REFINEMENT, fine feeling, and sympathetic appreciation are the qualities that have aided in marked degree in the success of women as song-writers, a form of musical composition for which the sex seems admirably adapted.

To those who are either entering upon the struggle or who have in a degree overcome the obstacles of a calling nothing is more cheerfully encouraging than the parallel experiences of others. This is especially the case when conditions are identical, and at those moments which come to each of us, moments in which we consider our own lot as fraught with more difficulties than that of any other.

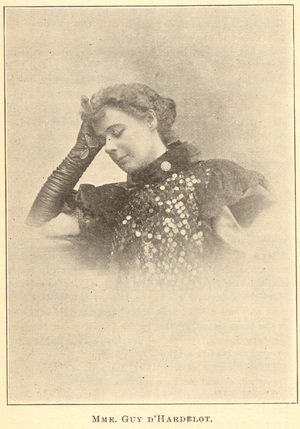

The three examples at this moment in mind,—Miss Frances Allitsen, Madame Liza Lehmann, and Madame Guy d’Hardelot,—each successful in her particular field, are each so widely different in individuality and in the matter of surroundings as to make them interesting subjects. All three have gained recognition in America.

To the acceptance in this country of Madame Lehmann’s cycle “In a Persian Garden” is directly due its popularity in England. Miss Allitsen’s largest income is received from her American publishers. As to Madame d’Hardelot, her songs are found in the portfolios of many women amateurs, and had her second visit to the United States been accomplished this season as projected, the charm of her personality would doubtless have led to a wider popularity for them.

Miss Allitsen emerged from surroundings well calculated to stifle the strongest of art instincts, and at a comparatively late day first took up the study of composition.

Madame d’Hardelot, more fortunate in the atmosphere of early surroundings, brought to her task a charm of individuality that may be ascribed in certain measure to her Irish ancestry, and a talent for dainty melody. She, too, began to study composition later than the accepted time and handicapped by many hours of daily teaching to accomplish, a handicap at one time shared by Miss Allitsen.

FRANCES ALLITSEN.

FRANCES ALLITSEN. An odd, lonely little girl, thrown upon her own resources for amusement, Frances Allitsen improvised ballads at the piano, her favorite theme being of battles, a theme strangely at variance with the Miss Allitsen of to-day, whose chief charms are her gentle voice and violet eyes. Wanting to be a singer, she began to study, only to lose her voice. Any predilections in a musical direction were frowned upon and association with musical people not to be thought of, according to the ultra and peculiar views of her family. Her girlhood was spent in a little English town where, as she puts it:

“It was impossible to go out walking of an afternoon without it being imputed that I was going to see the young men come in on the train; where the chief subject of conversation was garments, and the most extravagant excitement sandwich parties.”

With the loss of her voice Miss Allitsen began to compose and to engage a little in the writing of fiction, some of which found its way into the magazines. Domestic troubles, illness, and death put these things away from her mind for years, and it was not until a severe illness, brought about by overstrain, that Miss Allitsen a twelvemonth subsequent to her trouble turned her thoughts once again to composition.

Taking some of her manuscripts to Mr. Weist Hill, of the Guildhall School of Music in London, her talent was recognized by him, a recognition accompanied by pronounced regret that she had put off serious study until so late. Again, conditions were unfavorable, for Miss Allitsen was engaged in teaching singing, and the major part of her days being necessarily spent in trains and omnibuses, the night hours alone—and in a state of exhausted fatigue—were left for study.

Miss Allitsen acknowledges that in looking back she scarcely sees how she lived through those days, for she is very frail, but live through them she did, and besides laying the foundation for her song composition she wrote an overture for grand orchestra, “Slavonique,” played under Chevalier Zavertal and Mr. Augustus Manns, and an overture, “Undine,” which won a prize offered by the Lady Mayoress. Again, after another period of hard study, Miss Allitsen is at work on compositions for orchestra.

Being very retiring, and unable to push her work, a fresh obstacle presented itself when her earlier songs were completed. She has, though, a faculty of winning friends by her silent gentleness and these, fortunately, supplied the missing quality of “push,” and by degrees Miss Clara Butt, Mr. Hayden Coffin, Miss Esther Palliser (an American singer, a native of Philadelphia), and Miss Ada Crossley, together with some others, sang her songs into general notice. Americans Miss Allitsen regards as the quickest of people musically, and she never lets pass an opportunity for expressing her appreciation of the very material encouragement this country has given her work.

The poets from whose verses she makes in major part her selection are Swinburne, Browning, Shelley, Longfellow, Riley, and Alfred Austin, the last of whom she reckons among her close friends. Her simple little sitting room is decorated with the photographs of artists and of young girls who come to confide their love-affairs to her. Added to these are photographs of their husbands and husbands-elect. On the piano is a photograph of Lord Kitchener of Khartoum. One day, in talking to a writer, Miss Allitsen said: “Whenever I feel like shirking my duty I look at his portrait.” Judge of the composer’s surprise, a surprise naturally not unmixed with chagrin, not- withstanding the humor of it, when she read herself quoted as saying that she could not compose without a portrait of Lord Kitchener before her.

GUY D’HARDELOT.

GUY D’HARDELOT. Of mingled French, Irish, and English ancestry and of English birth, Madame Guy d’Hardelot’s early years were spent at an old chateau in Normandy. After study in Paris she went to London. Subsequent to her marriage reverses came, and she began to teach singing, studying composition when it became evident from the reception of one or two of her first efforts that she had a chance in this direction. Her success in the main she attributes to the fact that her teacher, Clarence Lucas, strove to develop her individuality by unconservative method.

Three precepts observed by Madame d’Hardelot in her work should be here quoted.

“Avoid setting familiar things. Get words in such tangible form that people see the picture. Never reach your climax until the end of the song; many a play fails because its author has lost sight of the fact that interest must increase to the end.”

French and English verses she has used almost equally for her song-settings, some of the former being by Victor Hugo, and of the latter by Ella Wheeler Wilcox. Latterly she has gone in for “acting” songs, one of which, “The Fan,” has been translated into French for Madame Calvé.

The singing of her songs by Madame Calvé has been of advantage, but far more than this has been the singing of these same songs by Madame d’Hardelot herself. Her voice is not much, but there is an individual charm about all that she does that carries things with her hearers. Again, her diction both in French and English is admirable; and upon this point she lays great stress in her teaching, which she still energetically pursues. Her home is Siddons House, in Baker Street, an old mansion once occupied by the famous actress, and now threatened with demolition to make way for an underground railway station.

Once each season Madame d’Hardelot gives an “At Home,” at which half of musical London is present.

LIZA LEHMANN.

Madame Lehmann, possessed of inherited talent from her mother, known as a song-writer and arranger under the initials A. L., has had from the outset the advantages of musical surroundings and leisure. Educated to be a concert singer, but unable to appear in public without suffering from extreme nervousness, she first turned her attention to song composition after her marriage, an occasion which marked her retirement from the concert room.

Madame Lehmann, possessed of inherited talent from her mother, known as a song-writer and arranger under the initials A. L., has had from the outset the advantages of musical surroundings and leisure. Educated to be a concert singer, but unable to appear in public without suffering from extreme nervousness, she first turned her attention to song composition after her marriage, an occasion which marked her retirement from the concert room.

Of the three, while Miss Allitsen had the most discouraging surroundings, Madame Lehmann experienced the greatest difficulty in getting into print, her “in a Persian Garden,” having literally gone the rounds of the London publishers only to be refused, being finally accepted with misgivings by a firm to which it eventually brought a tidy fortune.

Of the three, while Miss Allitsen had the most discouraging surroundings, Madame Lehmann experienced the greatest difficulty in getting into print, her “in a Persian Garden,” having literally gone the rounds of the London publishers only to be refused, being finally accepted with misgivings by a firm to which it eventually brought a tidy fortune.In a talk with Madame Liza Lehmann, known in private life as Mrs. Herbert Bedford, she told me certain phases of her musical experience that may here be aptly quoted in her own words:

“Too highly strung and nervous for a conceit career, I was glad to seize the opportunity to retire at the time of my marriage in 1894. Instead of missing the public life, I began to breathe again. I seemed to find my real life as it were. Searching around, my husband one day said to me: ‘I think a cantata might well be made out of Fitzgerald’s translation of “Omar Khayyam.”’ I studied the poem, but in the sense of a cantata it did not appeal to me. Finally I hit upon the idea of separate songs with a musical thread giving unity. The first number I wrote was:

“‘I sometimes think that never beams so red

The rose as where some buried Cæsar bled.’

“That was the first; then I wrote the whole of the rest in six weeks. But, of course, it took a long time to finish the numbers and work out the detail. I showed it to some publishers, and, by one after the other, ‘In a Persian Garden’ was refused until it had gone the round of London. They all refused it, saying that it was too difficult and that no one would sing it or play it.

“I was fearfully discouraged. I showed the composition to Mr. Ben Davies, and he was greatly pleased with it; so that, when a kind friend proposed a performance of the work at her house, the Welsh tenor assisted. The other singers were Madame Albani, Miss Hilda Wilson, and Mr. David Bispham.

“I played the accompaniments. It made an immediate success and was afterward done at the Monday Popular Concerts, when I sat in a state of nervous trepidation until it was ended; then I was called to the platform. But it was America that took up ‘In a Persian Garden.’ Prior to that it got few performances here. A prime cause for that success in America is due to the fine ensemble work of American quartet choirs because of their practice together. Here there was little interest in concerted music; singers were taken up with their solos, but now all the composers are writing song-cycles, and all the publishers want song cycles.

“I have often been asked how I compose. Of course, one must be thoroughly imbued with the spirit of words. But I am so thoroughly engrossed in my work, so absorbed, that I really do not know how a musical idea arrives; it arrives so swiftly that I can only say that it has arrived.

“If I were asked what form of composition women are best fitted to write I should say that I hope they will win in all forms. But there is this important thing to remember: we have not the muscle and strength that men have to resist fatigue. ‘We do things, but we pay the penalty of nervous strain. When people say that women are equal to men I always feel that physically they are not fitted to run the same race. If they accomplish things they pay up for it. It is sad, but it is true.”