TOLD BY HIMSELF EXPRESSLY FOR “ETUDE” READERS

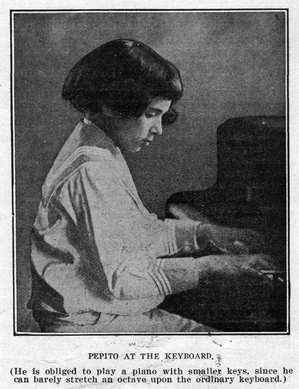

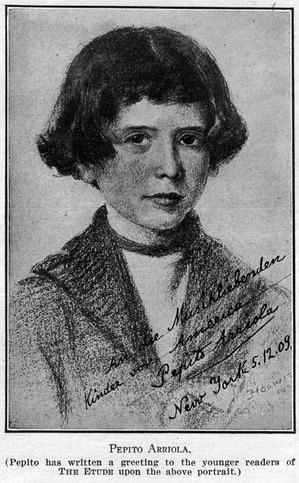

[Editor’s Note.—Some years ago The Etude printed three portraits and an account of the remarkable child pianist, Pepito Arriola, who was then astonishing the musical critics of Europe by his wonderful precocity. However one may feel about the advisability of exploiting a prodigy, it is nevertheless a fact that a very great number of the famous masters of the world have been musically precocious. It would appear from this that musical talent when of a pronounced character makes itself evident at a very early age.

A representative of The Etude investigated the case of Pepito Arriola with a view to presenting to our readers some interesting educational facts regarding the most astonishing case of precocity known in recent years, with the possible exception of Master Sidis, the child mathematician of Boston.

Pepito was born in Madrid on the 14th of December, 1897. A careful investigation of his ancestry reveals that no less than twelve of his forefathers and relations have been pronouncedly musical. His father was a physician and his mother a musician. The child’s early musical training was given to him by his mother, and, as he tells in his own story, was along singularly natural lines.

He is apparently a perfectly healthy, natural, modest child, with all the inclinations of the average boy of his years. He shows far greater delight, for instance, over the costly and beautiful jeweled pins and cuff-buttons given him by Kaiser Wilhelm, than he does over the enthusiastic enconiums (sic) of Richard Strauss, Arthur Nikisch, and other of the greatest European musicians of the day. His general education has apparently been liberally conducted and his favorite avocation is astronomy. In strange contrast to this, he plays with his toys as any boy would.

He is well versed in the literature one many years older might choose to read. He has strong nerves, perfect poise and no fear of public performance. His ideas upon musical interpretation are those of a real virtuoso and his catholicity and breadth can only be described as astonishing.

The Etude representative is a teacher of many years’ experience. In examining Pepito’s playing he found him practically flawless in the matter of making mistakes of any kind. He never seems to miss a note in the most complicated and difficult compositions found on the modern concert program. His playing indicates individuality and a deep appreciation of artistic beauty. Pepito speaks German, Spanish and French, but little English.]

The following was secured expressly for THE Etude, and an effort has been made to preserve in English the same style of vocabulary and idioms used in German by Arriola.

MY EARLIEST RECOLLECTIONS.

“So much that was of interest to me was continually occuring (sic) while I was a child that it all seems like a kind of haze to me. I cannot remember when I first commenced to play, for my mother tells me that I wanted to reach out for the keyboard before I was out of her arms. I have also learned that when I was about two and one-half years of age, I could quite readily play after my mother, anything that the size of my hand would permit me to play.

I loved music so dearly, and it was such fun to run over the keyboard and make the pretty sounds, that the piano was really my first and best toy. I loved to hear my mother play, and continually begged her to play for me so that I could play the same pieces after her. I knew nothing of musical notation and played entirely by ear, which seemed to me the most natural way to play. At that time, word was sent to the King of Spain, that I showed talent, and he became interested in me, and I played before him.

I loved music so dearly, and it was such fun to run over the keyboard and make the pretty sounds, that the piano was really my first and best toy. I loved to hear my mother play, and continually begged her to play for me so that I could play the same pieces after her. I knew nothing of musical notation and played entirely by ear, which seemed to me the most natural way to play. At that time, word was sent to the King of Spain, that I showed talent, and he became interested in me, and I played before him.MY FRIENDSHIP WITH ARTHUR NIKISCH.

A short time afterward, Herr Arthur Nikisch, conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra at Leipsic, and at one time conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in America, came to Madrid to conduct the Philharmonic Orchestra for a special concert. Some one told him about my playing and I was permitted to play for him. He became so interested that he insisted upon my being taken to Leipsic for further study. I was then four years of age, and although musical advantages in Spain are continually increasing, my mother thought it best at the time that she should follow the great musician’s advice and that I should be taken to the German city.

I want to say that in my earliest work, my mother made no effort to push me or urge me to go ahead. I loved to play for the sake of playing, and needed no coaxing to spend time at the keyboard. In my very early years I was permitted to play in public very little, although there were constant demands made to engage me. I was looked upon as a kind of curiosity and my mother wanted me to study in the regular way with good masters, and also to acquire more strength before I played in public very much.

I did, however, play at the great Albert Hall, in London. The big building holds 8,000 people, but that was so long ago that I have almost forgotten all about it, except that they all seemed pleased to see a little boy of four playing in so very big a place. I also played for royal personages, including the Kaiser of Germany, who was very good to me and gave me a beautiful pin. I like the Kaiser very much. He seems like a fine man.

MY FIRST REGULAR INSTRUCTION.

My first teacher, aside from my mother, was a Herr Dreckendorf, of Leipsic. He was very kind to me and took the greatest pains, but the idea of learning the notes was very distasteful to me. I was terribly bored with the technical exercises he gave me, but have since learned that one can save much time by practicing scales and exercises. Although I do not like them, I practice them every day now, for a little while, so as to get my fingers in good working order.

In about six weeks I knew all that was expected of me in the way of scales in octaves, sixths, thirds, double thirds, etc., etc., and my teacher commenced to turn his attention to studies and pieces. For the first time I found musical notation interesting, for then I realized that it was not necessary for me to wait until some one else played a piece before I could begin to explore its beauties. Ah! it was wonderful, those first days with the pieces. I was in a new country and could hardly wait to master one at a time, so eager was I to reach the next one and see just what it was like.

Herr Dreckendorf gave me some studies by Dussek, Cramer, the Inventions of Bach, etc., but before long the fascination of playing beautiful pieces was so great that he found it hard to keep me away from them.

EARLY REPERTORY.

So hungry was I to find new musical works that when I was eight and a half years old I could play from memory such pieces as the B flat minor Scherzo, the A flat Major Polonaise, and most of the Valses and Etudes of Chopin. I also played the Sixth Rhapsody of Liszt and the C minor concerto of Beethoven.

In the meantime we moved to Berlin and this has been our home ever since, so you see I have seen far more of Germany than of my native country, Spain. In fact it seems more natural for me to speak German than Spanish. At the age of seven it was my good fortune to come under the instruction of Alberto Jonas, the Spanish virtuoso, who for many years was at the head of a large music school in America. I can never be grateful enough to him for he has taught me without remuneration and not even a father could be kinder to me. When I left Berlin for my present tour, tears came to our eyes, because I knew I was leaving my best friend. Most of my present repertory has been acquired under Jonas and he has been so, so exacting.

He also saw to it that my training was broad, and not confined to those composers whose works appealed most to me. The result is that I now appreciate the works of all the composers for the piano. Beethoven I found very absorbing. I learned the “Appassionata” Sonata in one week’s time, and longed for more. My teacher, however, insisted upon my going slowly, and mastering all the little details.

I have also developed a great fondness for Bach, because I like to find how he winds his melodies in and out, and makes such beautiful things of them. I play a great deal of Bach, including the G minor organ Fugue, which Liszt played the devil with in arranging it for the piano. Goodness knows, it was difficult enough for the organ in its original form! I don’t see why Liszt wanted to make it more difficult.

Liszt is, of course, considered a great master for the piano, and I play his works with great delight, especially the “Campanella” with its beautiful bell effect, but I cannot look upon Liszt as a pianistic composer in the same way that one thinks of Chopin as a pianistic composer. The piano was Chopin’s natural tongue. Liszt’s tongue, like that of Beethoven, was the orchestra. He knew no difficulties, according to the manner in which he wrote his own works. Consequently one must think of the orchestra in playing Liszt’s works, while the works of Chopin suggest only the piano.

During most of my life my practice has never exceeded two hours a day. In this country, while on tour, I never practice more than one and one-half hours. This is not necessary because of the concerts themselves, which keep up my technical work. I never worry about my fingers. If I can think the pieces right, my fingers will always play the notes. My mother insists upon my being out in the open air all the time I am not studying and practicing, and I am out the better part of the day.

At my practice periods, I devote at least fifteen or twenty minutes to technical exercises, and strive to play all the scales, in the different forms, in all the keys, once each day. I then play some of my concert numbers, continually trying to note if there is any place that requires attention. If there is, I at once spend a little time trying to improve the passage.

It is very largely a matter of thinking the musical thought right, and then saying it in the right way. If you think it right, and your aim at the keyboard is good, you are not likely to hit the wrong notes, even in skips such as one finds in the Rubinstein Valse in E flat. I do not ever remember of hitting the upper note wrong. It all seems so easy to me that I am sure that if other children in America would look upon other examples in the same way, they could not find their work so very difficult. I love to practice Chopin. One cannot be so intimate with Bach; he is a little cold and unfriendly until one knows him very well.

GENERAL EDUCATION.

I have said that we play as we think. The mind must be continually improved or the fingers will grow dull. In order to see the beauties in music we must see the beauties in other studies. I have a private teacher who comes to me in Berlin and teaches me different studies. I have studied some Latin, French, and the regular school studies. Electricity interests me more than I can tell you and I like to learn about it, but my greatest interest is in the study of astronomy. Surely nothing could be finer than to look at the stars. I have friends among the astronomers of Berlin who let me look through their telescopes and tell me all about the different constellations and the worlds that look like moons when you see them enlarged. It is all so wonderful that it makes one never cease thinking.

I also like to go to factories and learn how different things are made. I think that there are so many things that one can learn outside of a schoolroom. For instance, I went to a wire factory recently, and I am sure that I found out a great many things I might never have found out in books. One also learns by traveling, and when I am on my tours I feel that I learn more of the different people and the way they live than I ever could from geographies. Don’t you think I am a lucky boy? One must study geography, however, to learn about maps and the way in which countries are formed. I have toured in Germany, Russia, and England, and now in America. America interests me wonderfully. Everything seems so much alive and I like the climate very much.

THEORETICAL STUDIES.

Musical theory bores me now, almost as much as my first technical studies did. Richard Strauss, the great German composer, has very kindly offered to teach me. I like him very much and he is so kind, but his thundering musical effects sometimes seems very noisy to me. I know many of the rules of harmony but they are very uncomfortable and disagreeable to me.

I would far rather write my music as it comes to me. Herr Nikisch says that when I do it that way, I make very few blunders, but I know I can never be a composer until I have mastered all the branches of musical theory. I am now writing a symphony. I played some parts for Herr Nikisch and he has agreed to produce it. Of course the orchestral parts will have to be written for me, but I know what instruments I want to express certain ideas.

Putting down the notes upon paper is so tiresome. Why can’t one think the musical thoughts and have them preserved without the tedious work of writing them out! Sometimes before I can get them on paper they are gone—no one knows where, and the worst of all is that they never come back. It is far greater fun to play the piano, or play football or go rowing.

READING AND STUDY.

I love to read, and my favorite of all books is The Three Musketeers. I have also read something of Shakespeare, Goethe, Schiller, and many other writers. I like parts of the great Spanish novel Don Quixote, but I find it hard to read as a whole. I think that music students ought to read a great deal. It makes them think, and it gives them poetical thoughts.

Music is, after all, only another kind of poetry, and if we get poetical ideas from books we become more poetical, and our music becomes more beautiful. The student who thinks only of hammering down keys at the piano cannot play in a manner in which people will take pleasure. Piano playing is so much more than merely pressing down keys. One has to tell people things that cannot be told in words—that is what music is.

AT THE CONCERT.

I do not know what it is to be nervous at concerts. I have played so much and I am always so sure of what I am going to play that nervousness is out of the question. Of course I am anxious about the way in which audiences will receive my playing. I want to please them so much and don’t want them to applaud me’ because I am a boy, but would rather have them come as real music-lovers to enjoy the music itself. If I cannot bring pleasure to them in that way I do not deserve to be before the public.

My concerts are usually about one hour in length, although I sometimes play encores for some time after the concert. I make it a practice not to eat for a few hours before the concert, as doctors have told my mother that my mind will be in better shape. I want to thank the many friends I have made among the students who have come to my concerts, and I hope that I may have told them some things which will help them in their work.”