Department for Singers

Edited for July with the assistance Of MME. LILLIAN BLAUVELT

Tone, the Groundwork of All Good Singing.

BY MME. LILLIAN BLAUVELT.

[Editor’s Note.—A biography of Mme. Lillian Blauvelt, together with a portrait, will be found in the “Gallery of Celebrated Musicians” for this month. We are sure that all of our readers will appreciate the assistance of so eminent an artist, in this special issue devoted to “Woman’s Work in Music.” Mme. Blauvelt’s great success in Europe has given American audiences but limited opportunities to hear her in recent years. She has toured in most of the great European countries, and has met with ovations everywhere. In Rome, the Order of St. Cecilia was conferred upon her. Only eight persons have been thus distinguished, and Mme. Blauvelt is the only woman and the only English-speaking artist to receive the honor. Next year Mme. Blauvelt is engaged for the Grand Opera at St. Petersburg and Moscow.]

The first consideration of every singer should be the quality of the tone. Execution, technique and interpretation are all vital matters, but without tone only the greatest of interpreters and singing actors can succeed. We frequently have our attention called to singers who have voices that, in themselves, are not particularly great.

Sometimes by dint of much work and natural histrionic ability they can acquire methods of conveying their thoughts to their audiences in such a way that their vocal deficiencies are forgiven. Sometimes, through the force of their mentality or through what has always seemed to me as nothing more than hypnotism, these singers sway great audiences in a most remarkable manner.

The singer with a beautiful tone but without temperament, mentality and artistic finish is always an aggravation. You hear the dulcet notes coming from a soulless body, and while they are pleasing, like the tones of a beautiful flute, you at all times have the distinct feeling that the singer is not bringing forth the best in the human voice.

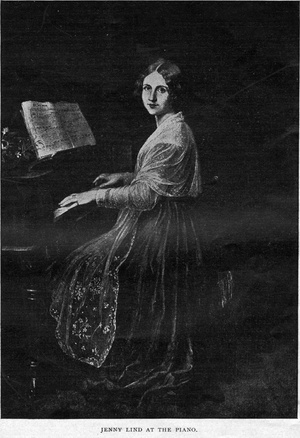

The artist who can combine technique, flexibility and mentality with her singing must of necessity be the greatest artist. Such an artist was Jenny Lind, to whom I shall have occasion to refer later. She has been my ideal during my entire musical life, and I continually study her writings. Apart from her wonderful natural ability as a singer, she had the art of expressing herself with an individuality which amounted to genius. I shall quote from her to some extent.

One of the most desirable attributes of a good tone is individuality. If the tone is not individual, it is rarely good. By individual I mean that every singer has a tone unto himself. It is as characteristic of her as are her features. As soon as she attempts to imitate some other tone she distorts her natural tone. The peculiarities of mouth and throat formation which she possesses are identical with those of no other singer. The most she can do is to develop her natural tone to its fullest extent. The wise singing teacher often discovers that the tone that a pupil is employing is not the natural but an affected tone, brought about by environment or imitation. It then becomes the teacher’s duty to restore the natural quality. Sometimes the teacher never does this, and the pupil only acquires a comprehension of her natural tone after much self-investigation, deep thought and experiment.

Imitation is sometimes of assistance in discovering the means by which the tone may be delivered with the most ease and effect, but imitation is not always to be desired. Some years ago a noted English singer and the author of a treatise upon singing asked me to imitate his methods. I realized at once that while they might be successful with him they would certainly not be successful with me. He has been obliged to discontinue his work, and a mistake in his conception of tone production has cost the public one of its best artists.

No amount of imitation could ever make a robin sing like a nightingale, because the robin was never intended to sing like a nightingale. The song of both is beautiful, but individual. Investigate ceaselessly to find out the real truth about your voice. This was what Patti did in her girlhood, and her voice has lasted for a phenomenal length of time. Most singers lose their voices because they sing not in the manner in which God and Nature intended them to, but in the way that someone has told them.

The thing that really thrills an audience, that goes up and down their vertebræ, that makes them respond with unanimous applause, is the bond of musical sympathy which the singer must invariably arouse to reach great success. It is the soul of the singer—that wonderful something which will leave the body after dissolution. Mental and physical endeavor will not avail; it is that intangible substance which keeps us alive and which reaches out to the audience and makes them one with you. When a beautiful soul expresses itself through a beautiful voice, no audience can withstand the charm. Better the singer with soul and a beautiful, natural, individual voice than all the technique, execution and “interpretation” in the world. We must study art to know how, but only too often this very so-called art simply means a collection of unnatural and artificial encumbrances which retard the singer in the fulfillment of the ideal.

SUSTAINED TONES.

From the art side, the first consideration is that of learning to acquire and sustain a good tone in what might be termed an even vocal stream. The regulation and adjustment of the breath has much to do with this. It is wrong for the young singer to attempt to sustain tones too long at the outset.

Long-sustained tones impose a strain, and all strain is ruinous in the end. Sustained tones should be practiced softly at first, and then they may be gradually sung with increasing force. This may be followed with the crescendo and diminuendo until the singer has her voice under such control that she may start with a mere thread of a tone and expand it to one of considerable volume. This, of course, requires practice in itself, and all practice must of necessity be more or less mechanical. Therefore, we should never forget the words of Jenny Lind: “Singing is as much moral and mental as it is mechanical. It is a combination of those qualities which alone can form the master and the pupil.”

It should be remembered that Jenny Lind was faultily taught at the beginning, and when she went to Garcia, in Paris, in 1841, he told her that it was useless to try to do anything with her, as she had lost her voice. She begged for a trial, and he consented, provided she would agree to refrain from singing or speaking for six weeks. This she did, and surely after such a period of enforced silence a woman should deserve all the success that was hers in after-life. However, while she was not singing or speaking, she was studying French and Italian, as she knew that she would require these languages in later life. When she commenced her work again with Garcia she describes his methods in her own words thus:

“I have already had five lessons from Signor Garcia, the brother of Mme. Malibran. I have to begin again from the beginning to sing scales up and down, slowly with great care, then to practice the shake awfully slowly and to try to get rid of the hoarseness if possible. Moreover, he is very particular about the breathing. I trust I have made a very happy choice.”

Jenny Lind always recognized Garcia’s great ability, but in a later letter she writes in a manner corroborating all that I have said about self-investigation and personal experiment:

“The greater part of what I can do in my art I have myself acquired by incredible labor, in spite of astonishing difficulties. By Garcia alone have I been taught some few important things. God had so plainly indicated within me what I had to study; my ideal was and is so high, that I could find no mortal who could in the least satisfy my demands. Therefore, I sing after no one’s method—only, as far as I am able, after that of the birds; for their Master was the only one who came up to my demands for truth, clearness and expression.”

What a remarkable definition of the requirements of the singer! Perhaps it was thoughts like these which led the public to call her a “nightingale.”

PITCH AND CORRECT INTONATION.

I often think that what the public describes as a “musical” voice is nothing more than that of the singer who sings with correct pitch. It is unfortunate but true that very few singers sing at all times exactly on the key. Instead of striking the tone directly in the heart, as it were, they seem to hit around it.

Every tone has a heart. That is, there is one vibration at which the tone is right. Let us say that the middle A is given a vibration of 435 double “swayings” to a second. If one should sing this tone at 430 or 432 the difference might be slight and one that few people would recognize, but they would note a general difference in the singing and would be very likely to say that the singer was singing unmusically or that the voice was not musical.

Students cannot give too much attention to the matter of pitch. Sometimes the physical conditions of the throat and nasal passages caused by a cold or by fleshy growths, such as adenoids, will cause the singer to sing “off the key.” Similarly any unnatural tightening of the tongue or muscles of the larynx may lead to bad intonation. A bad administration of the breath may lead to a like result. In most cases, however, singing with uncertain pitch is due to carelessness in failing to listen to the tones acutely enough.

Personally I found the violin of immense help to me in establishing a correct idea of intonation. Up to my fifteenth year my parents desired to have me become a virtuoso violinist and I studied and played a great deal upon the instrument. This taught me the necessity for striking right into the heart of the tone. “Singing off the key” is extremely annoying to me and I find it difficult to sing with singers who are unfortunately guilty of this fault. Some never can correct it. Years ago, when I was studying with the great dramatic soprano, Mme. Fursch-Madi, she told me of a girl with a marvelous voice who had failed dismally because she could not keep on the key or rather sing with accurate intonation.

The slightest difference in pitch becomes perceptible to the singer.

IMPROVING THE QUALITY.

It is almost always possible to improve the quality of the tone. At first the student will find that her difficulty lies in the matter of keeping the muscles of the throat and mouth sufficiently relaxed. The knack of placing the tones in (“from out the mask,” as the French call it), is one which is difficult to acquire. This the teacher must explain and illustrate. It is a well-known fact that in smiling the voice becomes brighter and seems to be placed more forward. Jenny Lind always insisted that the singer must, above all things, “look pleasant,” and that in this way the tone would be improved. She was also opposed to the grimaces that singers were wont to make. In smiling the muscles are all loosened and the upper lip is elevated a trifle. Of course, the student must avoid anything approaching a broad smile.

REALLY BEAUTIFUL NATURAL VOICE IS RARE.

The gift of a beautiful voice is a precious one. Few possess it and yet many of those who do possess excellent voices do not take the pains to develop themselves so that the voice may be of the greatest service. The mere possession of a beautiful voice means nothing. The great singer is to be praised for whatever she may have accomplished with her voice and not for the mere gift of the voice itself.

We continually hear the voice described as a delicate organ. To me it seems the hardiest organ we have. When we remember that it is used from the earliest infancy to the very last breath in old age, and that it frequently exists after all the organs have wasted away, we can realize how strong the vocal apparatus really is. In most cases the voice is horribly abused throughout life, it must be tough indeed to have withstood the monstrous vocal methods I have heard practiced in some cases. However, continual colds and malusage of the throat bring their punishment in time, and when the voice is once gone it is extremely difficult to restore.

Beautiful voices are like roses in June, here for a little while and then forever departed. Perhaps we should be grateful for the modern means of preserving voices through sound-recording and reproducing machines. What would it mean to us to-day to hear just how Mario, Malibran or Jenny Lind sang. I believe that records of the voices of great singers of our own time will become rare in the future and that these records will therefore be highly valued and prized as family heirlooms along with choice paintings and the family plate as evidences of the culture of one’s ancestors.

COLD AND LIFELESS VOICES.

The singer with the cold or lifeless voice rarely succeeds. The voice of even the dramatic singer performing in the heaviest Wagnerian roles must possess elasticity and flexibility to appeal to the public. There is a reason for scales and exercises like those of Concone and Bordogni entirely apart from the commonly accepted idea that they are solely preparatory exercises for coloratura or fioratura singing. It should be remembered that many of our greatest Wagnerian sopranos have been coloratura singers in their younger days. Depth and breadth of tone come with age.

If a singer desires to retain the brightness and vitality of a youthful color in the voice, the sparkle and the wine that invigorates and stimulates, the exercises for flexibility should be constantly practiced. It is also an excellent idea to practice upon the vowel “u,” as in the French word “Etude” or in the German word “Brüder.” This vowel is somewhat difficult to acquire. It is really a mixture of e and u. If you will shape your mouth as if you were going to pronounce “U” and then hold it lightly in that position while you say “ee” the tone will approximate that desired, but you should hear it repeatedly pronounced by a native Frenchman in order to hear it correctly. If not overused this vowel seems to have a corrective effect for dull or heavy voices. It seems to throw the tone higher and more forward in its passage outward.

THE OBNOXIOUS TREMOLO.

In America the tremolo is gradually passing and it is to be hoped that in future years we shall hear but little of it. In fact, in many cases it has been so bad that it has almost amounted to what might be called a trill. It is to be remedied first by breath control and then by mind control. After the teacher is assured that the pupil possesses a steady, even flow of breath a tremolo may sometimes be cured by having the pupil speak the word to be sung and then calling the pupil’s attention to the fact that a tremolo is unnecessary in speech and may be avoided in singing if the pupil only pronounces the word in singing as she does in speaking. This is a simple method, but very efficacious if properly applied. Some singers, however, desire to have a tremolo. By whatever criterion they judge tone I certainly do not know. To me a tremolo is very offensive.

MAKE A THOROUGH STUDY OF MUSIC.

I have mentioned the benefits that I have derived from the study of the violin. Unfortunately I was unable to give similar study to the piano. My teacher in Paris, M. Bouhy, for some unknown reason, objected to my taking up the study of the piano as a side study. He doubtless wanted me to concentrate my attention upon voice study. However, I have always felt the necessity for pianoforte so keenly that during the last six months I have taken up the study of the instrument myself. It opens up wide vistas for harmonic understanding and enables the voice students to comprehend the entire scope of an important work at first hand. Of course, I have always played piano to a certain extent, but I have never studied the instrument seriously until now. I have always desired to improve continually and this is simply a part of my regular daily study which will continue as long as I am before the public.

In studying the rôles of important works I have avoided voice fatigue by playing the soprano parts upon the piano with my accompanist in duet fashion. I rarely sing a new rôle until I feel that I have mastered the time, rhythm and notes. This I find also contributes to accuracy and confidence. The amount of study required to master a new rôle is far greater than many people imagine.

No matter how great the artist or how extensively she has appeared before audiences, she can only maintain her position by ceaseless study. To use the voice for more than a small portion of the time would be disadvantageous, consequently the piano is of immense value to the singer. It is far better to work out the problems of a new work oneself than to have it done by someone else. First secure a good tone, then flexibility and execution, and then consider the interpretative side from the intellectual and spiritual standpoints.