At Home.

San Francisco aims to have a municipal opera house at a cost of $750,000. The prime movers in the scheme are members of the San Francisco Musical Association. $100,000 have already been subscribed.

Boston opera has been mainly supported by Eben D. Jordan, who has paid the deficits for the last three years. He is now getting tired, and has announced that he will withdraw his support unless the box-holders and a committee of guarantors agree to share the expense.

Feeling that St. Louis ought not to be musically behind other large American cities, Adolphus Busch has offered $50,000 toward the erection of an opera house, provided the remainder of the half million dollars necessary is subscribed within the next six months.

The Music Department of the city of Boston has provided for regular public organ recitals. One of these, held during the month of February at the First Church of Christ, Scientist, drew an audience of five thousand and five hundred people to hear Mr. Walter E. Young play upon the fine Hook & Hastings instrument in that church.

The Bach choir, of Bethlehem, Pa., is again under the direction of Dr. J. Fred. Wolle, formerly head of the Music Department of the University of California. The next Festival will be held May 31 and June 1 at Lehigh University. Bach’s B Minor Mass will be sung. Charles M. Schwab, the steel magnate, has given $2,500 toward the production. Many of the singers who took part in the previous festivals will participate in this one.

Die Signale, the Berlin Musical paper, published by the former music critic of the New York Staats Zeitung, August Spanuth, claims that the American daily papers give far more attention to musical criticism than the European papers. This, of course, is largely due to the fact that dimensions of American papers are usually much greater than European journals. Naturally more space can be given to music.

The Lawrence Conservatory of Music, a department of Lawrence College, at Appleton, Wisconsin, held its first Music Festival on January 1 and February 1. A chorus of 150 adults, 500 children, the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra and several soloists took part. The principal choral work was Grieg’s Olaf Trygvasson. The concerts were very successful.

At the fortieth anniversary concert of the Philadelphia Orpheus Club, held in the Academy of Music, a tablet, erected to the memory of Michael Hurley Cross, a well-known local musician, was unveiled. David Bispham and John F. Braun assisted at the concert, the chorus was augmented to 130 singers, and forty-five members of the Philadelphia Orchestra played the instrumental parts.

A memorial concert was recently given in New York on the anniversary of the birth of Julian Edwards. Mr. Edwards was an Englishman by birth, but lived the greater part of his life in this country, doing much splendid work in the aid of music. His operas, cantatas, part songs, anthems, and similar work have won for him a high place in the esteem of all who have the interests of good music at heart.

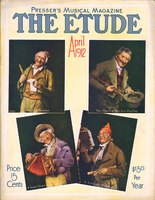

Some musicians may have an idea that the mandolin and the banjo are instruments which have fallen out of fashion. This may be true as far as the old-fashioned manner of treating them is concerned. The best teachers, however, learned that it was possible to play certain good music on these instruments, and new and larger instruments of the mandolin family have been devised. At a recent concert, given in Boston by the Festival Mandolin Orchestra, three hundred players took part.

Here is a new value for a fiddle. A barber in a little town in the middle west heard one of the young men of the town playing upon an old fiddle. Immediately the barber, who had studied the instrument in the land of song, garlic, olives and marcaroni (sic), proposed that he give his shop in trade for the fiddle. The “swap” was made. (Just here the romance stops—just at the exciting point—just where we are all wondering what the first owner of the violin did to the barber’s customers.)

Lorado Taft has been selected as the sculptor for the bust of the late William H. Sherwood, which is to be erected in Chicago. If any American musician deserves a bust Mr. Sherwood certainly did, for in addition to the value of his services as an artist he strived to give an impetus to all things

American in musical education. The Etude continually received letters from him upon this point. The subscription list will be closed in June. More money is needed right now to carry through the project, and those who desire to see a fitting memorial for this able American musician should send their contributions to Mr. Walter Spry, treasurer of the fund, 625 Fine Arts Building, Chicago.

Turning down an opportunity to make a debut in New York at an important Sunday concert, because reverence for the Sabbath was greater than the ambition to succeed at all costs seems unusual in this day and age. Yet Miss Cecile Ayres, the American pianist who has made many successful European appearances, paid a silent compliment to the faith of her fathers by refusing to make her debut on the Lord’s day. However, she did make her debut in America with the Damrosch Orchestra (New York Symphony) at the Philadelphia Academy of Music on February 24, and was greeted with an ovation after playing the difficult Grieg Concerto. Miss Ayres is a pupil of Gabrillowitsch, Safonoff, and other noted teachers. Her playing is characterized by a wholesome vigor and keen artistic intelligence. She is a daughter of the well-known educator, Dr. E. E. Ayres.

A French journal has pointed out the fact that in America the prices paid to conductors are soaring as high as those paid to great singers. Stransky has been engaged by the Philharmonic Society of New York at a salary of $25,000, and a similar amount was paid to Gustav Mahler. Karl Muck has been reengaged to conduct the Boston Symphony at a salary of $28,000, and large amounts are paid to Carl Pohlig, of Philadelphia; Frederick Stock, of the Thomas Orchestra; Stokowski, of the Cincinnati Orchestra and to other conductors. “Unfortunately,” comments our French contemporary, “the prospects of the players in the orchestras are not more brilliant than heretofore.”

Abroad.

Paderewski has retired to his home in Switzerland to devote himself to the composition of an opera.

Felix Weingartner has completed his task of rewriting Weber’s Oberon, so as to improve the libretto and rescore the opera. The new version will be heard shortly in Hamburg.

A Gustav Mahler Fund has been started in Vienna for the purpose of providing a fund for the musical education of students with talent but without the necessary means for study. The founders of the movement are the widow of Gustav Mahler, Richard Strauss, Ferruccio Busoni and Bruno Walter.

The young British composer apparently has as much difficulty in obtaining recognition as his American cousin. A young musician according to the London Star, recently asked a well-known musical wit what costume he should wear at a fancy dress ball. The answer he received was, “Go as a young British composer—for he is never recognized.”

A London magistrate recently gave some sound advice to a street singer who was brought before him on a charge of begging. “Try to improve your singing,” he said “If you sing nicely and people like it, that’s all right. If you sing badly, and they don’t like it, that’s begging.”

Mrs. Fannie Bloomfield-Zeisler has reappeared before a London audience after an absence of twelve years. Her success has been immense. No pianist has appeared in London for some time who has been accorded such an enthusiastic reception. Her success in Paris has been equally great, and Berlin has not failed to endorse the opinions of the other great European music centers.

Italian papers are commenting on the fact that Tullio Serafin, chief conductor of La Scala Opera House, Milan, has refused for patriotic reasons to accept an engagement as conductor at the Royal Opera in Vienna for three years at a greatly increased salary. The relations between Italy and Austria-Hungary have been somewhat bitter for a long time.

Interest in music increases every day. We are now informed that land tortoises have caught the popular fever. Dr. Girtanner relates that when the town band of St. Gallen began to play on the square near his garden, all his tortoises at once ran to the fence and remained motionless, with heads erect, until the end of the number.

The Musical Antiquary, an English quarterly magazine of great historical interest, contains in a recent issue an interesting article on English magazines, containing music before the early part of the nineteenth century. A glance at the pages of this journal forces one to realize that the world owes a debt to the patient scholars who dig into the past to preserve for us some relics of the art of music.

A woman’s orchestra has been formed in Berlin under the direction of Elizabeth Kuyper, a talented pupil of Max Bruch. Owing to the difficulty of obtaining ladies who play wind instruments, it has been decided to limit their public appearances to the string section of the orchestra, as there is no need for an orchestra of half men and half women in an orchestra-ridden city like Berlin. At the first concert, however, men were employed for the wind section.

Germany has been given over to gala celebrations of the two hundredth anniversary of the birthday of Frederick the Great, whose genius for statesmanship of the highest order laid the foundations of the present German Empire. Frederick the Great was fond of music, and was especially addicted to playing the flute. When he was Crown Prince he became so absorbed in practicing the instrument that he neglected his other work. Consequently his father forbade him ever to touch the flute again. Nevertheless he persevered under the able tutorship of one Quantz, an admirable flute player, who subsequently rose to great fame when his royal pupil ascended the throne. Frederick the Great composed many pieces for his favorite instrument.

Efforts which have government backing are being made in France to decentralize music. Paris is at present the musical hub of France, and the other large cities are of comparatively little artistic account. In order to combat this condition of affairs, which can only result in hindering the better development of musical art, it is now considered desirable by many to let each of the larger French cities have its own opera house and conservatory similar to those in Paris, to produce new works at the different centers, and to broaden the musical field as much as possible. The present Minister of Education, M. Guist’hau is warmly in favor of the idea.

Mascagni has followed the example of Leoncavallo and entered the London vaudeville field. It will be remembered that Leoncavallo conducted his Pagliacci at the London Hippodrome, for which he received a salary of $5,000 a week. Mascagni is conducting his Cavalleria Rusticana at the same institution, but it is said that his salary is double that of Leoncavallo. This huge stipend will doubtless console him for the fact that his new opera, Isabeau, which achieved an enormous success in South America, has been unfavorably received in Milan. Isabeau was originally to have been produced in the United States, but Mascagni proved so unmanageable, and so rapacious in his demands, that the American operatic authorities decided to get along without his marvellous new masterpiece. Mascagni made a fortune out of it in South America, where the unexpected is always happening. The opera has been ridiculed wherever else it has been produced.

Neil Forsyth, who is connected with the business side of Covent Garden opera, says that Covent Garden is the only large opera house, practically speaking, which is self-supporting. He complains, however, that the indifference of the British public to novelties places the Covent Garden authorities in a difficult position. Under these conditions the management can hardly be blamed for following a conservative course. “But when we are influenced by these conditions,” he added, “we are reproached with commercialism in art, and when we lose our money, we are told that we should have known that we would.”

A new work by Granville Bantock, the distinguished English composer, has been produced in Manchester. It is a setting for chorus and orchestra of selections from Swinburne’s Atlanta in Calydon. Professor Bantock is apparently impressed with the relation of music and color, and gave special directions for the lighting of the hall during the performance. He believes that certain tonal effects are co-related with certain color pale blue, the clarinet violet, and so forth, effects—the trumpet suggests scarlet, the flute. Whether his ideas turned out to be successful cannot be decided until the critics have done talking about it. At all events the experiment is an interesting one.

The question of copyright is always one of considerable interest, and the fact that 1913 will see an end to the copyright on the Wagner operas brings the matter into some prominence. The copyright laws seem to be in a somewhat chaotic state from an international point of view. The British government made a step in the right direction in attempting to secure an international uniform system. This effort has proved a failure, however, as other nations have not joined the movement. In Great Britain and in France copyright lasts for a period of 50 years after the composer’s death; in Germany it lasts 30 years. Consequently Great Britain and France will be protecting German music 20 years after Germany has made it free. In the United States copyright lasts for 56 years, irrespective of the length of the composer’s life.

In consequence of the actions of the French Society of Authors, Composers and Publishers of Music, many prominent artists are eliminating the French numbers from their programs. The society exacts a fee, or royalty, on the public performance of the works of its members. This is done to ensure the composer receiving a share of the profits attached to the public performance of his works. It appears to be having a contrary effect, however. Lillian Nordica once paid a fee for the privilege of singing Debussy’s Mandoline, but refuses to do so again. Maud Powell has removed the same composer’s Gollywog’s Cakewalk from her program, and other artists have followed suit. An American composer, Blair Fairchild, joined the society in 1902, but finds that it has injured his chances. He now desires to resign, but finds this impossible as the society holds his power of attorney, which is fixed at twenty years.

Some patient mathematician has counted all the notes in Meyerbeer’s Huguenots. There are 10,144 in the first act, 10,269 in the second, 13,344 in the third, 5,394 in the fourth and 3,665 in the fifth. There are also 904 other notes in a little piece written for Mme Alboni, making a grand total of 43,720. These figures serve to show something of the amount of mere writing the composer has to do in order to express his ideas in practical shape. Notes are to the composer what bricks are to the builder. How terribly ill-used the architect would feel if he had to lay his own bricks in addition to making his plans! Surely musical composition is the most laborious of arts. The painter may take his sketchbook into the fields with him and enjoy himself in Arcady with a clear conscience. The poet may, if he chooses, drink ambrosial nectar and whisper his rhapsodies into a sound-reproducing machine from a bed of violets, but the poor composer has to spend hours and hours laboriously recording his impressions on ruled paper behind closed doors.

The great organ of the principal church at Eisenach, the birthplace of Johann Sebastian Bach, which dates back to 1697, and made illustrious by being played on by many members of the Bach family, has just been replaced by a new instrument. The case only of the old original has been preserved. The new organ has seventy-five stops and pneumatic action, and its opening was recently inaugurated by a performance of Bach’s Mass in B minor.