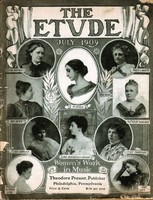

[The following have been taken, at the suggestion of Mme. Blauvelt, from various authentic articles and letters of Jenny Lind, “the Swedish Nightingale,” whose wonderful voice and art created one of the most extraordinary furores ever known in the history of song. Jenny Lind was born October 6, 1820, at Stockholm, and died at Malvern, England, in 1887. She sang in America in 1850-52. In Boston, she married Otto Goldschmidt, a composer and conductor of ability, who was her accompanist at her concerts. From 1883-86 she was professor of singing at the Royal College of Singing in London. The picture of Jenny Lind, printed with this department, was loaned by Mme. Blauvelt, who possesses a most remarkable collection of autographed photographs of famous people, most of whom she has known personally.— Editor of The Etude.]

IMITATION IN SINGING.

It may be inferred from the following that Jenny Lind was opposed to imitation in singing. The following is part of a letter written to Mme. Lindblad in 1841, when the singer was still studying in Paris:

“You must know that I am beginning to be an ape—a fact of which I was not aware until yesterday. I was singing to Mlle. du Puget and she seemed a little bit surprised when just once or twice I displayed all my powers—you know what I mean—and she looked at me as though she had not given me credit for this. First she said that I sang in Persiani’s style, and then in Grisi’s, and she was kind enough to say that it was excellently imitated—could not, in fact, be better. The compliment was rather hard to digest. I was so ashamed that for a long while I could not look up. But, after a considerable pause, I asked, ‘Do you really think so?’ with a feeling of pride which my look, even the look of my back, must surely have reflected. God help me! I am so proud that I cannot bear people to say I ‘imitate.’ I loathe the very word to such an extent that I cannot conceive what its inventor was thinking of. It seems to me that to take what is another’s and use it for one’s self, and then to make believe that it is one’s own, is positively to steal. But I see so quickly the impression of what is good or bad that I should not feel surprised if I have caught something from the Italian opera, which I have already visited pretty frequently, but, be this as it may, the reminiscences I am carrying away from the Italian opera here are much better than those connected with Stockholm and the school and style that prevail there.”

MENDELSSOHN TO JENNY LIND.

The bond of friendship between Jenny Lind and Felix Mendelssohn was very cordial and he wrote her many lengthy letters upon business and artistic matters. The following is interesting, as it reveals that he probably had her in mind for an opera for which it was his misfortune never to secure a satisfying libretto:

“You will certainly meet with such a reception in England that you will be able to think of it with pleasure throughout the whole of your future life. When the English once entertain a personal liking for anyone, I believe that no people are more friendly, more cordial or more constant; and such a feeling you will find there… . Mr. Lundy, also in the kindest manner, proposed that I should compose an opera for him, and I could only answer that on the self-same day on which I succeeded in getting a good libretto on a good subject I would begin to write the music and that in doing so I should be fulfilling my greatest wish. He hopes to be able to secure such a libretto and has taken steps with regard to it.”

HER GREAT GENEROSITY.

Jenny Lind’s great charity and generosity is one of the most noble traits in her remarkable career. In her native land she insisted upon devoting practically all of the receipts of her concerts to the support of the unfortunate. She insisted that she had been a “child of the State” and that it was her duty to further the cause of the education of unfortunate children in the country of her birth.

In a letter written in 1848 to a distinguished citizen of Sweden she says:

“My most ardent wish is to be allowed to be of some lasting use to native art. To offer some kind of souvenir, more permanent than the quickly passing moments of my appearances on the boards; and to prepare for my countrymen enjoyments of the loftier kind for the years to come, when my own efforts shall have ceased. I hope to do this by laying the foundation of a college where young minds may be consecrated to both art and virtue.

“Having been myself, in childhood, a witness of the privations and trials through which the young and needy have to struggle in this profession, which holds so many thorns amongst the roses, I should count it the most beautiful gain of the singer’s gift if, by means of this, I could contribute to help those who are favored by nature, but ill-treated by fortune to a development of their talent in comparative be devoted to an institution for educating poor children who, while especially endowed for the stage, lack the care of parents or relatives, without which, in a moral and artistic respect, they either lose or else fail to reach the higher development for which their gifts would give reasonable hopes.

JENNY LIND’S PHENOMENAL VOICE.

Although most readers of the present day will think of Jenny Lind’s voice as that of the coloratura soprano, it is a fact revealed by history that her voice was not naturally flexible and that the flexibility was only produced after the greatest effort. Her normal range was from the B below the treble staff to the second G above the treble staff—two octaves and five notes. While her fioratura singing is described as being so beautiful that words are wanting to tell how remarkable it really was, it was the wonderful sweetness of the voice itself that made her greatest fame. One writer states that she had “all the volume and sonority of the true soprano dramatico, with the lightness and flexibility peculiar to the more ductile and airy soprano sfogato.”

Meyerbeer described her singing, in a letter to her, thus:

“What remains for your friends to wish for you Whom Heaven has so richly endowed? It has given you that great and sympathetic voice which charms and moves all hearts; the fire of genius which pervades your singing and your acting; and, in fine, those indelible graces which modesty and candor and innocence give only to their favored ones and which bring every enemy into subjection.”

Hans Christian Andersen, the Scandinavian author and writer of fairy tales, tells the following story of a poor poet whom he found on the streets of Berlin and took into his home. After Andersen had provided for the material needs of the unfortunate man he sought to encourage him by giving him a ticket for Jenny Lind’s concert.

“I asked him, therefore, whether I might venture to invite him to hear Jenny Lind. ‘I have already heard her,’ he said, smiling. I could not afford to buy a ticket, so I went to the man who provides the supers and asked him if I could not go as a supernumerary performer in “Norma.” To this he agreed. So I was dressed tip as a Roman soldier, with a long sword at my side, and in that guise appeared upon the stage; and I heard her better than anyone else, for I stood close beside her. Ah! how she sang and how she acted! I could not stand it, it made me weep; but they were furious at that. The manager forbade it and would never permit me to set foot upon the stage again—for one must not weep upon the stage.’”

While this is an excellent indication of Jenny Lind’s power over her auditors, the spectacle of a Roman soldier in tears must have been very amusing, and we can hardly blame the management of the opera house.

IDEAS ON VOICE TRAINING.

The efficacy of Jenny Lind’s “method” was shown by the great endurance of her voice. Aside from her concerts and recitals, she sang during her lifetime 677 times in opera. She sang in “La Sonnambula” alone ninety- eight times. Her whole training showed her the necessity for naturalness in voice study. Her breathing was so quick and effortless, it is said, that the closest observer was unable to detect her taking a breath. It is also stated that her diminuendo was so perfect that “it died away to an imperceptible point, so completely covering the end of the note that no ear could detect the moment at which it faded into silence.”

She was very particular about the trill, and in order that it might not result in the wobble, really nothing more than a bad tremolo, she used the following exercise, which is taken from a manuscript by the great singer:

Later the whole notes were left out and the exercise appeared thus:

Modern teachers would doubtless gradually increase the tempo of the exercise with the use of the metronome.

Modern teachers would doubtless gradually increase the tempo of the exercise with the use of the metronome.

Starting with the interval of the fifth and with the accent upon the upper note of the trill, and then gradually diminishing the interval, the trill may be developed in such a manner that all suggestion of the tremolo is avoided. The difficulty in intonation in the trill is in striking the upper note on the right pitch. When the trill is sung the accent generally falls upon the lower or principal note, but when the above exercise has been faithfully practiced it is an easy manner to sing the trill with the accent in the proper place.