witty and sharp and he never seemed to lack ammunition, to fire back at his enemies.

DIFFICULTY IN ARRANGING A BERLIOZ PROGRAM.

It is a comparatively simple matter to arrange a program of the works of Richard Wagner which may be played in the parlor or the studio, although Wagner wrote but little outside of his huge music dramas. With Berlioz, however, the case is quite different. Without the color and fascination of the orchestra most of his works seem to be lacking in that broad human interest which would make them suitable for the ordinary recital or club program. In addition to this practically everything which might be adapted to a Berlioz program is either difficult or awkward for the performer. The Träumerei and Caprice for Violin, Opus 8, is about grade seven and is one of the most attractive recital numbers written by Berlioz. The Rakoczy March comes in various grades of difficulty and is almost always effective. The Gnomenchor und Sylphentanz from the Damnation of Faust comes in a splendid arrangement by Carl Tausig, of which a new edition has been made by Xaver Scharwenka. This, however, is suited only to the concert pianist. The Serenade of Mephistophele has been arranged for piano by Dr. William Mason. This arrangement, while not particularly difficult, is not especially effective. The Villanelle from Summer Nights is a really excellent song from the musical standpoint, although difficult for the singer, owing to the incessant high range.

Berlioz’s best song La Captive, one of his masterpieces, calls for a voice of large range and power. It is a concert song in the bigger sense of the term. The student should remember, however, that most all of Berlioz’s orchestral works are wonderfully effective, rich, and brilliant when heard on the orchestra. In fact, there is no department of musical composition that was not quickened by the efforts of this remarkably active man. Ernest Newman, the well known English critic, has shown how Berlioz brought new life to the Opera, the Symphony and the orchestra itself. It is hardly advisable to attempt a Berlioz program without elaborate resources.

One of the best estimates of Berlioz’s shortcomings may be found in the biography of W. H. Hadow, Esq., used in the Grove Dictionary. Mr. Hadow writes: “There is, indeed, a singular perversity in Berlioz’s music, due partly to a twist in his disposition, partly to deficiency of early training. He had, for example, a spring of pure and beautiful melody, and in La Captive in the love scene from Romeo, in the great septet from Les Troyens, he showed that he could employ it to noble purpose. Yet, time after time he ruins his cause by subordinating beauty to emphasis, and is so anxious to impress that he forgets how to charm. The Evening Song in Faust is spoiled by the very cadences that were intended to make it effective. The beginning of the Pilgrim’s March in Harold is delightful, but the last strain offends like a misplaced epigram. No doubt there are other artists who have yielded to similar temptation. Chopin used often to end his dreamiest improvisations with an unexpected discord. Heine often closes with a freakish jest, a song full of pathos or romance. But these men did it out of sheer mischief. Berlioz did it because it seemed to him the natural outcome of his thought.

TEST QUESTIONS.

1. State the nature of the French Government during the early years of Berlioz’s life.

2. What assistance did Berlioz receive from his family?

3. What instruments did Berlioz play?

4. Who was Berlioz’s principal teacher?

5. How long was Berlioz at the Conservatoire?

6. Tell something of Berlioz’s romantic marriage.

7. Describe Berlioz’s remarkable productivity.

8. How did France recognize Berlioz.

9. State Berlioz’s rank as a conductor and as a composer.

10. Why is it impracticable to give short programs of his compositions apart from the orchestra?