By the Distinguished Piano Virtuoso and Intimate Friend of Liszt

By the Distinguished Piano Virtuoso and Intimate Friend of Liszt

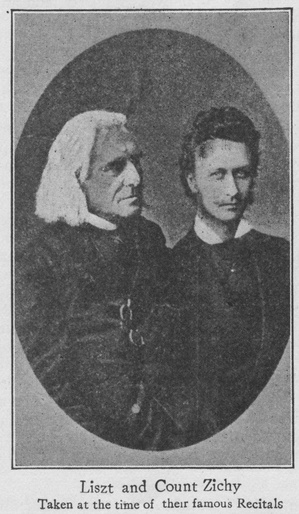

COUNT GÈZA ZICHY

Ex-President of the Hungarian National Academy

[Count Geza Zichy was born July 22, 1849, at Sztàra, Hungary. He lost his right arm when he was seventeen years old, but was so devoted to music and to piano playing that he continued his musical work, under Volkman, Mayrberger, and finally with the great Liszt. Although an able jurist and the holder of many eminent positions in the Hungarian Government, he has also had time to give, as well as supervise, concerts for charity. He has been president of the Hungarian National Academy and Intendant of the Royal Opera House, at Pesth. In addition to many pieces for the left hand, cantata, etc., Count Zichy has written two operas. He was one of Liszt’s most intimate friends, and in his home land the name of Count Zichy is inseparably connected with his famous teacher. The following extracts are taken from Count Zichy’s recently published volume, Aus Meinen Leben, parts of which have appeared in the Allgemeinemnsik Zeitung.]

LISZT’S GREAT BREADTH.

“Liszt was a mighty organ, in which hundreds and hundreds of different registrations were represented. In every register that one might try one might hear sound from a new world.

“There have been many disputes over Liszt’s real nationality. Liszt was in heart a Hungarian; in his love of German music, he was a German; in his social relations and culture, he was French; from the aristocratic and conservative standpoint, he was French, and from the standpoint of plastic art, Liszt was Italian. He was, indeed, all that it is possible for a man to be.

“With the passing of the time, the image of Liszt grows continually greater. While he was with us upon earth, we were constantly called upon to wonder at his achievements, but now that he is gone, we stand astounded at his accomplishments. Moreover, we are amazed at compositions, which very few people know intimately, and which very few can play, and which very few people will ever play. Notwithstanding this, if any one were to ask me what I considered Liszt’s greatest work, I would not hesitate to say that it did not lie in his accomplishments as a virtuoso in his extraordinary compositions, or in his genial success as a conductor, but rather in the loftiness and grandeur of his soul. This was the soul that inspired and ennobled all who came within the magic circle. Liszt was never paltry or ordinary. His greatest virtues were his forbearance and a beneficence, which at times was almost Apostolic.

LISZT AND THE HUNGARIAN FOLKSONG.

“The source of Hungarian music is found principally in the Volkslied, the song of the people. The spring does not flow as freely as in former times, but it has by no means stopped. New songs continually appear, whether of gypsy origin, or whether from people with some schooling.

“The Hungarian folksongs are richly endowed with beauties of form, rhythm, melody and infinite variety. Liszt knew the Hungarian folksong with all its merits and all its shortcomings. He would take an asthmatic little theme of eight or twelve measures, ofttimes less, develop it to a lengthy form, giving it harmonic beauty, musical content,—yes, and even raising it to symphonic heights in his rhapsodies. With the introduction of the melody, we often find it in its original form, accompanied by the simplest harmonies, but in a few moments the magic art of Franz Liszt commences. The motif is made larger, then smaller, then treated polyphonically, then decorated with all the riches of harmony, and before we know it, we find our innocent little peasant maid decked out in the gown and the purple mantle of a king’s daughter.

“The melody in many Hungarian songs often stands in direct contradiction to the words, probably because the text is often written by another person. I repeat, that the folksong is the basis of Hungarian musical art. This folksong, however, is very old. Bishop Gerhard tells of a Hungarian maiden, one thousand years ago, who sat at the spring and sang wonderfully beautiful songs.

“The early music of the church often came from the folksong. The troubadour took the folksong as his model, and it was elevated from the courts of the people to the courts of kings. Finally our Hungarian folksongs were ingeniously appropriated and orchestrated by the gypsies, although they did not create them. Of course there have been some gypsies who have composed in the Hungarian manner. Nevertheless, the gypsies did not create the real Hungarian music, nor did they bring it from Egypt with them, as some suppose. The gypsies found the music here when they came.

A THREE-HANDED PIECE FOR PIANO.

“When the city of Szegedin was visited by an earthquake, in 1879, Liszt and I undertook to give a concert for the benefit of the sufferers. Liszt came to my room and said, ‘Grieving does nothing at a time like this. We must help at once. We must give a concert for the sufferers. Come to the piano.’ We sat at the keyboard and played an arrangement of the Rakoczy March, which I had made for three hands. Then we arranged the entire program. In a few hours the concert was placarded upon all the street corners, and before night the entire house was sold out.

“As Liszt had not appeared in the city (Kalusenburg), for thirty-three years, the event took on the nature of a public festival. The stage was turned into a flower garden. When Liszt entered, the entire audience arose after the manner in which a king is greeted. Deeply absorbed, Liszt sat at the keyboard, threw back his head, glanced dreamily upwards, and played as though profoundly impressed with the transitoriness of all things, played as no mother’s son had ever heard a man play before. In the end, his hands fell upon the soul of the instrument, as a mighty sea dashes upon the rocks of the shore. He sang of human courage and independence, of battle and victory, of exultation and transfiguration.

“Only a very few understood what he was playing, but all comprehended to the depths of their hearts the significance of his emotion. At the end of the concert, we played the Rakoczy March for three hands. I had difficulty in playing the bass loud enough with one hand to balance his ten mighty fingers. The enthusiasm was elemental. Students jumped upon the platform and carried the old master away upon their shoulders.

LISZT’S IMPROVISATION.

“A short time after this, Liszt, then seventy years old, gave another concert in Vienna, for the help of the victims at Szegedin. My famous master was in exalted spirits, and played with his enchanting charm as usual. However, when we came to play the Rakoczy March he frightened me terribly.

“In the middle section he commenced to improvise. He threw his head back and went from key to key in his own peculiar fashion. I blinked in amazement, but he only laughed at my distress and continued playing. ‘What can I do?’ thought I. When one plays with Liszt, and does not keep his place, Liszt could not possibly be blamed for the error. Consequently, I commenced to run up and down the scale with chromatic octaves, waiting for my turn to come in when Liszt resumed the actual music of the march. Fortunately, my improvisation fitted well with that of Liszt, and he whispered to me, ‘Geza, Bravo.’

AN IMPRESSION OF RICHARD WAGNER.

“During the time of the early performances of Wagner’s Parsifal, I went to Bayreuth, to hear the music drama and also to meet Wagner. Upon my first visit to Wahnfried I saw Wagner sitting under a palm, surrounded by a group of fascinating and much bepowdered ladies, who took upon themselves to fan the master with their marabou fans.

“I stood by Liszt in the salon and bade him introduce me. He, however, laid his finger upon his lips and whispered, ‘We must wait until he has finished talking.’ I have seen Liszt stand in the presence of Emperors and Kings, but never so submissively as before his father-in-law. Liszt bowed his beautiful and noble head, and taking me by the hand, led me to Wagner.

“‘Dear Richard,’ he said, in very humble tones, ‘I introduce my best friend and famous pupil, Count Geza Zichy.’

“Wagner nodded his head and I went at once to the lady of the house, whom, of course, I had known before.

“This gave me an opportunity to view Wagner’s remarkable head close at hand. His features looked as though they had been chiseled in marble. Superhuman energy and a god-like intrepidity shone from his face. His countenance seemed to threaten and his mouth seemed to say, ‘You must acknowledge my supremacy, you must bow before me, you must extol my art, and if you do not, I will cast you to the winds.’”

“No one could ever forget that head. If there is any basis of comparison at all, Wagner’s head can be compared only with that of Napoleon the Great. His manners were not those of the man of the world. (Seine Umgangsformem warren andere als die eines Weltmannes, was ja sehr begreiflich ist.) He was either persecuted or adored. Between these two extremes his life dangled to and fro.”

Count Zichy’s interest in Liszt was manifested in many ways after the death of the master. At all meetings, in celebration of the birth or death of Liszt, he easily became a central figure. His position in Hungarian musical life has been used to forward education in the highest sense of the term. He regarded the carrying out of various ideas transmitted to him by Liszt, as a kind of sacred trust.