How Some Very Remarkable Children Have Afterwards Become Great Musicians and How Others Have Been Injured by Excessive Work in Their Childhood

By LOUIS C. ELSON

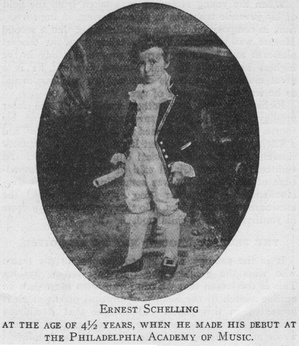

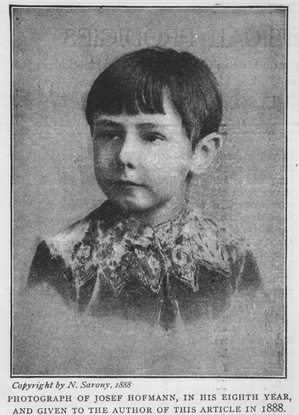

[Editor’s Note.—The place of the prodigy in musical history is not so important as many people imagine. In a recent issue of The Etude (December, 1908), Mrs. Bloomfield Zeisler speaks in very strong terms against the custom of exploiting young and talented children and causing them to make extensive and exhausting concert tours at an age when every effort should he made to conserve their health and strength for the real musical work of after years. In some instance the prodigy survives the strain of the excessive work of their childhood and becomes famous in his after years as have the two well known pianists Josef Hoffman and Ernest Schelling. Mr. Schelling has stated that he believes that his career as a prodigy was injurious in the extreme and came very near making his later work impossible. His first appearance was as a child of four at the Philadelphia Academy of Music and thereafter for several years he played continually in this country and Europe until his health was wrecked. It has been commonly stated that Josef Hoffman was upon the point of a similar breakdown when wise musical advisors insisted upon a long rest. Probably the most famous of all prodigies was Carl Filtsch. The boy was a Hungarian and a pupil of Chopin. He was so wonderful that all contemporary critics who heard him were amazed. Of him Liszt is quoted as saying, “When he starts playing I will shut up my shop.” Owing to overwork and excessive study the boy contracted tuberculosis and died at the age of fifteen. Many similar examples could be given and all point to the danger that almost invariably attends the exploiting of the prodigy. Mr. Elson writes upon the subject with his customary insight grasp and ability and the article is one which all thoughtful teachers and students should preserve.]

Away back in the tenth century there existed, at the court of Charles the Bold, king of France, a pipe-organ. It was a very different instrument from the church organ of to-day. Its keyboard did not extend to two octaves, and each key was about five inches broad and six or seven inches long. Each key had to be pressed down about a dozen inches before the pipe would speak. The player pushed it down with his clenched fist. Yet this cumbrous organ was played with considerable effect by a youngster of nine years old, whose fingering, or rather “fisting,” was the wonder of the court. This is the earliest “musical prodigy” of which there is any historical record.

Away back in the tenth century there existed, at the court of Charles the Bold, king of France, a pipe-organ. It was a very different instrument from the church organ of to-day. Its keyboard did not extend to two octaves, and each key was about five inches broad and six or seven inches long. Each key had to be pressed down about a dozen inches before the pipe would speak. The player pushed it down with his clenched fist. Yet this cumbrous organ was played with considerable effect by a youngster of nine years old, whose fingering, or rather “fisting,” was the wonder of the court. This is the earliest “musical prodigy” of which there is any historical record.

Since that time, however, there has been a long procession of precocious juveniles who have astounded the world with their early musical efforts. In this connection, it is interesting to pass rapidly in review the childhood of some of the great composers. Not all of them developed early; some of them were by no means musical prodigies. Schumann and Wagner, for example, were more prominent in early literary endeavors than in musical production.

Bach was thoroughly musical in his childhood, yet not phenomenal, for his brother, a good organist, was obliged to withhold certain advanced compositions from him in his younger years. The keen desire of the lad to play them led him to surreptitiously copy them by moonlight, for he had not a candle in his room, and thus lay the foundation for subsequent blindness. A good proof of ambition, although conveying the suggestion that Bach was not a “prodigy.” The brother has been roundly abused by most musical historians, but probably was judicious enough in his action.

Handel, although much is made of his studying the spinet in secret, and of his astonishing the Duke of Saxe-Weissenfels by his playing at seven years of age, does not enter the ranks of actual prodigies.

THE MOST REMARKABLE PRODIGY.

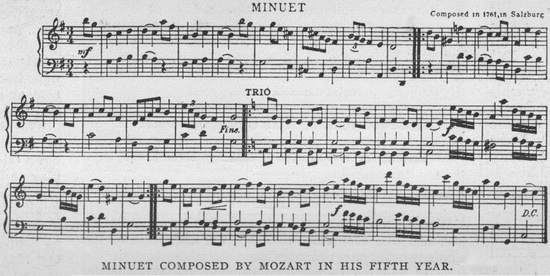

Mozart, however, has always been considered the most remarkable of early geniuses. From his very infancy he was either attracted or repelled by musical sounds. He loved the spinet and when a mere babe sought to strike consonances upon it. The trumpet, on the other hand, filled him with terror, and he ran away screaming with fright if it was sounded in his presence during his childhood. Probably Mozart was the youngest of all composers, for he created his first composition when he was but five years old. The above was this earliest work.

He had played spinet music even when he was four years of age. The concert tours which he made in his childhood are well known to all students of musical history.

Haydn was not a wonder-child although he might have been had he not been so shamefully neglected by his music teacher—George Reuter. Although Beethoven composed a fairly good two-voiced fugue when he was eleven years old he cannot be ranked as an infant phenomenon. The early development of Mozart had a decided effect in making Beethoven’s childhood unhappy, for his dissipated father had read, with envy and avarice, the accounts of the golden harvest reaped by Leopold Mozart in his concert tours with the young Mozart and his sister, Maria Anna, and determined to turn his son into a similar money-getter. The consequence was that there was furious instruction, but of a desultory sort, and it is a marvel that the young lad was not driven into a hatred for music by the injudicious means employed to force him into early development. Visitors of the family have left graphic accounts of the young Beethoven (a child of five or six years) sitting in tears at the keyboard of the spinet. But no amount of spurring could force this healthy genius to a premature ripening.

Schubert is probably the composer who brings us nearest the fount of absolute inspiration. While Beethoven revised and altered, and changed and improved his original thoughts, Schubert almost always rushed his first draft of his ideas to his publisher, without change. He was the nearest to what is called “a natural musician” that can be found among the great masters. Yet it may give food for thought when we find that even he was not a child prodigy. He wrote wonderfully in his youth, but his childhood, while it showed much intuition in musical study, was not of a character to astonish the world.

LISZT’S YOUTHFUL ATTAINMENTS.

Franz Liszt may be accorded a high rank in the list of prodigies. That he was able to astonish Beethoven (who detested prodigies) by his piano performance as a child proves very much, although the frequently-told tale of the master giving the child a kiss and predicting that he would grow up to make the world understand Beethoven is very apocryphal. Certain it is that Liszt at thirteen years of age was able to astound Paris and went from conquest to conquest from that early beginning.

It has been recently discovered that Chopin composed a polonaise at nine years of age. The work, however, shows no very remarkable signs of genius, and it may be remembered that in his days of younger childhood Chopin had a dislike for the piano.

Mendelssohn was not a child prodigy, although he was certainly a musical wonder in his youth. There is no composer in the entire list of great tone masters who at the age of seventeen produced such masterpieces as Mendelssohn’s Octette for strings, or his “Midsummer-Night’s Dream” overture. One can cite many works composed by the great masters in their youth, but never a well-rounded composition that overtops or equals their later endeavors, as was done in the case of these two Mendelssohnian numbers.

Ambition over-vaulting itself is sometimes found in the childhood of the great masters. The child Dvorak writing a polka for orchestra, before studying instrumentation, is a case in point. The result was that the brasses, not playing in the written key, caused the work to sound in two different keys at the same time. The discord may be imagined.

FEW GREAT MUSICIANS PRODIGIES.

Studying the above list carefully, we find that, with the exception of Liszt and Mozart, the tenderest childhood of the masters of music has not generally been phenomenal. A love of music has been present (sometimes not even that) and sometimes a degree of ambition, but it was in the years of adolescence that the real worth of the musical gift began to reveal itself.

Sometimes, indeed, the greatest triumphs and masterpieces were reserved for old age. Haydn’s best symphonies came after sixty, Handel’s great oratorios after fifty, Verdi’s chief masterpieces still later. A musical refutation of the dictum of Doctor Osler.

It may be noticed also with musical prodigies that sometimes the early promise was not entirely kept. Mendelssohn at seventeen was greater than any master had been at that age; but Mendelssohn at thirty-five was not the equal of the great tonal masters at the same epoch of life.

The promise of very early development is far more often broken. Everyone who has been closely connected with our art for any length of time may recall instances of children of wonderful musical attainments, who became only routine musicians in later years. Maurice Dengremont burst upon the violin world, years ago, as a star of the first magnitude—a child wonder. But he grew smaller as he grew larger and finally his skill at billiards overtopped his brilliancy as a musician.

Brahms, whose entire career was the reverse of a child prodigy, is a good example of what we mean. It was not a bit less wonderful for him, a youth, to transpose the piano part of the Kreutzer Sonata (accompanying Remenyi) from memory, or to bring noble sonatas which sounded like “veiled symphonies” to Schumann, than it would have been to have excited a gaping public by imitating great things without understanding them, ten years earlier.

THE NEW PRODIGY.

It will be noticed also that the tendency to-day is to avoid startling exhibitions of precocity. There is always a great temptation to exhibit a wonder-child, but that exhibition almost always works harm to the true development of the highest artistic ideal. The best teachers to-day hold back their pupils until they are artists—which no child can entirely be. Among the musical wonders of the present we find a Mischa Elman, of seventeen years of age, a Germaine Arnaud, of the same age, but the young phenomenon who has to be lifted upon the piano stool and whose feet cannot reach the pedals, is fortunately absent. This is a far more normal state of things. A youth who has been carefully trained from childhood, in music, who has avoided the conceit which often comes from premature public triumphs, may be a well-poised artist at seventeen or eighteen.

It will be noticed also that the tendency to-day is to avoid startling exhibitions of precocity. There is always a great temptation to exhibit a wonder-child, but that exhibition almost always works harm to the true development of the highest artistic ideal. The best teachers to-day hold back their pupils until they are artists—which no child can entirely be. Among the musical wonders of the present we find a Mischa Elman, of seventeen years of age, a Germaine Arnaud, of the same age, but the young phenomenon who has to be lifted upon the piano stool and whose feet cannot reach the pedals, is fortunately absent. This is a far more normal state of things. A youth who has been carefully trained from childhood, in music, who has avoided the conceit which often comes from premature public triumphs, may be a well-poised artist at seventeen or eighteen.

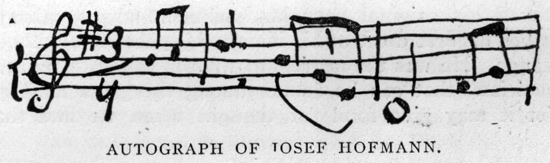

When the young Hofmann was taken from the field of his juvenile triumphs in piano-playing, in improvisation, in composition, all the world thought that a second Mozart was to come. He was taken from the concert platform and began an earnest course of study in the highest branches. He has became famous; he is a great musician; but he is certainly not as phenomenal as he was at eight years of age.

Richard Strauss is another example of the later prodigy. He had, to be sure, played piano from his fourth year, he had composed a “Schneider Polka” and a Christmas song at six, but he went steadily on, until sixteen, with a solid classical education in music. At eighteen Professor Giehrl said of him that his knowledge of musical forms was something “gerade zu Verblueffendes”—“altogether too staggering”—for the musicians who knew him. So that his prodigyship came in youth and not in childhood.

THE PRODIGY SHOULD NOT BE EXPLOITED.

It is the prodigy who is kept longest in the traces who wins the greatest and the most lasting results. This is the lesson that we can glean from even such an outline sketch of the history of musical prodigies as is presented in this paper. The fugue that Beethoven wrote at eleven, the quartette for strings that Strauss wrote at seventeen, the fughettas that Weber published when he was under twelve years of age, are landmarks in the development of the suppressed prodigy into a real master.

The public will always shower its wildest enthusiasm upon the abnormal; an almost impossible high note from the throat of a soprano or a tenor, a series of superhuman skips upon the violin, a display of unexpected virtuosity from a child-pianist, will always create a greater furore than a musicianly and masterly performance or composition by a “grownup.” Time, however, takes its revenge; the phenomenon lasts but for a little while, but the artist stays permanently; the astonishment diminishes by degrees, the more earnest revelation grows continually. The twentieth century seems to be emancipating itself from the reign of the juvenile prodigy, not so much because of a change of public heart as because of increased wisdom on the part of parents and teachers.

It may be fitting to end this sketch with a few words as regards the tests to determine the presence of a truly musical nature in the very young. It is not in the mere loving of tunes, for that fondness for melody is more widely spread about than many imagine. Every peasant child in Hungary and Bohemia has it, every Gypsy infant seems to exhibit it, and many children in all nations possess this much of musical faculty.

Even absolute pitch does not mean as much in this connection as many suppose, for the present writer has found this sure identification of tones (a species of musical memory) absent from some highly gifted musical natures and present in some musical mediocrities.

It is rather in the preference of harmony to simple melody; in the enjoyment of a contrapuntal structure; in the appreciation of the effects of dissonance in a musical work; it is in tests such as these that the very young Musician must be sought. And when he is found let all thought of display, public or private, be put out of sight. Train the divine gift until the intellect side of the nature has caught up with the emotional and then give to the world, not a child prodigy, but a worker and a master in the field of true art.