By WILLIAM ARMSTRONG

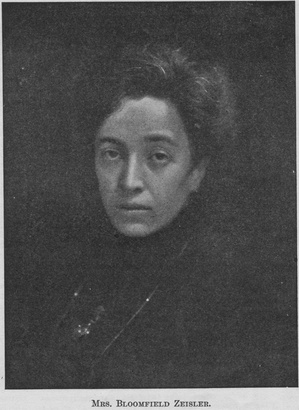

It was at the Holland House, just after her single New York recital this season, that Mrs. Bloomfield Zeisler (she prefers the less pretentious title to Madame) talked to me for The Etude on the literature of the piano and its study.

She is a charming personality, complex, perhaps contradictory, to be more exact. Thoroughly womanly, sensitive beyond the understanding of persons less finely developed, with profound love of home and all the word conveys to a devoted wife and mother. And it is just at this point that the contradictory, so to speak, in her nature is developed. Her love of her art is so absorbing that there is a continuous struggle between it and her deep womanly instincts. She leaves her roof-tree with reluctant heart to carry the battle into distant lands and after triumphant success returns in a passion of tears over the greater joys of homecoming.

In years past, when she lived just across the way from me in Chicago, I have known her to catch the first train after the final concert of an exhausting tour, and journey day and night with only one thought in mind, to be with her family, and that as quickly as the fastest express could carry her. Her art compels her to these journeys: London, Berlin, Paris, or the other end of America. All the while her heart is in her home, and she is longing passionately to get back to it.

In years past, when she lived just across the way from me in Chicago, I have known her to catch the first train after the final concert of an exhausting tour, and journey day and night with only one thought in mind, to be with her family, and that as quickly as the fastest express could carry her. Her art compels her to these journeys: London, Berlin, Paris, or the other end of America. All the while her heart is in her home, and she is longing passionately to get back to it.

In the midst of her first great successes in Berlin she would sit and weep over the letters that her little son wrote her, and rebel against those same successes that kept her from him. The moment that her duty to her art was over she was on her way back to America, returning in delighted tears. In such moments you would feel that she would surely never get up the courage to face separation from home ties again. But, in a few months, the art spirit impelling her, she would be on tour once more. Contradictory did I say? No, it is not contradictory. It is, after all, only an illustration of the very strong, genuine, sympathetic, and emotional qualities that charm us in her playing.

For five years I had not seen her until the other day, for when she had been professionally engaged on one side of the world I had been taking a trip with my lead pencil on the other. But there she was, the same unchanged, slender woman, with the same nervous strength that carries her farther than an iron physique would another. There was the same frank sincerity and genuineness in conversation and manner and the same changing, transparent emotion expressed in her face.

The Study of Mozart and Chopin.

“Is the study of Mozart a good prelude to the study of Chopin?” she repeated presently, turning from personalities to the practical subject of the moment. “The study of Mozart is good at any time, but not early in the pianistic life, for he is one of the most difficult of composers to play rightly. The paraphernalia of the modern pianist cannot be applied to his performance. For that very reason the Liszt player may not be able to play Mozart. The simplicity and purity required in Mozart, foreign to the decadent moderns, shows every flaw in the playing of it. To play Mozart you must not be sentimental, and you dare not be tiresome. To find the exact measure or balance is no easy matter.

“There is just one point in which Chopin and Mozart meet in the matter of performance, and that is in the purity and delicacy demanded by both. Yet I would rather trust some Chopin things with a lesser player than I would care to risk Mozart.

“Mozart is so seldom played that if one should begin to enumerate the works of his that are not often heard one would have to enumerate almost everything. Beyond the A Minor Rondo scarcely anything of his is given nowadays. People seem to have lost that simplicity of feeling and thought necessary to his interpretation, and they have not the right kind of technic either.

Some Recommended Compositions by Mozart.

“The compositions by him that I would call to the attention of the student, now that you ask me, are: the sonata in F major; the one in A major, with the Turkish March,’ and the beautiful C minor ‘Fantaisie’; and of the concertos, the one in E-flat, and also the D minor. He has written many beautiful smaller things, too, that are a delight to the pianist.

“Grieg is a composer, as you know, that I play a great deal—his ‘Ballade,’ for instance, which I regard as his greatest work for the instrument, and I love his concerto. His ‘Sonata’ is very interesting, but it does not show him quite at his best. Then, too, there is his ‘Holberg Suite’ in pianoforte arrangement, which is very good and not too difficult.

“Grieg’s fame rests on his smaller things, of which he has written so many within reach of the general player, lyric pieces, exquisite in their local color, and full of delicacy. I am fond, too, of his piano and violin sonatas. The one in F major is popular, but not so great as the C minor.

“What I admire about Grieg, the composer and the man, is his sincerity. I know that he has been criticized for his Norwegian color, but it is natural for him to have it. He is only true to himself in giving it, and he would not be the man he is if he did not. He is so honest and so sincere.

Works by Modern Composers.

“As to pieces by modern composers who are not played generally by pianists, I try to include a few in each of my recital programs. And I have generally found that the audience is with me. One cannot please everybody, and the sensitive may demand only the giants among composers. But in the olden days of Chopin and Schumann— and we know what a hard time the latter had in gaining a hearing—when they were in their beginnings, if all had been of the ultra-conservative type as far as recognition went, what encouragement would they have had to higher flights?

“I have always tried, in selecting these newer things for performance, to seek out men who have possibilities. You may find many pretty things, even if they are not great. Those same composers may develop. Somebody must give them a hearing to help in that development.

“I have found that devoting ten or fifteen minutes to their compositions is refreshing, and makes us enjoy the giant things more that follow. The menu of a dinner cannot be all soup and beefsteak. There must also be some light little things, and a musical program must have the same characteristics. They are as correct in this case as in that of the menu. Schütt, Poldini, Moszkowski, Godard, Chabrier have given us some charming examples of modern, lighter work. Poldini, for instance, a pupil in piano playing of Rosenthal, and now living in Switzerland, has written among other things little sets of four or five pieces that are very attractive.

Whenever my pupils have studied one of his compositions they have invariably gone in search of more of them. A set of etudes are among his more ambitious achievements. This season I am playing a few things by living pianists. And why should I not? If they are not as great as the Beethoven symphonies, they are written well for the piano; the public likes them, and so do I. I am not averse to paying a compliment to a colleague who deserves it.

Russian Composers.

“What have I to say of the Russian composers for the piano? They have written some beautiful things, and in mention of them we must not forget Rubinstein, for I suppose we should regard him as a Russian. Tschaikowsky’s compositions I love. If his nobler examples are in orchestral forms, he has also given us one of the most beautiful piano concertos written for the instrument, and his ‘Variations’ are fine. I recall, too, smaller pieces: a Nocturne, a Bacarolle, (sic) and also ‘Die Jahreszeiten’ (‘The Seasons’), among his smaller admirable compositions for the instrument. The only trouble is that life is too short, there is not time enough to play all the beautiful things.

How to Study a New Work.

“When I have studied a composition I never play it in public at once, a plan, I think, that most pianists unfailingly follow. It is wiser to put a work aside to ripen, as it were, and then to finish it up.

“Do all you can with a piece the first time of study, then put it away, forget it. Certain points that you have gotten fidgety and nervous over you will meet in a fresh, neutral state of mind when you take it up again. It sinks in and becomes a part of yourself.

Some Notes on Practice.

“Do I think it best for the student to have a fixed time for practice, and to stick to it? I do. I will tell you for what reason.

“In itself the having of a fixed hour is not so essential, but if you have no settled system other things invariably interfere, especially in a large city, where there are so many counter distractions. The morning is the best time for study, for one is then refreshed from sleep and the nerves are in better condition. As to the length of time to be devoted to practice by the serious student, I am not speaking now of the professional pianist, I should say four hours is not too much. If you are very strong and very enthusiastic, five hours, if the mind is fresh, but no more. But to get through that fifth hour the mind must be fresh. The moving of the fingers is not practicing, for in piano work the fingers accomplish one-fourth, and the brain three-fourths of the result. If the brain is tired it is worse than useless to attempt further work. One cannot figure it out mathematically, this approximate comparison of mind and brain in the right kind of piano practice, but I think the estimate about correct.

Some Notes on Teaching.

“I could not explain how I teach unless I actually taught, it is a something requiring practical application to make practical explanation. Personal contact is of so much importance in the matter that it could not be otherwise. Character, temperament, the stage of advancement are all among the factors to be considered. Do you know why so many Leschetizky pupils have each a different manner of playing? He has treated each one of them as individuals. This you may correctly term the Leschetizky method of teaching that particular one. Take, for instance, a pupil who is phlegmatic and slow; when the housecleaning, so to speak, of technical acquirement is over, he sets about the development of rhythm, life, and temperament. Again, in case of one of opposite and fly-away traits he follows with them the study of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms. Each temperament and individuality is different, and each is treated accordingly.

“For that reason it cannot be said that a Leschetizky or any other great teacher has a method, except as far as appertains to strictly technical things. There can be no methods in any but that sense, for the term is leveling. The purely technical equipment is common to all in its application and achievement.

“That which in reality is the Leschetizky method is the development of temperament and personality in interpretation.

Overcoming.

“What is the best way to fight discouragment? (sic) The mere fact that a pupil is discouraged is no real reason that discouragement should exist. For the matter of that there is no great musician who has not had days, weeks, and months of discouragement.”