By William Armstrong

By William Armstrong

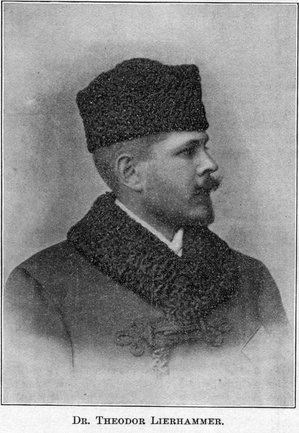

Dr. Theodor Lierhammer is an interesting personality, one who brings to his task as liedersinger an ideally complete equipment, emphasizing once more the importance to the executant musician of a broad musical education.

Of musical parentage, he is by birth a Pole, his mother being of that nationality and his father an Austrian. Of languages he is the master of six—German, Polish, Russian, Italian, French, and English; but German is the one, above all others, that he prefers to sing.

At the outset he had a scrap of a voice. Alone, he succeeded in building it up to the compass of an octave; after three months’ study with a teacher he had the beginning of two octaves. It is the mentality of the man and his genuine musical qualities that have made for his success vocally, and as an interpretent.

A graduate in medicine of the University of Vienna, later a practicing hospital physician, Dr. Lierhammer’s first serious musical study began at the age of 24. In his beginnings a pupil of Fischof, Zöllner, and Ress at the conservatory of the Kaiserstadt, he completed his apprenticeship with Stockhausen and in Paris. Making his début in a concert before the Emperor Francis Joseph he gained the interest of the Crown Princess Stephanie, whose protégé he became, until, in 1900, he took up his residence in London, where he has lately been appointed professor of singing at the Royal Academy.

Some of his tours of the British Isles have been made with Ysaye, Felix Weingartner, and more recently with Richard Strauss as an interpreter of his songs, being selected in preference to Madame Strauss de Ahna, the wife of the composer. Beyond this he has toured in Italy, France, Germany, Russia, and Austria, and more lately in the United States.

All this I knew before our talk one morning; from him I should never have gained the information, for he is too enthusiastic in talking of his art to remember to talk about himself. There is nothing startlingly unconventional in his ideas that will lead one into experimental paths; instead, he is master of the intellectual and conservative, and deals with facts that go to make the solid foundation of the liedersinger’s work.

“To me the lied is the highest level of the singer’s art,” he said at the outset. “It holds the same place in song that chamber music commands in the instrumental form. In speaking of the song one thinks instinctively of the German lied, which has so splendidly enriched musical literature. In its study we find things reversed; for, while in other branches the singer considers first that which suits his voice, in the lied the word, the poem, has prime weight in the matter of appeal.

“The poet inspires the composer. The same should be the case with the liedersinger. If the song suits him he should read the words twenty times over, pondering on them until he grasps their spirit fully and with sympathetic appreciation. Yet, perhaps nine hundred and ninety-nine in a thousand pursue the opposite course, giving the giant share of attention to the notes. The average care for the composer, but do not realize the beauty of the poet. And yet he inspired the composer, and in equal measure he should also inspire the singer. Of these two things that go to make the lied, text and music, it is impossible to do justice to the one without the other.

Vocal Demands for Lied Singing.

“In opera, first, voice production; second, effect; and, third, perhaps enunciation are required. In the lied enunciation comes first; production, second; and voice, third.

“The fact remains that a very fine voice is not so good for the lied; the eminent opera singer is rarely a good liedersinger. The greatest liedersingers of our time were not vocal giants.

“There is something so intimate about the lied that the quality of voice best for its interpretation is not of the overshadowing class, so to speak, but sympathetic and capable of varied color. By this I do not mean, of course, that the liedersinger must not have a good voice, but, necessarily, of a different type from the voice suitable for opera, where absolute beauty of the organ is the prime necessity. The smaller voice, properly trained, with attributes which go to make it an exponent in keeping with the task, and dominated by brains, carries with it the intimate character demanded by the lied. The old saying that ‘to sing means voice, voice, and more voice,’ would be, in its application to the liedersinger, absurd. In contrast with the opera, where great caliber and glaring colors are needed, the liedersinger must have infinity of subtle tone-color and command restraint in great degree.

“Alice Barbi, in spite of being an Italian, was the greatest liedersinger of the century. Her voice was not remarkable, but average. But she had the most extraordinary capacity of conveying the spirit of the lied to her audience. About her singing there was the atmosphere of poetry in the highest degree. To hear her sing Brahms’ ‘Immer Leise’ or Schumann’s ‘Frauenliebe und Leben’ was to have stamped upon one’s memory an unforgettable recollection. The greatest masters—even Brahms, who was so difficult to approach—were most enthusiastic about her singing, and accompanied her in Austria and Germany.

Color in Singing.

“A liedersinger should be like a painter; he makes his effects from the palette. It is to him indispensable to give color to the voice. This is the outcome of great study, and the basis is a good voice production. A throaty voice is quite unfit to make any success in the lied. Such a one can be dramatic in utterance and phrasing, but cannot command the vocal color which is of absolute necessity to the singer of lieder.

“It is entirely wrong to produce a lied in a tremendous hall to a tremendous audience. In opera we work with the ring of the voice; on the concert platform the lights and shades are of pre-eminent importance. On the operatic stage these subtleties of color would be drowned in the great hall and by the orchestra, but to a liedersinger the mastery of color is indispensable. The difficulty with the dramatic lied is not to bring into it the tricks of the stage; in the ‘Erl King,’ for instance, to avoid the coarseness, and yet to give an artistic and proper delivery. In this aspect the pronunciation plays a great rôle.

The Legato.

“The greatest difficulty, and one which causes hundreds to fail, is the inability to sing legato. Unfortunately, little attention is paid to it. Legato singing remains the greatest art in song. Without it one cannot sing Mozart or Schubert. And legato must be finely distinguished from slurring, which is a most reprehensible habit. The legato is something which we admire in old schools, but nowadays, unhappily, do not pay enough attention to. A paragon in this direction is Madame Marcella Sembrich.

Great Song Writers.

“In speaking of the gems of lieder literature one turns instinctively to Beethoven, Schumann, Schubert, Brahms, and Cornelius; to Hugo Wolf; and of late to Richard Strauss. The most simple lieder are the most difficult ones; and those that we deem childish and unaffected are the hardest to interpret correctly.

“Schubert wrote so well for the voice, his songs are always so vocal, which one cannot invariably say of Schumann; but, for the matter of that, neither can one say so of Beethoven. On the other hand, Schumann, the romanticist, so sound in his nature, was much more happy in the selection of his text.

“Schubert’s melody is always beautiful and simple, but most difficult to reproduce. What Mozart is to opera, that is Schubert to the lied. And as to his range, need I speak of that? Schubert had a genuine force, even a great dramatic force. His ‘Erl King’ is a tremendous drama; in ‘Haiden Röslein’ he made a charming little picture.

“Turning to the beautiful songs of Brahms, I would say: Begin your study of him with his folk songs; they are the door opening to his spirit and method. The delightful settings that he has given to them make each a little gem for the student. Their delivery is difficult, because most of the folk lieder are strophes,—the same melody for several verses,—and without care and forethought you are apt to grow monotonous. Study the words and give as much color to them as possible. That is a developing exercise.

“The acme in the lied was accomplished by Hugo Wolf. Unfortunately he is not always vocal. To the musician the songs of Wolf present an exhaustive source of study, for in almost every one of them he shows the highest art. In the selection of words he can be taken as a paragon, and with him word and tone exactly correspond. Wolf’s songs are characteristic of his gigantic temperament.

“In his songs Richard Strauss follows the same road; he has an inexhaustible store of melody. Among his contributions to this form are fine and beautiful ones, and we may expect more from him.

Keep Within Your Powers.

“A great mistake with students of the lied, a mistake shared by those engaged in other branches of art, is an ambition to perform things beyond the mechanical means at their command. Such will take up a song by Grieg without a knowledge of piano or of legato, and without an idea of style; they attain to impossible results. It is as logical as though one who would better try to play ‘Home, Sweet Home’ aspired to a Liszt rhapsody. It is a blessing, in this direction at least, that the songs of Wolf and some of those by Strauss must remain to the technically uninitiated a book of seven seals.

“Good selections to begin with in the study of the lied are to be found in the songs of von Fielitz and Lassen, which may be classed as between the ballad and the song. Later, folk songs form an admirable study; there is any amount of them, in the English, French, German—all countries furnish them. They are tuneful and good music, and will be found most instructive. The folk song should play a greater rôle—it should displace the ballad; yet it is given an inferior rank. But the folk lieder are the best pearls known.”

In talking on a subject intimate to any man, one gets a glimpse of his equipment, quite aside from any opinions that he may express on the work that absorbs him. Mr. John Drew has the most complete vocabulary of any man on the stage with whom I have talked, the outcome of a study of many rôles by well-equipped dramatists each with his special range of expression. With Dr. Lierhammer, in telling a story in general conversation, he gives it briefly, simply, yet graphically, and full of fancy—the result of study of the exact meaning of the words that he delivers in his lieder, and their relation to the picture that they sustain, conveying thus unconsciously the prime point in his art—the equal importance of the poet and the composer in the song.