BY ALETHEA B. CRAWFORD COX AND ALICE CHAPIN.

[Editor's Note.—Some years ago Mrs. Cox completed a book entitled "Letters from Great Musicians" and the success of this book inspired her to write a second series of letters, in collaboration with Miss Alice Chapin. TheEtudeis indebted to Miss Rebecca Crawford, sister of the late Mrs. A. B.c. Cox, for permission to publish the following letter in this issue ofTheEtude. These letters are all imaginary notes to children, and are designed to present the biographies of the masters as though they were relating their life stories themselves.]

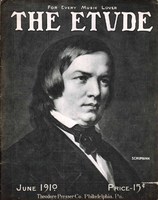

Born June 8, 1810. Died 1856.

"Ever striving to be first and to outrun the rest"

"It is the artist's lofty mission to shed light on the human soul."—Schumann.

Already four little ones were in my father's household when I came along. Perhaps because I was the youngest, perhaps from other causes, I was much petted during my childhood, and, of course, I enjoyed this and received it as my royal prerogative. Children are very apt to do this. I was very active and aggressive infant. I bubbled over with fun and frolic, and my ever active mind kept myself and all those about me well employed. When I was six years of age I was sent to school, where I proceeded to domineer over the other children. Playing at soldiers, was, of course, my favorite game. What boy does not like to play soldiers? But I was not content to be just a simple soldier; Oh, dear no, I must be the leader, 2nd as a rule the other boys gave me my own way. Not that I was stupidly selfish; I was generally leader in the game because I must be first, and the other boys loved me as cordially as I returned their affection.

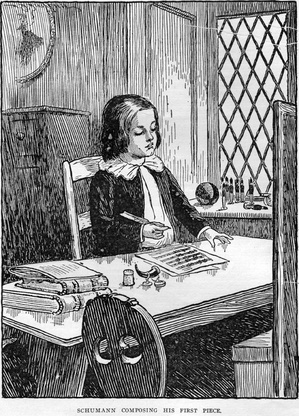

My lessons in music began after entering school. In a short time I was tumbling over my poor little fingers in my eagerness to get on, and though I knew nothing of thorough bass and harmony I was struggling to compose. I did write some little dances, very little ones. But what I really did well was to extemporize. I used to sketch in melody the different dispositions of those whom I knew, dwelling often on some prominent trait in their characters, and often I would hit them all so well that those who were listening would name the person intended by my playing with shouts of laughter.

MY AMATEUR ORCHESTRA.

I was not content with music alone, but made attempts at authorship also. I wrote robber plays, full of blood and fury, and then with the help of my playmates acted these wonderful dramas on a little stage, built especially for us. My dear father helped me in every way, now encouraging my dramatic efforts, now sympathetic and helpful over my music. He was a publisher, and in his bookshop, where I loved to sit, turning over the books, he introduced a beautiful collection of piano music. On every visit I discovered some new treasure, and one day, to my great delight, I found an overture of Rhigini's in orchestral score. I hurried

around among my friends and soon collected this formidable orchestra: Two violins, two flutes, a clarionet and two horns! We lacked in every essential save enthusiasm and courage. I directed our rehearsals, and undertook to fill in all the missing parts on the piano, not an easy task, but I would have attempted anything in those days. My father gave us all the necessary music stands and sat quietly in a corner during our performance, pretending to take no notice, but inwardly amused and perhaps a trifle interested— a select audience of one! Besides the overture, my little band studied other works, and I set to music the ninety-fifth Psalm, for a chorus and orchestra, enlarging our number for this work by a few boys who could sing. I usually wound up our rehearsal by extemporizing on the piano, giving musical portraits of my comrades. Can't you picture us now, a set of jolly, hearty boys, I sitting at the piano, the others clustering about, and my dear father lending dignity and manly weight to the boyish group?

One of the greatest treats of my boyhood was when, in Carlsbad with my father, I heard that wonderful pianist

Ignaz Moscheles. That concert I never forgot. It showed me what the piano could be made to say under truly musicianly fingers. Many years after, when I was a man, I had occasion to write, thanking Moscheles for the honor he had just done me in dedicating a Sonata to me. I told him that I, then a total stranger, had long preserved as a sacred relic a concert program his hand had touched more than thirty years before!

Moscheles' playing woke up all my dormant energies. I worked after hearing him with increasing enthusiasm, and also with a clearer vision of what work would accomplish. Gradually I edged my way out of the home nest, playing sometimes at evening entertainments of the Zwickau Academy, which I had entered in my tenth year, and also, playing often in a friend's house where the family were truly musical, and where I first saw some of the works of the great masters in art—Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. With what keen delight did I play the piano part in many of their quartets! I have already told you what an ambitious fellow I was, so will you be surprised when you hear that at one of our Academy entertainments I attempted Moscheles' Alexander variations, and Herz's variations, "If I Were a Youth?" This daring attempt at pieces considered to be so difficult so enraged my music master that he said that I might take care of myself; he would no longer instruct me.

My father now showed that he had been studying me to advantage. He understood me and was convinced that I was intended to be a musician. My mother opposed him with all her might. The life seemed to her too laborious and uncertain, and also she had some of the prejudice which is still floating about in the world against the artistic calling. Is it not strange that though instinctively we fill heaven with music and song, yet on earth we sometimes feel disposed to cold shoulder our musical brother? Perhaps it is because we are inwardly convinced that he may cold shoulder us hereafter.

THE CHOICE OF A CAREER.

My father, however, had been rendered so unhappy in his youth by the opposition he had encountered in his choice of a profession that he was determined to shield his children from all such bitterness, and accordingly he wrote to Carl Maria von Weber asking him to undertake my musical education. Though the master consented, this scheme was never carried out, and I therefore went on with my school life, devotedly studying music and attempting to compose. But foolish boy that I was! I did not realize that to be a composer I must master the theory of art, and for a long time I neglected counterpoint, thorough-bass and all the studies that make a musician. I wanted all the delights without the drudgery of the art. One who lives in an air castle will sooner or later find himself houseless, his beautiful castle being blown away. So it was with me, and soon my air castles came down with a crash—if air castles can crash. When I was sixteen my father died, and though his loss was a great and terrible grief to me, it was rendered still more bitter by the fact that in losing him I lost the sole supporter of my desire for an artistic career. In the year following his death my mother and guardian resolved that I must study a profession, which should be the serious business of life, while music would do as a plaything or genteel amusement. Accordingly I was packed off to Leipsic to begin a study of the most irksome kind—that of law. Don't make the mistake of finding fault with my mother, she did what she thought was for the best, and nothing would make me more angry than for anyone to blame her. I worship my mother, and she was always a fond and loving parent. Whenever I wrote to her my affection showed itself in numberless terms of endearment, and on her part, she was ever sending me some little token of remembrance or work of her hands to make me more comfortable.

UNIVERSITY DAYS AT LEIPSIC AND HEIDELBERG.

I enjoyed my student life in many ways. I practiced regularly and with much more assiduity than I studied law. I made new friends and met again some old ones, and I indulged in the jollifications German youths love. Fencing pleased me. I was like the others, neither better nor worse, but the longer I studied the more intense grew my hatred of law. I was often melancholy and had tremendous fits of the blues. By the way, I had almost forgotten to mention that when I was fourteen years of age my nature seemed to undergo a change. I grew more quiet, lost my constant flow of high spirits, and became moody and reserved. This reserve was destined to grow stronger as I grew older. Now, however, during my stay in Leipsic I worshipped at another shrine besides that of my music—that of "Jean Paul." I quoted continually from his writings; I wrote things myself which I called "Jean Pauliads;" I took a journey with a friend to Bayreuth and lingered for a glorious day among the scenes endeared to me by his genius. We also visited Munich and met there that great poet and unhappy man, Heinrich Heine. In afterlife I set many of Heine's poems to music, welding so closely song and harmony that neither is complete without the other.

Leipsic seemed to me a very stupid little town when we returned to it after this delightful journey, but as good fortune would have it, I soon made the acquaintance of Frederick Wieck, a charming man and a cultured musician. He had a little daughter, then eight years of age, who was a marvel of musical development. With my mother's consent, I began to study the piano with Wieck, so that the last year of my stay in Leipsic slipped pleasantly away. In 1829 I went to Heidelberg, and what a "life of flowers," as I called it, I led! With a few friends I took many short excursions among the beautiful suburbs, and we also made longer trips to Baden Baden.

EXCURSIONS AND SOCIAL GATHERINGS.

On all these journeyings I carried a dumb piano and practiced exercises while we talked. During one of my holidays I had a glorious journey through Italy. Is it necessary to say how much I enjoyed it? How beautiful I thought the women, and how musical seemed the language? I studied Italian so faithfully while in Italy that I was able to translate some of Petrarch's sonnets into German. Of course, I fell in love on this journey. I wonder if my love-making at that time was not indulged in just to keep myself in the fashion ? It was so very real at the time, but never lasting.

All these junketings were costly, and let me whisper it gently—I was continually in debt! I never could make both ends meet, and as to tying the knot, that was entirely out of the question. I was obliged to write very often, begging my guardian to forward money, and when he delayed in so doing I was reduced to a sad plight.

As you know, I was still supposed to be a law student, but poor law and jurisprudence were being shoved out of doors by music. I rose early in the morning in order to have more time to practice, and sometimes worked for seven hours in the morning, passing a glorious musical evening with my friends. I was soon well known in Heidelberg, and the circle of those who listened to my improvisations grew even wider. I was invited into musical society, but I never enjoyed being made a lion. When in the proper mood I improvised; when not in the mood I would not do so, and thus sometimes offended those who had before regarded me with liking. Once I played at quite a public concert, and should have felt terribly nervous only that I noticed that my friend who turned the leaves for me was so frightened as to be quite pale. This amused me so much that I quite forgot myself. After that appearance I was invited to play at several other concerts, but I declined all offers, even refusing to go into society, and withdrew more and more into myself. I was bothered in mind and felt best when alone.

THE "PARTING OF THE ROADS."

The vacation was drawing near when I must return home, and then all my misdeeds would be disclosed. My family would soon discover that I knew very little law. After deep thought and with much anxiety I wrote to my mother, telling her that my whole life had been "a twenty years' war between poetry and prose, or music and law." That I grew more and more attached to music, and that now I stood "at the parting of the roads." I must choose and abide by my decision. I knew she had ever withheld me from music because she had feared the difficulties in

my path; we had always called music ''an uncertain future and a precarious livelihood;" but again I urged my overwhelming passion for art, and I begged her to write to Herr Wieck at Leipsic and ask his opinion of my ability, for I would willingly abide by his decision. My mother did write to him and received a reply so favorable to myself that on the strength of it she decided in my favor, though my brothers and my guardians bitterly opposed her.

What did I care for them! I was wild with delight. I wrote an enthusiastic letter to my dear old master, putting myself under his tuition unreservedly, and, after extracting some much-needed money from my reluctant guardian (he kept me waiting till I threatened to borrow at exorbitant interest), I paid a short visit home and then flew to Leipsic to fulfill the dearest wish of my heart and consecrate myself to art. I felt capable of overturning mountains, but my way of overturning them was to run bang at them and try to knock them down; to tunnel under them is wiser. I calculated that five years' hard work would give me technical perfection as a piano virtuoso, for that was then my musical ambition; but I soon waxed impatient and was sure that I could strengthen my fingers more rapidly than Wieck's execises (sic) were doing. I recalled to mind a device a friend and myself had developed while in Heidelberg. Never mind what it was. By it I hoped to strengthen my troublesome fourth finger, and by it I stiffened forever that finger and destroyed all my hopes of ever being a pianist. When my right hand, on which I had tried this wonderful invention, grew entirely lame, I resigned myself to the inevitable and began to study the theory of music. If I could not play I would compose, and all my compositions written before this time show how profoundly ignorant I was of almost the rudiments of composition. If you don't believe this, just look over my first published work, which owed its conception to a lovely girl. I took her name—Abegg—for the foundation of my theme and worked some simple variations upon it.

A JOURNALISTIC ENTERPRISE.

While I was at last pegging away at what I should have studied long before, and while my master, Herr Dorn, was doing his best to keep me down to rule, Chopin's first published work appeared. I was enchanted with them, but the world received them with such indifference that I, burning with enthusiasm, wrote, I believe, the most fantastic, eulogistic criticism that ever was penned. This was my first appearance as a musical critic, but not my last, for two years afterwards, with other musical friends, I started aNew Journal of Music. We were all enthusiastic and determined to take up the cudgels for pure art. In Germany the honored dead were disregarded, the noble living artists among us were hardly recognized, while second- and third-rate people were worshipped. Our "New Journal" started with a grand aim, and in it I was able to review the work of many a young and struggling musician by bringing him into notice and giving him the praise he deserved. Our Journal was successful with the musical public, who liked its tone. In order to write more freely I conceived the idea of inventing several people of different temperaments; to these imaginary beings I gave names. Florestan, Eusebius and Rarr were the chief characters, and these people united in an alliance I called the "David's bündler." Florestan was the powerful and passionate, Eusebius the mild and dreamy side of character.

At last I fell in love, never to fall out again, and with whom? Why, with the daughter of my teacher, whom I had known as a child, and had frightened, too, with terrible ghost stories many a time! She had grown into charming girlhood and womanhood, and was not only a gifted woman, but a wonderful player. Clara Wieck had become my idol and she returned my love. Her father would not hear of me as a suitor for his darling child, and while I suffered under his positive refusal to allow us to marry, I composed and composed and composed. A concerto, sonatas, theDavidsbűndler, Kreisleriana and some other works will tell, to those who can read, the story of my mind at that time. Often was I disheartened. The coldness of publishers, the apathy of musical critics, was awful. The one would not take my works, and the others ignored them when they were published. What could I do under such depressing circumstances?

However, my belief in myself and my love for Clara sustained me, and in the end I triumphed. I was obliged to force Herr Wieck to give me his daughter, but have her I would, and in 1840 we were married. In that year also I wrote many, many songs. It was a year of song for me. My wife and myself led a blissful home life. I grew more and more a home body, but Clara's reputation as a pianist had to be considered, so we made several tours, my wifes' playing always arousing enthusiasm, and when she played my pieces I could not have asked for a more sympathetic interpreter. If I could have kept my health I would have had all that man could have, but I often suffered much. A morbid restlessness grew upon me; perhaps I already saw the cloud which was so soon to overshadow me and blot me from the ranks of thinking, feeling men. First I gave up my journal, then we went to live in Dresden, hoping the change would benefit me; but no benefit was lasting. When bright gleams came to me I wrote still. Already Paradise and the Peri had been composed. I also wrote one opera,Genevieve, and composed the music to Manfred. That was a subject that suited me well, and I never devoted myself to my own composition with such lavish love and power as toManfred. I enjoyed, too, myFaust music.

But I have written enough. I couldn't have told you one-quarter as much about myself, for I seemed to lack the power of expressing my feelings in speech. When I met my own children I used to look at them and say: "Oh, there you are, you dear little things," and pass on. When Wagner and I met I complained that he talked all the time, while he said that I had not a word to say for myself. Don't you believe that of me; I can still say many things to you through my music, and you will believe, I am sure, that a musician has somewhere about him, hidden away possibly, warm, loving feelings. With the kindest feeling in the world, I say to you, my dear little friends, good-night and good-bye.

ROBERT SCHUMANN.