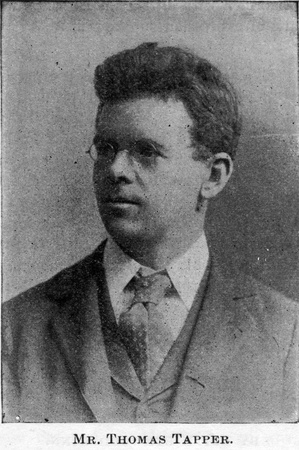

Mr. Tapper was born at Canton, Mass., in 1864. After completing the high school course he commenced the serious study of music. For five years he was a student with Mr. Carlyle Petersilea and the late Mr. Lavallée. Mr. Tapper has been identified with the American College of Musicians from its inception, and has been an examiner in theory the whole time. The many-sided studies of this ambitious and thoughtful young artist are illustrated again in the various trips he has made to Europe. His first excursion of this kind was made in 1890. In 1892 he went abroad to collect material apropos to the Natural Music Course (of Public School Music), of which he is joint author with Mr. F. H. Ripley. In 1893 he went again, and had many consultations with musical educators, visiting schools, etc. This led him in 1895 to devote an entire year to study abroad. Residing most of the time in Vienna, he studied mainly opera and drama; and incidentally collected a vast lot of material for a bibliography of part-music. Mr. Tapper has been a successful writer upon musical subjects, and always along lines of his own. His first book was “Chats with Music Students,” in 1892; his second, “The Music Life and How to Succeed in It,” 1892. He has also written three books for children, called “Music Talks with Children,” “The Child’s Music World,” a book about music history, and “Pictures from the Lives of the Great Composers.” Mr. Tapper lives in Boston.

The fundamental conditions which govern Success in Music Teaching must be those which govern Success in anything else. This fact is based on the simple truth that we are, to a greater degree than we commonly believe, architects of our own fortunes. Success has to do with some simple principles which are clearly related, logically connected, and each, of itself, a unit of importance. But in speaking of Success we must remember that it is a purely-relative matter. In entertaining hope of it we are apt neither to define it nor even to scrutinize it closely. And yet we are constantly observing that yesterday’s Success is but the point of departure for what we would do to-day; and that the Success of to-day will be similarly fundamental to the strivings of to-morrow. Hence, it never rests, but entices us on; and we find satisfaction in appearing to gain that which we are perpetually pursuing. But one day there comes the thought that all our haste and pursuit is secondary to other qualities with which we have made slight acquaintance on the way. Had we thought upon them they would have given reality to our zeal, and we should have clung to that reality even as we plucked the smaller fruits.

To illustrate, let us set out with the Young Man on the day when he decides that he is ready to begin Music Teaching. What may we say to him that will put his thoughts to work in a healthy way?

I. The Personal Equation.

The Young Man is what he is by virtue of circumstances which are to a great degree inexplicable. His inherent character, the thoughts he permits himself to think when alone, his secret desires, and his professed ambitions spring from him as naturally as certain flowers spring from certain soils. His character is forever establishing a relation with his environment which he may study to his lasting gain. By the one he must interpret the other, recognizing the fact that change in environment follows upon change in character. This is so simple that he is apt to misinterpret it; the change is not so much in material things as it is in his altered power to interpret the environment. To be active, to think healthy thoughts, and to read one’s environment ever more and more spiritually is to have founded Success as the wise man founded his house; not upon sands, but upon a rock.

II. Education.

The inherent personal power is educated as a part of its experience. This means that it seeks, by following a definite course of thought and action in impressionable years, to train itself for wider circles of action, as well as for action that is definite. It strives to turn the personal power where it may expend itself to the greatest advantage. Our Young Man must remember that Education is not the fundamental quality with which he deals. He himself is that fundamental quality. Education is the process that defines him and emphasizes him. It does not make him so much as it intensifies him. It is the process which aims to direct the force divinely implanted in him.

III. Education Applied.

Having passed through his years of training (which some still call humorously “finishing his education”), the Young Man wants to get to work. The possibilities lying back of this desire are more diversified in nothing else than in Music Teaching. They range all the way from securing a place in a school at a good salary to guarding a lonely and unsought “studio” in the corner of the front parlor. But on whatever plane the Young Man finds himself, he must, as an individual, be busy. There are no end of tasks he may do. This is his salvation at all times.

At the moment of becoming his own master he must be warned of an error that is made by ninety per cent. of his class, the result being that they become hopelessly lost. That error is this: he must never believe that anyone puts faith in his protestations. The world, it is said, does not observe us as units. Our Young Man will discover that it is only because he is observed as a unit that he is professionally possible. And he is observed closely; judged not by what he says but by what he is; not by what he professes but by what he accomplishes. Failing to see it thus, he is forever out of tune with his possibilities.

IV. Geography.

While the years are passing on and the Young Man is doing that earnest and long-continued study necessary to the making of a Teacher of Music, someone is apt to drop the remark that the process is expensive. It certainly is; and not only that, but it deserves a better fate than often befalls it.

We are not unaccustomed to see the would-be teacher hesitating between the small town, where recognition is quick, and the large city, where one has to battle even for a foot-hold. The choice belongs to the chooser, and he must not grumble at the natural conditions. Here, for instance, is Miss A. She lives in Homeborough. By hook or crook (which means often privation and hard labor) she has learned a little about music. Perhaps it cost her a hundred dollars. She has pupils and continues to push on. Miss B. is of the same town. But she studied in New York four years at an expense of four thousand dollars. She decides to teach in Homeborough, and she, too, gets pupils. But her pupils do not stand proportionately to those of Miss A. as four thousand to one hundred. She concludes hastily that if the rain does fall alike on the just and the unjust, Miss A. must have contrived to get under a water-spout. It is not so, however; Miss A. is a working factor like Miss B. and is participating in an honest shower. Miss B.’s philosophy is loose.

V. Temptation.

How shall he advertise his business? Shall he go into society? Shall he become interested in church- work? Shall he refuse to give little Mary Ellen lessons because she has only a cabinet organ on which to practice? Many of these queries will arise to irritate his expensively-educated mind. But they are queries which find their reply in spirit, and not in letter. When the Young Man’s fundamental intentions are clearly set forth in his own mind, affairs will appear simple. When he offers his services to the public, it may not respond promptly. But whatever he finds to do, however little may come to him, in the manner of his doing, and not in the thing itself, is his salvation. When a door is opened to him he must not be surprised to find the room full and several others coming in after. This unwillingness of the world to specialize him merely means that he must specialize himself. Constantly he will find in the affairs of his daily life that he is in his own hands. And as the years pass on and he succeeds he will find that to him Success is one thing, to those observing him it is ever another. He may think that gain and renown are success; ultimately he will believe that it is in becoming what is his best possibility. It is harsh judgment, but it is just.

Then the Young Man will say that the basis of his Success in Music Teaching, or in anything else, lies in his attitude toward life. If he is useful, and helpful; if he is a good object in the environment of others; if he regards human relation above gain; if he adds better thought to the world, he has Success. In short, he asks if his activity and influence are indispensable to the betterment of life. If they are, he is working on the true basis of Success; if not, no amount of riches, in things that he may gather about him, or of knowledge that he may gather within him, will stand for anything else than the badge of servitude to masters who are unworthy.