Mme. Johanna Gadski

[Editor’s Note :—Mme. Johanna Gadski, one of the foremost Wagnerian Sopranos of our day and also one of the most successful interpreters of the “Art Songs” of Schumann, Schubert, Franz, Brahms and other masters, has given the readers of The Etude the advantage of her valuable experiences in rendering the Schumann Songs before audiences in all parts of America. Mme. Gadski has just completed a series of 56 operatic performances with the Metropolitan Company as well as 48 recitals and concerts. Her next appearance will be at the Salzberg Mozart Festival, in the birthplace of the great Austrian master.]

ROBERT SCHUMANN’S LYRIC GIFT.

One cannot delve very far into the works of Schumann without discovering that his gifts are peculiarly lyric. His melodic fecundity is all the more remarkable because of his strong originality. Even in many of his piano pieces, such as “Warum?” “Träumerei,” or the famous “Slumber Song” the lyric character is evident. Beautiful melodies which seem to lend themselves to the peculiar requirements of vocal music, crop up every now and then in all his works. This is by no means the case with many of the other great masters. In some of Beethoven’s songs for instance, one can never lose sight of the fact that they are instrumental pieces. It was Schumann’s particular privilege to be gifted with the acute sense of proportion which enabled him to estimate just what kind of an accompaniment a melody should have. Naturally some of his songs stand out far above others and in these the music lover and vocal student will notice that there is usually a beautiful artistic balance between the accompaniment and the melody.

One cannot delve very far into the works of Schumann without discovering that his gifts are peculiarly lyric. His melodic fecundity is all the more remarkable because of his strong originality. Even in many of his piano pieces, such as “Warum?” “Träumerei,” or the famous “Slumber Song” the lyric character is evident. Beautiful melodies which seem to lend themselves to the peculiar requirements of vocal music, crop up every now and then in all his works. This is by no means the case with many of the other great masters. In some of Beethoven’s songs for instance, one can never lose sight of the fact that they are instrumental pieces. It was Schumann’s particular privilege to be gifted with the acute sense of proportion which enabled him to estimate just what kind of an accompaniment a melody should have. Naturally some of his songs stand out far above others and in these the music lover and vocal student will notice that there is usually a beautiful artistic balance between the accompaniment and the melody.Another characteristic is the sense of propriety with which Schumann connected his melodies with the thought of the poems he employed. This is doubtless due to the extensive literary training he himself enjoyed. It was impossible for a man of Schumann’s life experience to apply an inappropriate melody to any given poem. With some song writers, this is by no means the case. The music of one song would fit almost any other set of words having the same poetic metre. Schumann was continually seeking after a distinctive atmosphere, and this it is which gives many of his works their lasting charm.

THE INTIMATE AND DELICATE CHARACTER OF SCHUMANN SONGS.

Most of the greater Schumann songs are of a deliciously intimate and delicate character. By this no one should infer that they are weak or spineless. Schumann was a deep student of psychology and of human life. In the majority of cases he eschewed the melodramatic. It is true that we have at least one song, “The Two Grenadiers” which is melodramatic in the extreme, but this according to the greatest judges is not Schumann at his best. It was the particular delight of Schumann to take some intense little poem and apply to it a musical setting crowded full of deep poetical meaning. Again, he liked to paint musical pastels such as “Im wunderschönen Monat Mai,” “Frühlingsnacht” and “Der Nussbaum.” These songs are redolent with the fragrance of out of doors. There is not one jarring note. The indefinable beauty and inspiration of the fields and forests have been caught by the master and imprisoned forever in this wonderful music.

“Im wunderschönen Monat Mai” which comes from the “Dichterliebe” cycle is indescribably delicate. It should be sung with great lightness and simplicity. Any effort toward a striving for effect would ruin this exquisite gem. “Frühlingsnacht” with its wonderful accompaniment, which Franz Liszt thought so remarkable that he combined the melody and the accompaniment, with but slight alterations, and made a piano piece of the whole—is a difficult song to sing properly. If the singer does not catch the effervescent character of the song as a whole the effect is lost Any “dragging” of the tones destroys the wonderful exuberance which Schumann strove to connote. The amateur singer seems to be continually trying to secure “effect” with these songs and the only result of this is affectation. If amateurs could only realize how hard the really great masters tried to avoid results that were to be secured by the cheap methods of “affectation” and “show,” they would make their singing more simple. Success in singing art songs, comes through the ability of the artist to bring out the psychic, poetical and musical meaning of the song. There is no room for cheap vocal virtuosity. The great songs bear the sacred message of the best and finest in art. They represent the conscientious devotion of their composers to their loftiest ideals.

I have mentioned three songs, which are representative, but there are numberless other songs which reveal the intimate and personal character of Schumann’s works. One popular mistake regarding these songs which is quite prevalent, is that of thinking that they can only be sung in tiny rooms and never in large auditoriums. Time and again I have achieved some of the best results I have ever secured on the concert stage with delicate intimate works sung before audiences of thousands of people. The size of the auditorium has practically nothing to do with the song. The method of delivery is everything. If the song is properly and thoughtfully delivered the audience, though it be one of thousands, will sit “quiet as mice” and listen reverently to the end. However, if one of these songs were to be sung in a flamboyant, bombastic manner by some singer infected with the idea that in order to impress a multitude of people an exaggerated style is necessary, the results would be ruinous. If overdone they are never appreciated. Art is art. Rembrandt in one of his master paintings exhibits just the right artistic balance. A copy of the same painting might become a mere daub, with a few twists of some bungling amateur’s brush. Let the young singer remember that the results that are the most difficult to get in singing the art song, are not those by which she may hope to make a sensational impression by the means of show, but those which depend first and always upon sincerity, simplicity and a deep study of the real meaning of the masterpiece.

THE LOVE INTEREST IN THE SCHUMANN SONGS.

Up to the time Schumann was thirty years of age (1840) his compositions were confined to works for the piano. These piano works include some of the very greatest and most inspired of his compositions for the instrument. In 1840 Schumann married Clara Wieck, daughter of his former pianoforte teacher. This marriage was accomplished only after the most severe opposition imaginable upon the part of the irate father-in-law, who was loath to see his daughter, whom he had trained to be one of the foremost pianists of her sex, marry an obscure composer. The effect of this opposition was to raise Schumann’s affection to the condition of a kind of fanaticism. All this made a pronounced impression upon his art and seemed to make him long for expression through the medium of his love songs. He wrote to a friend at this time “I am now writing nothing but songs great and small. I can hardly tell you how delightful it is to write for the voice, as compared with instrumental composition; and what a tumult and strife I feel within me as I sit down to it. I have brought forth quite new things in this line.” In letters to his wife he is quite as impassioned over his song writing as the following quotations indicate: “Since yesterday morning, I have written twenty-seven pages of music (something new of which I can tell you nothing more than that I have laughed and wept for joy in composing them. When I composed them my soul was within yours. Without such a bride indeed no one could write such music, once more I have composed so much that it seems almost uncanny. Alas! I cannot help it: I could sing myself to death like a nightingale.”

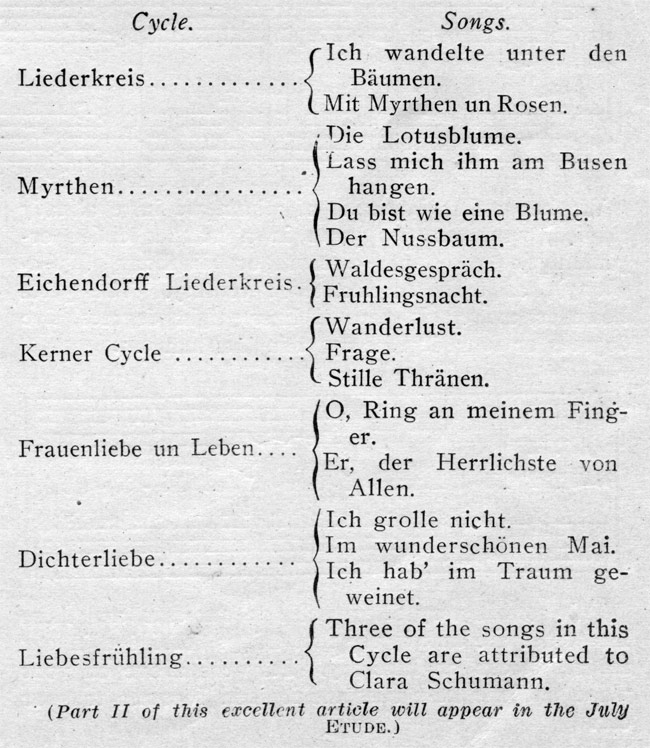

During the first year of his marriage Schumann wrote one hundred of the two hundred and forty-five songs that are attributed to him. In the published collections of his works, there are three songs attributed to Schumann which are known to be from the pen of his talented wife. As in his piano compositions Schumann avoided long pieces and preferred collections of comparatively short pieces,- such as those in the Carnaval, Kreisleriana, Papillons, so in his early works for the voice, Schumann chose to write short songs which were grouped in the form of cycles. Seven of these cycles are particularly well known. They are here given together with the best known songs from each group.