PAGANINI’S PRISON LIFE.

To-day, as in the early half of

the nineteenth century, the widest credence is given the innumerable, fantastic

stories circulated about Paganini. His genius, his eccentricities, his mode of

life as well as his physical peculiarities,—all this was well calculated to

serve imaginative journalists with excellent material for the promulgation of

“mystery-stories,” which, however extravagant, seemed to impressionable minds

to be “just what one might expect” from such a musical phenomenon. And of all

the stories that found ready acceptance by the general reading public of

Paganini’s day, that of his imprisonment for murder seemed the most plausible

alike to his enemies as well as his admirers. Even at this distant day students

of the violin, as well as the less accurately informed general public, firmly

believe that Paganini committed a most atrocious crime for which he suffered

long imprisonment, and that, during his long and solitary confinement, he

acquired that marvelous technical skill (especially on the G-string) which

bewildered the whole musical world.

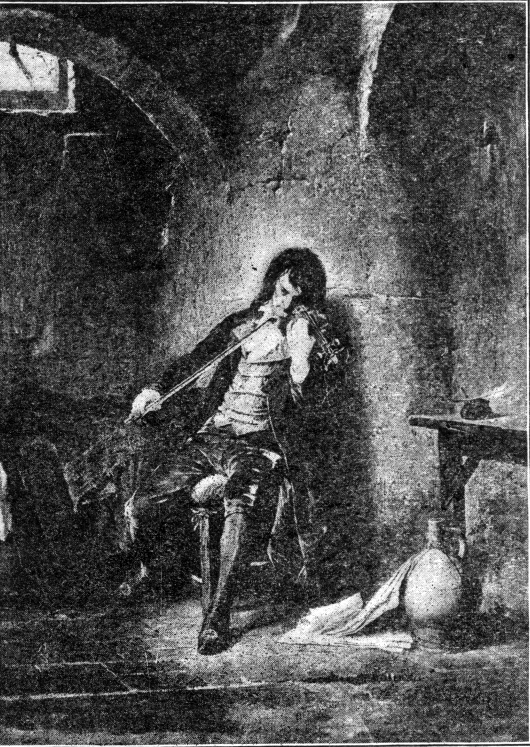

When Paganini paid his first visit to Paris, he was amazed (and

perhaps not a little pleased) to be confronted at every turn by the most

ludicrous caricatures of himself. But what particularly impressed him was a

picture representing him in his lonely cell expiating his crime at the altar of

his beloved art. This picture, it would seem, was something quite new to him;

and though, as a rule, he seems to have enjoyed the many bizarre tales

referring to his close relationship with the Evil One, he decided to offer the

excitable Parisians the true version of the prison story, together with his own

theory of the flimsy fabric from which it had been woven.

In a characteristic French letter addressed to Fetis, of the Paris

Musical Review, Paganini entered into the most interesting

details in connection with this subject, and authorized Fetis to publish this

letter literally. The following translation will doubtless prove interesting to

readers of The Etude:

Paganini’s Letter to M. Fetis.

So much kindness and applause have been lavished upon me by the

French public that I must believe that my concerts have not disappointed the

expectations aroused by the reputation which preceded me to Paris. Had I any

doubt of this, it would be dissipated by the care which I see your artists have

taken to reproduce my physical form, and also by the great number of portraits

of Paganini (whether truthful or not) which are hung on the walls of your

capital. But, sir, speculations of this kind have not been confined merely to

portraits; for, while walking yesterday on the Boulevard des Italiens, I

noticed in a print shop a lithograph representing “Paganini in Prison.” “Good,”

said I to myself, “here are honest people who, like Basile, exploit for their

profit a calumny which has pursued me for fifteen years.” Nevertheless, I

laughed as I examined this hoax with all its details furnished by an artist’s

imagination; but I soon perceived that quite a number of persons had gathered

about me, and each one, comparing my face with that of the young man

represented in the lithograph, declared that I had changed very much since my

imprisonment. I then comprehended that the thing had been taken seriously by

what you call, I believe, the mob (le badauds); and I also realized that

this speculation was not at all a bad one. It occurred to me that, since

everyone must live, I myself could furnish some anecdotes to the artists who

were so anxious to busy themselves with my affairs—anecdotes which they could

utilize for the fabrication of jokes similar to the one in question. In order

to publish these, I would beg you kindly to insert my letter in your Musical

Review.

These gentlemen have depicted me in prison; but they do not know

how I came to be there, and, in this respect, they are almost as well instructed

as myself and those who are responsible for the anecdote. There are several

stories, all equally good subjects for illustration. For example: It is said

that I killed my rival upon discovering him with my mistress. Others have said

that my jealous fury was exercised upon my mistress, but they do not agree as

to the manner of my killing her. Some will have it that I used a poignard;

others, that, wishing to enjoy her sufferings, I used poison. Each one arranged

the matter in accordance with his own fancy. The lithographers are therefore

similarly privileged.

This is what actually happened to me in

Padua, about fifteen years ago. I had given a concert which, I was led to

believe, was successful. The next day I was seated at table d’hôte; but,

being the sixtieth person present, my entrance into the dining-room had passed

unnoticed. One of the guests referred to my playing in the most flattering

terms. His neighbor joined him in these eulogies, but added: “Paganini’s skill

is not astonishing: he owes it to his eight years’ sojourn in prison where he

had only his violin to soften the sufferings of captivity. He was condemned to

this imprisonment for having assassinated, in the most cowardly manner, his

rival—one of my friends.” As may be imagined, every person present exclaimed

against the enormity of the crime. Addressing the individual who knew my

history so well, I begged him to tell me when and where this adventure had

occurred. All eyes were immediately turned toward me. Imagine the astonishment

when I was recognized as the principal actor of this tragic story. The narrator

was greatly embarrassed. It was no longer his friend who had died; he had

heard—some one had told him— he had believed—but it was possible he had been deceived—etc.

So you see, sir, how people play with an artist’s reputation, and that lazy

people will not understand that one can study just as well when at liberty in

one’s own room as under lock and key.

In Vienna a rumor still more absurd tried the credulity of enthusiasts.

I had played the variations entitled, “Le Streghe,” and they had proved quite

effective. A gentleman, described to me as having a pale complexion, a

melancholy air, and an inspired eye, stated that he could see nothing

astounding in my art, because, while I was playing the variations, he had

distinctly seen the devil near me, guiding my arm and conducting my bow. His

striking resemblance to me clearly proclaimed my origin. He was clothed in red,

and was provided with horns and a tail. You will appreciate, sir, that after

such a minute description there could be no doubt as to the truthfulness of

such a statement, and that many people were convinced that they had discovered

the secret of what they termed my “tricks of strength.”

These rumors annoyed me for a long time. I tried to prove their

utter absurdity. I called attention to the fact that, since my fourteenth year,

I had been continuously before the public; that for a period of sixteen years I

had been musical director at the court of Lucca; that, consequently, if it were

true that I had been imprisoned for eight years for having killed my mistress

or my rival, the deed must have been committed before I became known to the

public; that is to say, I must have had a mistress and a rival when I was but

seven years old. In Vienna I appealed to the Italian ambassador, who made the

declaration that he had known me for nearly twenty years as an honorable man.

Thus I succeeded in stifling this slander; but something of it has

always remained, and I was not surprised that it should reappear in this place.

What can I do about it? I see no other way than to be resigned and let

malignity exercise itself at my expense. However, I believe I ought to tell

you, in conclusion, the anecdote which has given rise to these injurious

stories.

A violinist named D., who was in Milan in 1798, became intimately

associated with two men who led a wicked life. These men persuaded him to accompany

them to the village, one night, for the purpose of murdering the rector, who was

supposed to have some money. Fortunately, the courage of one of these guilty

men failed him at the last moment and he denounced his accomplices. The police

arrested D. and his companion just as they arrived at the rector’s

house. They were sentenced to twenty years’ imprisonment; but General Menou,

after he became Governor of Milan, liberated the artist after the latter had

spent two years in prison. Would you believe, sir, that my whole history has

been embroidered on this incident? The man in question was a violinist, and his

name ended in “i”—surely that must have been Paganini! The assassination became

either that of my mistress or my rival, and it was I, so they said, who had

been thrown into prison. But, as they would have it, I discovered my new violin

school in prison. And the irons—which would have proved an impediment to my

arm—received the credit for my discovery.

Yet one word. Since impossibilities are believed, I must submit to the inevitable. The hope remains to me, however, that, after my death, Calumny will abandon her prey, and that those who have so cruelly revenged themselves for my success will leave my ashes in peace. Nicolo Paganini.