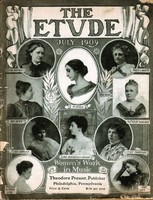

From an Interview Secured Exclusively for The Etude with

Mrs. Corinne Rider-Kelsey

[Editor’s Note.—Mrs. Rider-Kelsey is said to have been the first singer of American birth and American training to have met with a favorable reception in a European opera house. Mrs. Rider-Kelsey’s teachers were all American born. In 1908 she appeared at Covent Garden, in London, with pronounced success. She is best known, however, in America as an oratorio and concert soloist, and as having received the highest salary ever paid to a church singer in New York City.]

The success of the American girl as an opera singer is seldom attributed to that quality known as “temperament.” Temperament, as it is understood in Europe, is quite different from what is understood by it in America. There it means a knowledge of life and art which has been imbibed at the great centers of musical and artistic inspiration. Here we associate temperament with vivacity and personal magnetism. Our American girls have little opportunity to acquire temperament in the European sense. It is true that in our great cities we have fine music and great art museums, but these are beyond the reach of many of our American girls who at the same time seem to be gifted with phenomenally excellent natural voices. Just why they should possess such voices I certainly shall not attempt to state. The fact is they have this wonderful gift, and that perhaps is the chief reason that in a very large number of the leading opera houses in Europe during the past ten years the most applauded prime donne have been of American birth.

The success of the American girl as an opera singer is seldom attributed to that quality known as “temperament.” Temperament, as it is understood in Europe, is quite different from what is understood by it in America. There it means a knowledge of life and art which has been imbibed at the great centers of musical and artistic inspiration. Here we associate temperament with vivacity and personal magnetism. Our American girls have little opportunity to acquire temperament in the European sense. It is true that in our great cities we have fine music and great art museums, but these are beyond the reach of many of our American girls who at the same time seem to be gifted with phenomenally excellent natural voices. Just why they should possess such voices I certainly shall not attempt to state. The fact is they have this wonderful gift, and that perhaps is the chief reason that in a very large number of the leading opera houses in Europe during the past ten years the most applauded prime donne have been of American birth.

The American girl may secure her musical and vocal training in America, and then if she has the good fortune to travel she seems to accumulate temperament at a most astonishing rate. This, together with her fine voice and a rational American training, equips her to compete with the great singers of the other countries of the world.

HER NATURAL APTITUDE.

The American girl has remarkable natural aptitude. Like her big brother she can adapt herself to new conditions of life in a manner quite surprising to Europeans. She is normally reserved, quiet and sensible. Judged by her home and social surroundings it would seem that she should be far better adapted to the concert and oratorio stage than to opera. In opera her mode of living must be entirely changed. She soon, however, becomes perfectly at ease before the footlights, notwithstanding her Puritan ancestry or a narrow education. Those who have experienced both lines of musical occupation have no hesitation in saying that the concert and oratorio field demands a finer musical training than that expected of operatic singers. There are delicate differentiations of tonal and rhythmic interpretation that are lost in the great opera house, but which are imperative in the recital. Nevertheless, the glamour of the stage which accompanies opera often induces some of our young American singers who might be very successful in oratorio to forsake everything else for opera.

SPECIAL DRAMATIC STUDY.

The young aspirant for operatic honors should secure a special course in dramatic study if possible. There are some excellent schools in America and the graduates of these schools have a knowledge of acting and stagecraft that frequently secures them positions in representative American companies. It is a mistake to suppose that a working knowledge of acting can be acquired by intuition in a comparatively short experience before the footlights. The matters of exits, crosses, etc., and other little technicalities, are stage conventions which embrace but an insignificant fraction of the art of acting. They in themselves must be mastered in a manner which will remove all suggestion of artificiality, but the real art of acting embodies laws of interpretation which are as comprehensive as the universe and as broad as mankind. The student in the dramatic school acquires a knowledge of a few of these laws. The remainder demand the study of a lifetime. The modern operas require the performers to be actors as well as singers. The time is past when the operatic stage was nothing more than a frame for a few exhibitions of vocal pyrotechnics. Such operas as “Carmen,” “Louise” and “Madama Butterfly,” to say nothing of the great Wagnerian music dramas, require singers with histrionic ability and training. In fact, it often happens nowadays that many of our most celebrated opera singers have won their reputations from their acting rather than their singing.

Our American girls have also decided dramatic ability. They are perhaps the most traveled young women in the world. Moreover, the wonderful library system, as well as the popularity of the cheap magazines, gives them an insight into life at first hand, and at second hand through the eyes and pens of authors, that few young women of the Old World ever acquire. Some of them hope to get the dramatic experience to fit them for opera by actual work upon the stage. They join the chorus of some touring company and in some rare cases they have succeeded. In most cases they always stay in the chorus, hoping and dreaming of the glorious future that never comes. Those who want to “begin at the bottom” in this way must have a wonderful amount of stamina. They usually have to wade through a deep and long dramatic mire that could have been avoided by securing an adequate training in some good dramatic school. The managers are unfortunately loath to give big parts to the singer they have always thought of as a chorus girl. In Europe the conditions are slightly different. There, as I have said, our girls have won out by their fine voices and excellent tone production. But they have had to work for success, and any girl with a good voice who thinks that she can go abroad and drop into a fine position, in a European opera house without having had previous experience is greatly mistaken.

Moreover, the managers are loath to give big parts to singers who have not acquired a big European reputation. It is practically impossible to jump from the chorus to an important part, no matter how pronounced one’s ability or how excellent the voice. It has been very gratifying, however, to see so many able American singers in the casts of our great American opera companies. With very few exceptions, however, these singers have been obliged to acquire great European reputations before they have been able to secure positions in an American company.

THE TIME TO COMMENCE VOICE STUDY.

Prominent singers are often asked what time voice study should be commenced. It has always seemed to me that eighteen or nineteen was young enough for a girl to start studying. I am aware that many have started at a much earlier age and have been successful. If a girl is very strong, she may start at the age of sixteen, but there is always a risk if an earlier start is made. If a younger pupil were to practice only under the surveillance of an able teacher, the risk would be lessened. It might also be an excellent plan to have the child who shows indications of having an unusually fine voice visit a competent voice teacher occasionally for inspection and examination purposes, since children frequently fall into very bad habits from their natural tendency toward mimicry. The child has the misfortune to hear execrable singing upon some occasion. He hears the audience applaud the singer and assumes that such singing is desirable. The she imitates the singer, and thus acquires habits that it may take months to eradicate in after-life.

THE FIRST STEPS.

Our American girls are all inclined to study at too rapid a rate. Slow study is absolutely essential at the start. Many singing teachers sacrifice a pupil’s future just to make a showing with a few brilliant songs. Some do not hold themselves responsible for this, as they contend that the parents of the pupils demand such a showing. The first exercises should be of the simplest possible character, as much depends upon the pupil’s ability to comprehend an exercise. If the pupil does not have the right intellectual grasp of the exercise, success is not likely to be forthcoming. I have known teachers to spend three years in giving exercises. Unquestionably the greatest waste in vocal training today comes from the fact that many teachers are men and women who have failed as singers, and who feel that it is an easy matter to become a teacher. The real teacher requires years of study and preparation. He must be methodical, but must have such a variety of means at hand so that he can find at once the best remedy for all sorts and conditions of vocal troubles. He must be able to substantiate his promises with real results—that is, by producing pupils who can sing. Avoid the teacher of great pretensions who is unable to point to a successful pupil.

It frequently happens that a magnetic personality has attracted many pupils to teachers who have little real ability. They talk in such a manner that people are convinced of their ability, but in voice training, as in everything else, it is not talk that counts. Talking and advertising make a certain kind of publicity, but if this publicity can not be supported with real achievement the teacher rarely has enduring success. The unfortunate part is that as soon as one charlatan has been exposed there is usually another to take his place, and thus the musical public is continually exposed to deception and fraud. There are, however, many excellent teachers, and it is not difficult to locate them by their pupils.

THE AMERICAN GIRL’S SUCCESS DUE TO AMERICAN TEACHERS.

The success of the American girl has in part undoubtedly been due to her American teachers. The American seems to be a born teacher. He has the faculty for making things clear to his pupils, and the practical element in his character leads him to strike directly for essentials and not to waste time over non-essentials. Of course, there are a great many excellent teachers abroad, but it not infrequently happens that the European teacher gets the credit for training that has been nine-tenths American. Girls go abroad to study things that could be learned at home, at far less expense and amid surroundings vastly more congenial and beneficial. The girl who studies abroad and who has not abundant funds is placed in a very undesirable position. Unless her mind is free from care she is not in proper condition to pursue her studies. If she is continually wondering where the next money is coming from and when it will come, she will find it almost impossible to keep her mind upon her work. Music study requires a free mind and great persistence, coupled with regularity and comfortable surroundings. If she can secure these at home, she need not imagine that conditions will be any different three thousand miles away from home, in a strange country, among strange people, speaking a strange tongue.

GENERAL EDUCATION VALUABLE.

Perhaps another reason why our American girls have been so successful in opera is that they have had the advantages of a somewhat better general, higher education than is open to most young women in Europe. Higher education in many instances is reserved for the boys in most European countries. While in later years the girls have been offered equal advantages, custom and tradition frequently stand in the way of their accepting these advantages. No matter how much time the musical and vocal training of the aspiring vocalist may consume, there still should be reserved sufficient time to secure a good school education, not necessarily a college training, but, if possible, a high school training. She must have something to make her brains act. If she can secure a college training, so much the better. It will make everything she does in afterlife take on a broader and higher character. In fact, if more attention were to be devoted to general educational work and less to requiring young singers to undertake rôles far in advance of their strength and ability, the results would be far better. The voice in youth demands lightness and elasticity. Most of the great singers of to-day have been trained to sing coloratura roles in their youth. Age brings the dramatic soprano. The voice grows deeper and the tones become stronger and fuller. I heard a young woman in London, a year ago, who I am quite certain will lose her voice in time. She was nineteen, and possessed a really beautiful voice, but she was undertaking the heaviest and most dramatic roles. She will surely regret this in years to come.

SIMPLICITY IN TEACHING THE GREAT NEED.

The tendency of the times is toward simplicity in voice teaching. The day of the complicated and useless exercises is past. Take the matter of breathing, for instance. If pupils would breathe in the most natural manner they will in most cases adopt the right methods intuitively. I have never been of an investigating disposition, but it has always seemed to me more or less of a waste of time to instruct the pupil in the various little details of physiology of which some teachers make such an important point. More can be gained by watching an infant breathe than by studying libraries of books of physiology. Breathing always seemed to come natural to me. I never affected the high breathing that is generally considered ruinous. Of course, I have worked on little points in breathing, but the main points are entirely natural.

VALUABLE VOCAL EXERCISES.

The young singer will require exercises adapted to his immediate needs. It is quite impossible to indicate any set of exercises and give printed directions for their use. In voice teaching the presence of the teacher is imperative. For this reason it is quite out of the question to teach voice by the correspondence methods commonly advertised. Personally, I practice scales every day, but that in itself means nothing to the reader, for it is how the scales are practiced that counts. For instance, one of my teachers taught me to blow upon the edge of a card held against the pursed lips and sing the scale slowly to the word “who.” The vibration of the card accompanying the singing when the exercise is properly done is an indication of the forward placement so greatly to be desired. I find the exercise of immense value in focusing my voice forward, but it is one that cannot be safely intrusted to the student without careful instruction. I related it to a teacher in London upon one occasion, and later I visited her and found her pupils practicing the exercise in a manner that could only lead to bad results. Where they should have had the muscles relaxed, they were tense, and the whole lesson illustrated the tendency of teachers to grasp anything to introduce novelty, no matter whether they have given it sufficient investigation or not.

The exercise with the card assists me to secure “balance” in tone. That is, it is a test of the breath conditions and informs me whether I am using too little or too much breath. Its indiscriminate use in the hands of a novice is hardly to be recommended.

Girls from different parts of our country often require different methods of instruction. The girl from the Middle West, for instance, says her “ah” with a peculiar burr that is very difficult to describe but which is an undesirable provincialism. This, of course, will affect her whole tone production until it is properly remedied. It was one of the things that I had to overcome, and I found the following exercise of value:

This, of course, was practiced upon the different degrees of the scale within the most comfortable range of the voice. Under the care of an able teacher this will correct the fault of which I have spoken.

A somewhat different treatment is required by the girl from the East. She seems to need, most of all, practice upon the Italian vowel “ah.” This, together with exercises in the Italian languages, is the best corrective for her tendency toward a nasal tone. These points, however, must be developed by the teacher, as very few pupils have the correct idea, and it is often impossible to hear oneself as another can hear.

NATURALNESS IN SINGING.

Most all great singers feel the necessity for naturalness in singing. Marvelous as the phenomena of voice are, the process of singing is, after all, a purely natural one. So many rules are imposed upon the average student that he becomes self-conscious. Audiences in these days are very quick to detect self-consciousness and artificiality. Anything that savors of the unnatural is undesirable. The tremolo is unnatural, for instance, and although it was desired by the temperamental Italians of bygone days, it is all out of place upon the American concert stage. What our audiences want most is a sweet, clear, resonant, sympathetic tone combined with evidence of musicianly ability and rational and artistic interpretative ideas. Many teachers seem to be working away from these ideals instead of toward them. Of course, there are hundreds of little points which must be studied definitely. It took me years, under the guidance of the most painstaking of teachers, to learn how to phrase properly and effectively, but the teacher was careful at all times not to impose anything suggesting artificiality. It was rather a study to discover the most natural or normal means of taking my breath so that the phrases might not be delivered in an inartistic manner.

Notwithstanding the extraordinary past of the American girl in the history of song, her future is still more propitious and she stands ready to compete with the great singers of all other nations upon an equal footing, particularly in the field of opera.