Bulwarks

Who are the real bulwarks of the musical profession?

Surely not the “great” virtuosos who come and go like the tides. A few really great figures stand out permanently in the pianistic world. Enduring reputation is usually due to composition rather than to virtuoso playing. We think of Liszt and Beethoven as pianists perhaps, but they were far greater as composers, as were the pianists, Brahms and Chopin. Thalberg, Herz, Kalkbrenner and Von Bülow and others, are great in memory today because of their reputations as performers.

Who is it then, to whom the greatest credit must be given for sustaining the musical development of our country? Everyone in music has a share and every share is important, from that of the music clerk and the engraver to the prima donna and the orchestral conductor. However, the most significant and least-heralded work is unquestionably that of the music teacher about whom comparatively few people of the globe hear during a lifetime.

It is human to measure success by fame—yet fame itself is the most capricious of things. Despite all that has been written and said about them, Theodore Roosevelt, Lloyd George, “Billy” Sunday, Paderewski and Caruso are still unknown to millions of human beings on the globe. To be known and eulogized by very many people is not the greatest joy in life. Let us not judge people by their fame but by their real worth.

A teacher recently died in an Eastern music center, who was one of the thousands of music teachers of whom you have never heard. Her work was able and she was faithful to it. As her hair grew grayer and grayer her smile grew brighter and brighter. Everyone who knew her loved her and said fine things about her. When she passed away, no one seemed to mourn, because no one can mourn a beautiful sunset. She carried good music and good sense and good cheer into hundreds of homes that were better because they had secured her services.

If anyone were to ask us who were the real bulwarks of musical education in America we would point to the army of faithful, earnest, hard-working music teachers who go cheerfully about their daily tasks caring more for their mission than for the expansion of their fame and endeavoring to make music help humanity in as many ways as possible.

Music and Business

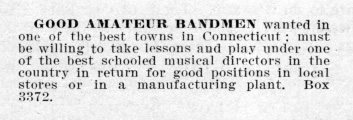

There are thousands of men holding positions in America right now who do so because they can play some instrument. Most of these men play in bands and it is not uncommon to see in some Band Magazines pages of advertisements similar to this:—

The civic pride in having a good band is so great that the musician who can “hold down” some other job has little difficulty in finding employment where the person who has no musical training might.

Music is always welcome and many a man has studied the piano as an accomplishment only to find that it has been the means of establishing a common bond between himself and an employer which has resulted in the employee receiving frequent promotions. The editor personally knows of a man who has an annual salary of $50,000 who has repeatedly said that music has been the means of gaining acquaintances who have in turn advanced him through various steps to his present position.

184,000 Golden Hours

“Whoso neglects learning in his youth, loses the past and is dead to the future.”—Euripides.

From the hour of birth until 21 years, when a man becomes of age, there is a span of 184,000 golden hours. That is the area of his youth and in that area he may build his structure in which he shall achieve his greatness or meet his failure.

Of those 184,000 fractions of eternity, it is said that only about 7,000 are spent in school—a very small contribution to so important a matter—about one-twenty-fifth of the whole glorious time of youth.

Let us say that the thorough music pupil receives two lessons a week for full eight years—a period much longer than that which the average pupil gives to music. He will then have had, at the most, 832 hours of musical instruction. As a matter of fact, many music pupils, taking one lesson a week and missing lessons by sickness and vacations, get, let us say, from 150 to 200 hours of musical instruction. With such a small fraction of youth devoted to music, both teacher and pupil should weigh every second and make it a vital one.

“Comparisons are Odious”

This pat phrase, first attributed to Miguel de Cervantes in Don Quixote, has been used so frequently by so many noted writers in so many different countries that it has become one of the universal platitudes which, by their very common currency, lose their full meaning.

One of the most unjust things that a teacher can do is to compare the work of rival pupils,—especially before the pupil. Each pupil is an individual, and it is to be assumed that the pupil is doing his level best if the teacher is doing his part. To say that Wallace plays better than Irene, although they have taken the same number of lessons, is certainly unfair to one of the pupils.

Judge each pupil’s work for its own worth. Consider the wonderful human variations in mentality which must modify the work of each individual. That is the only intelligent basis upon which the teacher can work. Why not drop the habit of comparing things and individuals?

The Etude receives an occasional letter of inquiry such as this, “Who is the greatest pianist living?” Genius can never be measured by the yardstick, and to compare Paderewski with Bauer, or Samaroff with Mero, would be like comparing an oak with a sequoia, or a palm with a willow. What good is accomplished when the comparison is completed?