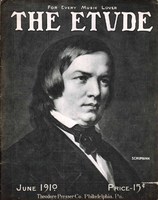

The musical world is stopping for a little while to pay its homage to Robert Schumann. It seems odd to think that had Robert Schumann lived to the age of one hundred years he would have heard musical works beside which his own compositions—derided as they were in their day for their cacophony—would sound very simple and understandable. It also seems remarkable to note that of all the composers who lived and developed the better part of their work in the early years of the last century, Schumann to-day seems the most modern and the most individual.

Chopin will never grow old. His work is distinctive, and although at times as delicate as the exquisite marking of the colors on the petals of an orchid, it is at other times powerful as the giant forest kings that stand firm and staunch against the cyclone. Wagner, tempestuous, uncontrollable, massive and all-powerful, was immortal from the day that Lohengrin was produced. Mendelssohn, Weber, Beethoven are so clothed in the mantle of classicism that many of their works have already the atmosphere of a past era, an atmosphere which in some respects enhances their interest and effectiveness.

With Schumann, however, there still remains a kind of modernism that even Strauss, Debussy and Reger have not excelled. The daring and originality continually found in his works keep him in the class with the iconoclasts of to-day. This is not so noticeable in his songs as it is in his piano pieces and in his orchestral works. He was the composer who thought not as Brahms thought—continually fettered by tradition and form; not as Wagner thought—forever incited by revolution; not as Chopin thought— turning his days and nights into beautiful tonal dreams; but as Schumann thought—considering solely the really beautiful in art and life, and following his own ideas and tendencies rather than those traditions which others had laid down.

Schumann's cutivated (sic) love for the beautiful started with his acquaintance with Thibaut, the Heidelberg professor who sought to discover the charm of music rather than to unearth the decaying technical skeletons of the tonal art. These impulses led Schumann to live the life beautiful, and when he married Clara Wieck, in 1840, he was brought into a higher and nobler appreciation of the mission of the art worker.

This wonderful romance, as remarkable in its way as that of Abelard and Heloise, or that of Robert and Elizabeth Browning, meant much for the world of music. Most of Schumann's greater work was done during the six years following this marriage. Those who doubt the genuineness of true love should read the correspondence between Schumann and his wife. Their letters atone for all the misdeeds of those whose social offenses have brought shame to music.

We shall not lead you in funeral cortege to place a wreath of tribute upon the grave of Robert Schumann, for Schumann is not dead. Have you not heard him talking to you through the Kinderscenen, the Novelettes, Papillons, Grillen, Träumerei, Warum, Traumwirren, Slumber Song, and other pieces, right in your own home. We do, however, make the suggestion that each one of our thousands of readers celebrate this important anniversary by studying and memorizing at least one of the master works of this great man in commemoration of the rich and bounteous musical gifts he bequeathed to mankind.