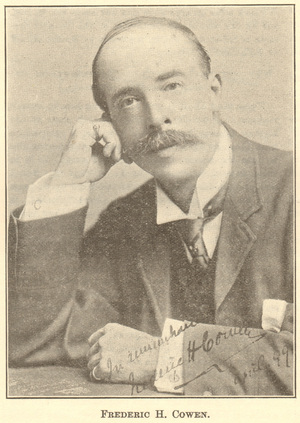

DR. FREDERIC H. COWEN, the busiest conductor in England, is an interesting personality. He has the same restraint of manner that distinguishes many of his countrymen, yet much enthusiasm and a marked gift of fluency of speech, directly and simply expressed.

It is always interesting to hear a busy man’s reasons for his ability to withstand fatigue. Dr. Cowen, certainly one of the busiest musicians imaginable, attributes his powers of recuperation to an ability to sleep whenever the moment presents itself, instead of giving way to the strain of nervous anxiety. He is conductor of three orchestras: the London Philharmonic, the Liverpool Orchestra, and the Scottish Orchestra; two choral societies at Bradford, and the Festivals of Scarboro, Cardiff, and a number of isolated concerts besides. The details of these organizations, in which he is consulted by the various committees; the making of over a hundred programs annually, and the amount of travel to and fro constitute in themselves an exacting task. Beyond these things is the strain of rehearsal and public performance, when the fullest response of vitality is demanded. Still, he finds time for composition, his latest accomplishment in this direction being a Coronation Ode, written by Royal command for performance at the first state concert this year at Buckingham Palace.

In a conversation one rainy morning last summer, which meant almost total absence of sunshine in London, Dr. Cowen touched upon the selection of words for song and cantata setting, the change in oratorio style, and the influence of a great individuality upon the composers that follow him.

In a conversation one rainy morning last summer, which meant almost total absence of sunshine in London, Dr. Cowen touched upon the selection of words for song and cantata setting, the change in oratorio style, and the influence of a great individuality upon the composers that follow him.“The better the poem,” he said, “the better the song. What I do think is that the best words for musical setting are those which convey simply an idea, nothing more. As to the length, to my way of thinking they should never be longer than two or three verses. In looking for words for song-settings I try to follow a broad plan of reading, books of poems, magazines, and general sources. The words for ‘Light in Darkness’ I found in one of the religious journals. Comparatively unknown poets have written some very beautiful things for musical setting, as, for instance, Marston.

“The words of my seventy or eighty songs, though, are nearly all by standard poets, Rossetti, Swinburne, and the rest. Of those by the old English writers I have used only a few; they do not go well with modern music, and always seem to yearn for an old setting, which I have endeavored to give to those I have chosen. For the reason that I think a song should not be longer than two or three verses, I have taken the liberty of cutting poems. Of course one must be most careful in doing this. In Adelaide Proctor’s poem, which I used for my song ‘Because,’ there are twelve or fourteen verses. I used only two of them, the first and last. These sustained the idea, unity, and completeness.

“If you get hold of a musical poet, I do not consider English unmusical or unvocal. But a great deal is in the poet himself; it means much if he be a poet in words. Browning, for instance, is unmusical; Longfellow exceedingly musical. There is one drawback in English, the comparative lack of open sounds; but even then you get the broad a in father, etc., etc.

“As to the words for cantata setting, they appear all to have been exhausted. Very few can write them, for there is lack of musical inspiration. The writer of a book for either cantata or opera must have intuition of what is required in music; many have not got that at all.

“The days of absolute oratorio are numbered. People want the dramatic form on scriptural or sacred subjects. Now modern oratorio, but oratorio as we know it, ended with ‘Elijah.’ I never look on that work as an oratorio, but a biblical opera. There is nothing sacred in the strict sense in the subject, it is simply the history of a prophet and the pagans. The public of to-day want a human story. They want human interest on the concert platform the same as on the stage.

“In the repetition of subjects for oratorio there is one great exception. No matter how often the story of the Saviour has been written, it will always be acceptable to the world at large if it is well done. It is difficult to follow Handel’s ‘Messiah’; but if someone would set it again in modern oratorio as we know it, and ably fulfill his task, its acceptance would be assured.

“It is always the misfortune of a great personality to be copied. The more mannerisms a composer has in his style, the more likely he is to find imitators. Beethoven had no imitators, he was followed, not copied to the letter; but he had no mannerisms. Wagner continued the development of the orchestra which Beethoven, Weber, Meyerbeer, and Berlioz began. Yet anyone who employs full orchestra is called Wagnerian—by idiots.

“Another instance of tremendously strong personality is Tschaikowsky. Everyone is influenced more or less by his works; they cannot help it. When I met him first he was little known. He appeared morbid, but in company was most genial. The majority of persons, whether artists or not, have a dual nature; one that they live to themselves and one that they show to the world. The artist’s half-life is passed within himself, when he goes out he shakes it off.

“The real musician has a very impressionable nature, he is influenced by everything outward. In my experience I have been thrown with many artists of the opera. There is an immense amount of the child in him; he is very easily amused. This trait remains with him throughout his life, and in a way is his salvation and source of perpetual youth.”

Any chronicle from London, no matter how brief, would be incomplete without some mention of Dr. Edwin Elgar. Both in England and Germany the degree of attention that he is commanding is very great. In the latter country they claim a wider recognition of his abilities than is granted even in his native land, and the reception of his orchestral works has been marked by an enthusiasm never given there before in the instance of an English composer. Dr. Elgar occupies a unique place for any man to hold in any profession. The first among his colleagues has frankly said at one time or another: “He is our greatest.”

“You seem,” I said to him on our meeting, “to be the son so long hoped for and at last arrived.”

His answer was a quiet smile with a touch of gratification in it. Of words he is chary except in the discussion of his art or general and abstract subjects. That which he does say of himself becomes the more interesting, however, through the fact that he is entirely self-taught, and has developed himself musically and intellectually away from those centers where the student congregates. Musically he is self-made. A deep thinker, he states his ideas frankly. A tall, broad-shouldered man, with dark, frank eyes, dark-brown hair, slightly silvered at the temples, although he is still in early life, his manner is genuine and straightforward. His face is that of a literary man rather than of a musician.

The first subject that he hit upon was: “how to smoke a pipe,” and it was not until I knew that the real luxury of such a proceeding was to take from three-quarters to an hour to a single bowl-full that we got down to music.

“No, I belong to no school,” he said presently, “for I am self-taught, and so I admire them all for the

good that there is in them. If I were asked, perhaps, who comes first with me I should say Mozart. I love

his music. As a boy I studied it devotedly. To-day I have his bust on my study-wall.

“The impression made upon me by Beethoven’s First Symphony I shall never forget. There was a big family of us, eight children in all, and it was a hard thing for me to get a quiet place to study in. We lived at Worcester, where my father had a music-shop. When I was allowed this score in particular to look over I locked myself up in the bath-room, the only really secluded spot I could get. The first and second movements did not impress me so forcibly, but when I got to the Scherzo a new world seemed opened out to me.

“The only lessons that I ever had in music were a few on the violin, which is my instrument. Through my father’s business I had access to a great deal of music, and studied and read all the books that I could get bearing on the subject, and, of course, on harmony and composition. I was intended for the law, but music held me.

“I began, I think, at what people would call the wrong end—the old Italian opera. My father being organist in the Catholic Church at Worcester, and many of the opera-singers visiting there being of that denomination, I heard them sing solos at the services, and on week-days was given a place down in the orchestra, where I heard the operas of the old Italian repertory. It had been promised me that I should go to Leipsic to study, but when I was about fourteen my father explained to me that things had not gone very well, and that the undertaking would be impossible. How heartily glad I am of it now that I did not go, but studied on untrammeled, free from foreign influences in the dominant sense!

“By and by, through teaching, I saved up seven pounds, and announced my intention of going to London to study. I took a little room down in Victoria at eight shillings a week and went to the violin master, Pallitzer. Under him I had five lessons, studying eagerly, as may be imagined, and then back to Worcester. I have kept away from London, living in the country, at Malvern now, where I do my composing in a cottage some distance from the house, hemmed in by trees, and away from the world.

“Many say that Englishmen are not romantic. With that I disagree. There is a vast difference between sentimentality and romance. Perhaps things in London impress me more strongly than they do those who live there constantly, but, when I go into the Guildhall, the center of the civic life, as it were, and see what has been done and the records and inscriptions of those things, the spirit of them impresses me very deeply. It is something of this spirit, and of the underlying jovialty as well, that I have sought to convey in my overture ‘Cockaigne.’

“The demand for choral works has caused very many to be written here in England, but too often, perhaps, with a regard for the mass of sound rather than for color, for many choruses like a good shout, especially in the north of England—but how well they sing! My idea in writing for chorus is that, while I regard four-part writing as the backbone, the voices should be divided into eight and sixteen parts, and again alotted to double chorus, trios, and so on. Then it is that value, contrast, and the color-effects of which massed voices are capable may be properly obtained.

“As to the ‘reading’ of scores which we hear discussed so much to-day I think that the broad outline is too frequently lost through a desire for infinite detail. The other day in passing out of Queen’s Hall I heard a group of young men discussing how this conductor and that read a certain passage. But did they know the composition itself? Perhaps so, but I fear not. And after all it is the composition itself, the whole broad outline, that is of the first importance for us to know.”