Unusual “Futurist” Harmony and Form Discussed Expressly for The Etude by the Renowned French Teacher, Composer and Organist

M. CHARLES QUEF

Successor to Alexandre Guilmant at La Trinité, Paris

[editor’s Note.—M. Charles Quef was born at Lille in the north of France, and was educated musically, at the Paris Conservatoire de Musique under Widor, Dubois and Guilmant. He has written numerous works for the organ, the orchestra, the piano and the voice. He is one of the most admired theorists in France. This article is supplemented by interesting comments from leading French composers of the day.]

French musical art has recently lost one of its most famous and most remarkable representatives, C. Debussy.

His death brings sadness to the heart of every artist; his loss will be deplored not only in French musical circles, but in those of the entire world.

C. Debussy was one of the most interesting, as well as one of the most curious artistic personalities of our epoch. To him is due the creation of a very particular style in universal musical art. By virtue of the novelty and the daring of his methods, he was an innovator who will hold a very important place in the history of music, and this because of the evolution brought about by him in musical art.

In what does this evolution—almost a revolution—consist? What is C. Debussy’s contribution to modern music? These are the points we shall endeavor to explain, by analyzing the principles of contemporary music. We shall try to set forth the genesis of this art, its texture, the causes leading to its formation, at the same time showing very impartially the advantages and disadvantages of this evolution.

What at first most strikes the hearer, is not only the great number of dissonant chords, but especially the manner in which they are linked one to the other. One has the impression of a harsh succession of chords, set together either by accident, or on purpose, to produce harsh-sounding harmonies. This impression is not at all correct. In the following pages we shall endeavor to explain how this manner of linking chords originated, and thus demonstrate the fact that it is due, not to accident but that it is the result of a very evident logic.

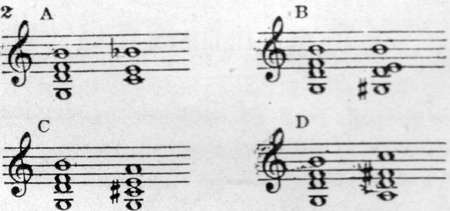

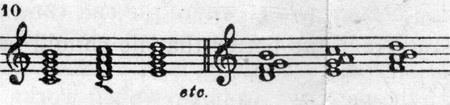

All harmonists are acquainted with this law of contemporary harmony: Any dominant seventh chord* may be linked to any other dominant seventh chord containing a flat or a sharp more or less than the first chord, as well as to any chords related to these latter-mentioned chords. Example:

may be linked thus:

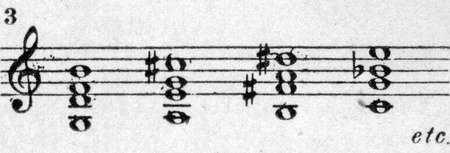

0he modern school says: Since two dominant seventh chords may be thus linked there is no reason for not linking to them a third one, then another and then another, which gives us the following succession of chords.

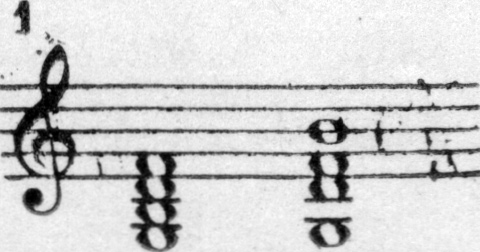

There is, furthermore, no reason for not applying the same principle to the dominant seventh chords ![]() since these two chords are related—affiliated, so to speak—being derived from the same sources, and having the same natural origin. Both are derived from the harmonics produced by the vibration of a sonorous body, a well-known principle which it is nevertheless necessary to recall here. If we cause a low G to vibrate, we obtain aliquot sounds, of which the principal are the following:

since these two chords are related—affiliated, so to speak—being derived from the same sources, and having the same natural origin. Both are derived from the harmonics produced by the vibration of a sonorous body, a well-known principle which it is nevertheless necessary to recall here. If we cause a low G to vibrate, we obtain aliquot sounds, of which the principal are the following:

Whence are developed the perfect, seventh dominant and ninth dominant chords.

These chords, as we have just observed, exist in nature, and it seems that, consciously or unconsciously, the modern school drew this conclusion:

These chords exist in nature the same as the perfect chords; their origin is the same; we shall consider them not as real dissonant chords, but as natural chords.

However this may be, and whatever may be the reason, at any event they obtained and used a succession of dominant ninth chords.

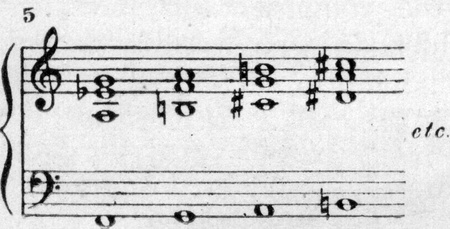

Broadening out, and by analogy, the same system was applied to:

1st. Fifth augmented chords, thus obtaining:

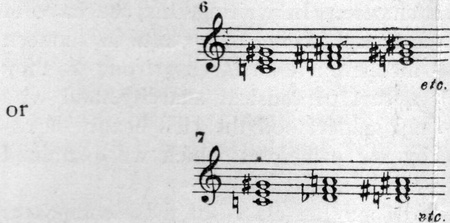

2nd: Altered dominant seventh chords:

3rd: Extended and reversed chords.

3rd: Extended and reversed chords.

Having now explained the genesis and formation, of modernist harmony, we shall leave the discussion of the subject until later. Its technic, its formation, its origin, have been analyzed with sufficient clearness to permit us to begin at once our examination of the music of this school with a view to studying its structure—its architecture, one may say.

As everyone knows, classical works, or those derived from classical modes, were built on a perfectly definite and logical plan, something on the order of a well-composed speech, and which may be formulated as follows: statement of ideas, development of ideas, re-statement of the principles which have been developed, and a peroration.

Such a plan necessarily implies a repetition of the same ideas, more or less modified. The modern school, on the contrary, says: Music is our language, our means of expression, the emanation of our thought, which we mean to express as we see fit. Why have a plan? Why submit to such and such rules of conduct; why these repetitions, why say the same thing twice? Do writers and orators repeat twice the same words, the same passages? And—at any rate—why these set repetitions at certain fixed places? Away with these rules, which often are only fetters! We would do something entirely different!

Thus were born the works of the ultra-modern school in which were applied the processes of harmony and structure of which we have just spoken, rather summarily, it is true, but with sufficient clearness to enable us to study them, or more exactly, to criticize them, and to see quite impartially their faults and their merits.

Let us examine them first from the detractor’s standpoint:

Among the detractors we find the slaves of custom and of routine; these new works disturb their exact habits, and their aesthetic sense (hitherto easily pleased), is no longer satisfied. We will pass rapidly by these detractors. At every period in the world’s history there has always existed that class of persons “behind the times” who resolutely battle against progress and refuse to admit facts and ideas which are later on universally admitted.

Leaving these detractors of modern music, let us speak of those who have quite the opposite defect. In this class we shall find certain imitators, enamored of whatever is new merely because it is new. Some of them have entirely failed to understand the modern system of harmony. They are quite unconscious of the subtle, strange and delicate beauty hidden in modern sound combinations. They understand neither the reasons for which these sounds have been brought together, nor their essential quality, the charm which springs from the very unexpectedness of their grouping. Naturally, working on a basis of this sort, they have come to think that modern music is nothing more than a suite of indiscriminate discords; these devotees of the novel have scattered dissonants everywhere, helter-skelter, without rhyme or reason, and with no beauty whatever; as a matter of fact, they have succeeded in writing a series of false notes, extremely disagreeable. And thus they risk bringing discredit on an art whose charm and subtle beauty have quite escaped them.

For this reason no reaction against such error can be too strong; no protest too violent; and all the more so as it is quite possible that these poor compositions of which we have just spoken might have been charming, had they but been sincere. In writing this, we have in view only those composers who have seen in modern music nothing but incoherent chords (as wrong as they are disagreeable), a sort of musical anarchy, and who have neither seen nor understood the rich beauty introduced into music by the principles which we examined at the beginning of this article.

Let us now speak of another class—of those composers who know and understand, who write consciously, but who make an injudicious use of these harmonic principles.

As regards harmony, the abuse of these series of chords may develop into a habit, a formula, a “trick” easy to work. And this is, very evidently, an inferiority in such art, which make it second class. It would be really all-too-easy to write a modern work if to do so it were necessary only to pile up succession after succession of discordant combinations to express insignificant or commonplace ideas. These are by no means the genuine characteristic traits of the art we are studying.

The absence in a work, of a well-established plan, develops in the composition a veritable anarchy. I remember hearing certain works where the end came as a complete surprise. Why was it there? Why not before? Why not later on? Nothing in the music showed that the end of the piece was coming. Such works have been very rightly called invertebrate. Often they are inconsistent and vague; and vagueness is perhaps the greatest fault in the conception of a work of art. The fundamental ideas, upon which the piece should be constructed, are vague, not at all clear-cut; the development of these ideas is consequently and necessarily vague. And so we have often, unfortunately, a succession of embryonic ideas, with an embryonic development; the work never comes to maturity—never has strong, clear-cut features. If one were to write a certain number of works in this style, they would logically and necessarily resemble each other.

Everyone must admit that the impressionist school has created some charming works; at the same time, however, it must be admitted that such works are the exception.

We are now at the end of the criticisms which it would have been impossible not to formulate. They are logical, and could not have been omitted, but because of them we shall be able to better appreciate the very rich and fertile contributions of Modern Art to music.

Modern music has evidently brought about a revolution in the art of composing almost comparable to the advance caused in Guido d’Arezzo’s time by the introduction of unprepared seventh chords. This theory of harmony has created—one may almost say—a new musical language, and renovated the old language by giving it a wider scope. This novel fashion of using chords, these now and unexpected combinations and linkings, have infused new life into music. Art is entering a new phase. What treasures of beauty, what unexpected—what undreamed-of resources for him who can skillfully turn them to account! It frequently happens that any other older music, if heard immediately after hearing a piece of modern music, seems flat, and almost childish. We must, however, be careful not to go to extremes, for it would be quite inadmissible to try to deny or to destroy the beautiful creations of the past. If the defective construction of which we have spoken may lead to anarchy (and certain modern works are proof of the fact) it is legitimate to hope that composers may avoid this mistake and this danger. Let us then retain of the new ideas what is best and most profitable:

1st. Liberties with harmony, in so far as the liberties do not degenerate into false notes, hideous and inadmissible. In violating rules hitherto respected, let us seek only new chords, surprisingly full of charm and beauty.

2d. Liberties in construction, which (unless they are carried so far as to produce works without back-bone, inconsistent and vague), will give them a certain airiness, with ease and freedom as well as solidity of structure.

Let us then not deliberately banish well-established themes, clearly stated and sufficiently developed, but let Art, turning to full account her new resources, wonderfully expand.

We must not neglect to mention a great improvement which is entirely due to the innovators of the modern school—the brilliancy of the modern orchestra. To be sure, older masters, and especially our great Berlioz, had pointed out the way; but the modern composers have developed the science of orchestration to a degree hitherto unknown, and have added in great profusion to the rich and glittering palette of musical painting, colors as novel as they are delicate.

M. Quef has secured the following valuable letters from leading modern French composers in corroboration of his views. The Etude has the honor to present them herewith:

“The rules of counterpoint, based upon the patient observation of laws of acoustics and the limitations of part writing cannot be allowed to lapse. The rules of harmony are in a measure based upon rules quite as strict as those of language (grammar) and they should not fall into desuetude. The bad example of composers who through ignorance or through braggadocio have declared themselves exempt is of no importance. Their cult will pass—it is a momentary affair. A school of musical art that aspired to such an end would be as incongruous as a church that boasted of mundane spheres instead of heaven as its spiritual goal.”

Paul Vidal.

“Musically I am the enemy of all that which savors of the cut and dried, whether of the old school or of the ultra modern. I am not the partisan of any school, provided the composer has a manner of his own—his individual style; that is to say, I admire the inspiration, the sincerity, the artistry of one who has something to say, and expresses it loyally with the generosity of his whole heart.”

Camille Erlanger.

“These lines do not apply in any way to those whom we have been wont to call ‘the masters of a school,’ that is to say, those who owe to their own personal gifts their incontestable fame. The others, who are incapable of dragging from their own depths anything worth while— who tow along in the wake of the real originators, in the hope of giving the illusion of being ‘someone’—of these poseurs I will say that they offer nothing that is worth taking seriously.

“Indeed, before the war it was the fashion for these ‘small fry’ to compose works of the ‘laboratory’ or ‘research’ variety, avowedly ‘scientific,’ which were without charm, sentiment, beauty, sincerity or art. This is not to imply that the laboratory method is to be despised. It has its value. But only when the material is moulded by a master hand. The laboratory can serve to forge the sonorities—the new musical expression may subjugate the imponderables—and God knows if music isn’t crammed with them! But that which is evolved should bow the knee to Life. And Life in Music is Rhythm, Melody and Harmony. The combinations and procedure come afterward. They have completely forgotten this, and it is high time that they should retrace their steps.”

Francis Casadesus.

“I do not know more than two sorts of music—good, and bad.

“There is very wholesome music among the works of the ultra-moderns; and there is also music that is truly detestable and useless, which is of a date previous.

“Bad music exasperates me—it is of no importance whether it be modern or not—for this alone is dangerous and inharmonious.”

Xavier Leroux.

*The writer assumes that Etude readers know that the dominant seventh chord is that built on the fifth degree of any scale, from root to seventh; in the key of C, for instance, the chord would be G, B, D, F. In the key of E flat it would be B flat, D. F and A flat.