The Oldest Institution of Musical Learning in Russia

BY A. PUSIREWSKI

[We are glad to be able to include in this issue of The Etude an authoritative account of the famous Conservatory of St. Petersburg, which is the center of Russian musical education and activity, and has graduated a number of composers and artists of high rank. Mr. Pusirewski is one of the head teachers in the conservatory, and prepared for The Etude an extensive account, which was translated and edited by Mr. Constantin von Sternberg, of Philadelphia, himself a native of Russia and a personal friend of the leading Russian musicians and teachers. —Editor.]

Until the fifties of the nineteenth century musical life in Russia was in a very sad condition. Music was regarded as insignificant; as a mere diversion for the privileged classes, while the intelligent public, when not in trade, considered solely the military or official career as worthy of pursuit. To study music seriously and professionally was considered improper. Though the higher circles of society were musical in a sense, their music-making was but poor dilettanteism. Instruction was given by foreigners, private teachers, or home tutors, who were, however, well paid.

All musical interests centered exclusively in the Opera. St. Petersburg maintained an excellent Italian opera and in later years also a Russian opera, which were very poorly provided for and supported. Hence there could not be awakened any interest in composers and their works. The singer, the songstress, and their vocal virtuosity usurped and absorbed all there was of musical interest. It should be mentioned, however, that there was no vocal celebrity in those times that was not heard in St. Petersburg. To the middle classes and the people at large the admission prices were so high as to be prohibitive, and nothing else was offered to them.

Under such conditions the establishment of a musical academy could not be thought of. There was simply no musical endeavor of a serious nature whatever, except the “Philharmonic Society” (founded, 1802) which gave annually two or three concerts for the benefit of the widows and orphans.

The programs were good, but made up mostly of oratorios.

Of schools of music, there was only the “Theater School,” where music was taught, but only in the poorest, most superficial manner. There was also the “Imperial Choir;” where pupils were trained solely for church singing, and practically only for that Imperial Choir.

It was in the early thirties that a few elect spirits turned their attention to a dissemination of serious music, and that it was thought necessary to cultivate the musical taste of the public at large. For there was an abundance of talent, but it was only the few who could afford to go abroad to study; the great majority who lacked the means need opportunity to study at home.

It was in the early thirties that a few elect spirits turned their attention to a dissemination of serious music, and that it was thought necessary to cultivate the musical taste of the public at large. For there was an abundance of talent, but it was only the few who could afford to go abroad to study; the great majority who lacked the means need opportunity to study at home.

A. Lwoff, an amateur violinist and conductor of the Imperial Choir, also the author of the Russian national anthem, made some strenuous and praiseworthy efforts in this direction, but failed. He asked for financial support from the crown (which is distinct from the emperor), but he had to deal with ministers of state and other high officials, who ridiculed his “visionary” project out of existence.

At the end of the fifties young Rubinstein (Anton) returned from his studies abroad, bringing a great reputation with him and established himself in St. Petersburg. This energetic, strong individuality soon attracted a number of music lovers, who were ready to aid him in his idea to educate the public through regular symphony concerts and chamber- music soirées. With their assistance he founded the “Russian Musical Society,” which was intended as a stepping stone toward the establishment of music schools in all the larger cities of Russia. From these schools he expected the training of able composers, concert artists, orchestra players, teachers, and singers.

The political and financial conditions of the times did not look promising for any aid from the crown. Hence the necessary funds had to be raised through private donations. Moreover, the government did not look with favor upon the founding of any “societies” and withheld the legally required consent. But the founder, nothing daunted, picked up the statutes of the “Philharmonic Society,” which existed only nominally, having practically ceased its activities, and pretended merely to revive it.

Now, according to the bylaws, the sole purpose of this society was to give amateurs an opportunity to practice orchestra playing at sight. Well, the playing used to be what might be expected. Under the pretext of making a few changes Rubinstein and his friends created new by-laws, and obtained the government license for the society with the new name: “Russian Musical Society.” In 1859 he conducted the first ten symphony concerts, and arranged a series of chamber-music soirées. In five years the society founded branches in Moscow (1860), Kiev (1863), and Charkov (1864), with the same programs, the same aims in view. Upon being petitioned, the enlightened and influential Grand Duchess Helene Pawlowna assumed the protectorate of the society. She was also the special friend and protectress of Anton Rubinstein.

From this time on began the serious efforts to create a music school in St. Petersburg. As the financial aid was not forthcoming as readily as was expected, all instruction had to be given gratuitously in order not to delay the opening of the school. Lessons were given partly in the palace of the Grand Duchess, and partly in the private homes of the teachers. Meanwhile the efforts to raise money were continued, and, thanks to the liberality of the Grand Duchess and those whom she could influence, there was collected, in two years, a capital of 13,000 rubles (about $7300). This modest fund enabled the school to rent a floor in a private house on September 8, 1862.

The organization is headed by a President. This position is and always was held by a member of the Imperial family. Then follows the Director, who supervises all the courses of study as well as the administration and finance. In business matters he is associated with a committee of five laymen. Further officers are the Inspector, the Treasurer, the Secretary, the Librarian, and the Archivist, all of whom are assisted by clerks, both masculine and feminine.

The nonmusical classes, organized for general collateral learning, and six in number, are under a special inspector. The curriculum here equals about that of our high schools and is supervised by the Ministry of Public Education. All the branch schools in other cities are, through their directors, accountable to the Director of the St. Petersburg central school.

The faculty ranks as follows: Honorary professors, professors of the first class, professors of the second class, head teachers, instructors, and candidates or aspirants. The latter must serve three years as instructors before they obtain their title as such. This title is conferred by the “Artist Council,” composed of the professors and head teachers, which council also prepares all necessary changes, rules, appointments, etc., for the Director’s approval.

Under the presidency of the Grand Duchess Helene the Emperor Alexander II gave the school an annuity of 5000 rubles and a building belonging to the crown. A little later the school was moved into still larger quarters in a part of the immense building of the Ministry of the Interior. In 1866 the Grand Duchess succeeded in obtaining from the emperor the official name of “Conservatory” for the school. She also gave each year about 10,000 rubles to it, a sum that enabled the school to begin to pay its heroic instructors.

Her successor (1873-1892) was the Grand Duke Constantin Nicolaevich. Thanks to his intercession, the imperial annuity to the conservatory was raised from 5000 to 15,000 rubles. Under his personal participation the by-laws were largely amended so as to secure to the teachers as well as to the students many of the privileges granted to government officials.

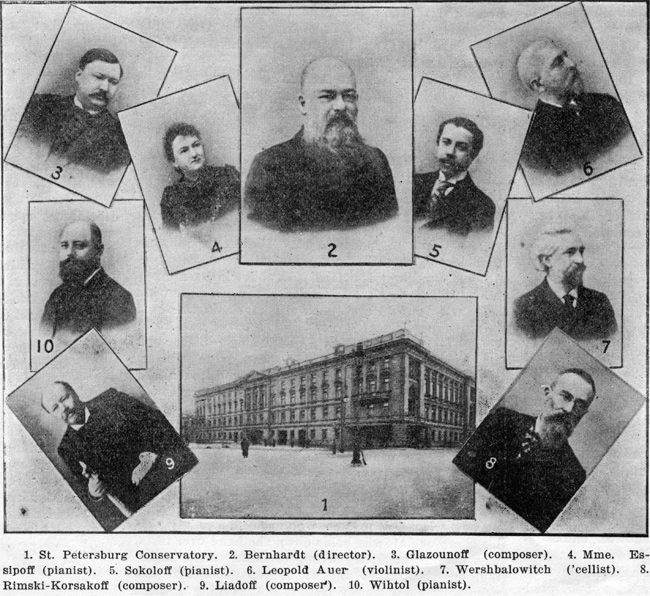

The Grand Duke was succeeded by his widow. Her Imperial Highness, Alexandra Josefowna, who obtained from the emperor the building of the Grand Theater for the use of the conservatory. The interior was completely remodeled. This 2,000,000 ruble building is in the central part of St. Petersburg, covers an immense ground, contains a large hall (with full operatic stage and large organ) seating about 2000; a smaller hall (seating 600), also with an organ; the library, distributed on two floors; the Glinka Museum, the Rubinstein Museum, a museum of antique instruments, an acoustic cabinet, a chapel, several conference rooms, recreation rooms, forty classrooms, five complete dwellings for administrative officers, and a large dormitory for the servants.

Rubinstein, the founder and first director, organized in the very first year thirty-five classes or courses, of which twenty-eight composed the professorial curriculum. The rest was auxiliary, like composition, virtuosity, orchestration. Furthermore there were obligatory studies for all students, whatever their specialty might be: Theory, History of Music, Solfeggio, and Chorus Singing. The pupils numbered 179, and the faculty showed names of world-wide repute, as we soon shall see.

The second director (1867-71) was N. I. Saremba. He developed the curriculum on the lines of his predecessor, and made the important addition of those classes in which the regular high school branches were taught.

His successor was M. P. Asantschevski (1871-76), who bequeathed to the conservatory his precious library of rare books on musical subjects, books in divers languages and of great antiquarian value.

The fourth director was the celebrated violoncellist and composer, C. I. Davidoff (1876-87). He added to the general course the classes for Orchestral Playing, Conducting, Score Playing, Opera Classes, and a special course for Musical Pedagogics. He also founded a Benevolent Society for poor students through which they could obtain decent rooms at moderate prices. In this he was ably assisted by his enthusiastic wife. His sudden death prevented the realization of his idea to eliminate from the conservatory all the lower grades of study by erecting a special building for those, in order that the conservatory proper should be devoted entirely to higher academic work.

His successor was Rubinstein, serving for the second time. He raised the standard of examinations— especially in Composition and Piano Playing—very high. He also organized an orchestra among former students of the conservatory. This orchestra gave symphony concerts at popular prices. He also thought of organizing an opera on similar principles, and with the additional advantage of giving the rising composers of operas a chance to be heard. The “Artist Council” held the times not yet ripe for such a gigantic enterprise. On February 4, 1888. Emperor Alexander III made a formal free gift of the building to the conservatory.

I. I. Johannsen, who for many years had taught Composition, Harmony, Counterpoint, and who had also acted as inspector, was the sixth director (1892-98). The present, seventh, director is the former inspector and theorist, A. R. Bernhardt.

Of the teachers, the following might deserve special mention: A. Rubinstein, A. Dreyschock, Th. Leschetizky, L. Brassin, Ad. Henselt, Sophie Menter, Henry Wieniawski, L. Auer, Mme. E. Viardot (the daughter of Garcia), Nissen-Salome, and many more of equally high repute. To these should be added those teachers who graduated from this same conservatory, and their number is very large; but a few names may suffice, such as Tschaikovsky, Glazounoff, Balakiroff, Arensky, Dlussky, Liadow, Nekrassow, Gabrilowitch, Sapellnikoff, F. Blumenfeld.

Last year the conservatory was attended by 1200 pupils, who were instructed by 80 teachers. The classes of special and auxiliary studies number 109.

Very large is the number of former pupils who are now a credit to their Alma Mater in many different occupations, namely, orchestra players in court and municipal theaters, pedagogues, concert players and composers. Space forbids to name even those only who have built up honorable positions and local reputations for themselves.