[For The Etude.]

BY R. DE ROODE.

There is hardly any teacher who has not found, after teaching a young pupil the scales for one octave, and commences with two or more octaves in extent, that everything has to be taught anew, chiefly passing the first finger under the fourth finger, and vice versa.

To obviate this, I have, for some years, taught beginners to play the scales without the use of the fifth finger, and have found very gratifying results.

The object of the writer of this article is to lighten the work of his co-laborers.

I do not believe an Instruction book indispensable, and am rather inclined to the opinion of Otto Singer, of Cincinnati, who says, “if you have a teacher, you need no instruction book.”

The first thing to be taught is the name of the keys; that a sharp is the first key to the right, a flat the first key to the left. A double sharp the second key to the right, and a double flat the second key to the left. Three notes to each white key, of which there are seven, make twenty-one. Two names for each of the five black keys make ten. Total, thirty-one notes used in our present notation. This is taught in the first lesson; I mention half-tones and whole tones later.

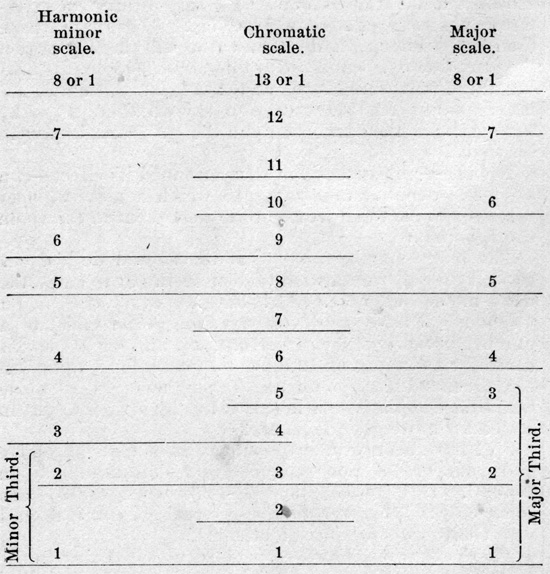

Next to be explained is the construction of the scale on the following diagram, making a ladder (scale) of 13 rounds, which is the chromatic scale, selecting therefrom 1-3-5-6-8-10-12-13 as the larger or major scale, and 1-3-4-6-8-9-12-13 as the smaller or minor scales. The pupil is then shown that the third actual note of a scale is its characteristic note, producing a larger or smaller interval as the scale is major or minor:—

A glance at this will show that the third and sixth are one key lower in a minor than in a major scale of the same name.

By this formula I require each pupil to pick out (using only one finger) the correct notes comprising each scale, both major and minor.

When fully acquainted with the construction of the various scales, and having drawn their attention to the fact that all scales have only seven different notes (the eighth being the same as the first), I tell them that in all scales the first, second and third fingers are used twice. This disposes of six notes. Hence, the fourth finger is used but once in each scale, and the fifth finger not at all.

Later on, permit them to use the fifth finger, when they realize that it is only a substitution for the first finger.

I reduce the use of the fourth finger to a few rules, which are required to be learned by heart. They were published once before, but I will here repeat them:—

RULES FOR RIGHT HAND FOURTH FINGER.

1. Whenever B flat or A sharp occurs in a major scale, the fourth finger comes on that key.

2. When B flat or A sharp does not occur in a major scale, the fourth finger comes on the seventh note.

RULES FOR LEFT HAND FOURTH FINGER.

1. Whenever the group of three black keys is used in any major scale, the fourth finger comes on F sharp or G flat.

2. In the major scales of B flat (2 flats), E flat (3 flats), and A flat (4 flats), the fourth finger comes on the fourth note.

3. In all other major scales, the fourth finger comes on the second note.

RULES FOR THE HARMONIC MINOR SCALES.

Every minor scale is fingered exactly as the major scale of the same name (not the relative), with the following exceptions:—

Right hand.—F sharp and C sharp when the fourth finger in minor comes on the second note in both scales.

Left hand.—B flat and E flat when the fourth finger in minor comes on G flat in both scales.

The above rules cover everything pertaining to scales.

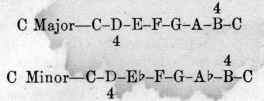

I require the pupil to write out all the scales in letters, as follows:—

Placing the fourth finger for the right hand above the proper note, and the fourth finger for the left hand below the proper note.

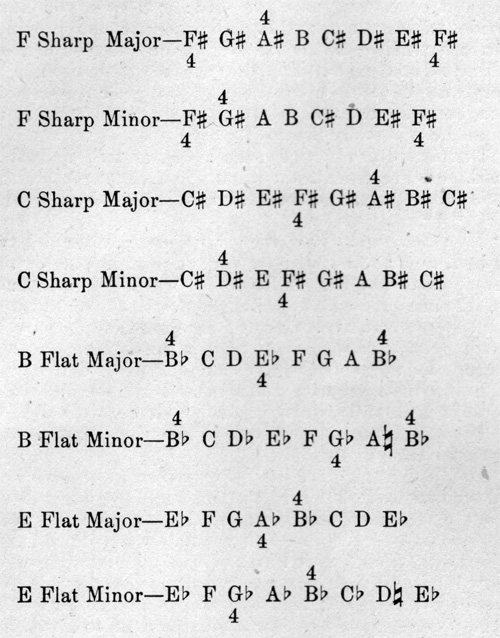

I append here the major and minor scales which were mentioned as forming exceptions—

It will be noticed that I use the fourth finger, right hand, on the first note in the scales of B flat (major and minor). I do this on the principle of using but one finger, unchangeably, for the same note in any scale.

When pupils can play one octave, they can play four octaves without additional work. It is quite amusing to see a little girl, seven or eight years old, without any notes before her, play twenty-four scales correctly. When playing the scale of C in the left hand the first finger is placed under the fourth finger, before commencing, and in this position she strikes C with the first, and D with the fourth finger. In the right hand she ends the scale in the same way, with the first finger.

The older I grow, the more I am impressed with the necessity of all pupils knowing all the scales, and playing them daily. As they grow in age and experience, any intelligent teacher can explain the same things in more technical terms; but every child can understand them by this system.

In memorizing the key of any given piece, the following system may be adopted. I require all pupils to remember by rote the order of sharps and flats in ascending and descending fifths—sharps, FCGDAEB; flats, B E A D G C F. Then tell them that the major key note in sharps is always a half tone above the last sharp, and the major key note in flats is the penultimate (or next to the last) flat. In five flats, the fourth flat is the key note. In three flats, the second and so on.

The minor (relative) key, with the same signature, is found a minor third (or three keys) below the major, and as all minors must have an accidental before the seventh note, tell them to look for that accidental chiefly in the left hand chords.

As a sample, take three sharps. Before permitting a pupil to answer, require her to ask herself the following questions: The major keynote in sharps must be a half tone above the last sharp. The order of three sharp is F C G. The last sharp is G sharp. A half-tone above is A. Should this piece be in a minor key it must be a minor third lower, which is F sharp minor, in which case its seventh note will be E sharp, said sharp not appearing in the signature, but being placed before every E as it occurs. She looks for that E sharp, and answers accordingly that the piece is in F sharp minor or in A major, and understands at once that whenever in such piece E ceases to be sharped, that portion of the piece must be in A major, or some other key other than F sharp minor, returning to that key on the recurrence of the E sharp.

For pupils sufficiently advanced to understand Elementary Algebra, I explain that sharps stand in the relation of plus signs (+), and flats in the relation of minor signs (—), and that the difference in the signature of major and minor keys of the same name is three, which amount subtracted from the major signature will give me the minor signature. F sharp major has six sharps, F sharp minor has three less, which is three sharps.

Taking number 5 of Mendelssohn’s Songs without words—commencing in three sharps and ending in six sharps—I make a pupil realize, without playing it, that there is no change of key, only a transition in character from F sharp minor to F sharp major, and that she must expect that the stormy, plaintive and restless character of the first part gradually brightens toward the end. The same with the same Composer’s Rondo Capriccioso, alternating between E major and E minor.

I realize day by day that even average pupils play far more intelligently by forming some conception of a piece before playing it.

Do not commence systematic scale practice until a pupil has reasonable use of her fingers by the preliminary five-finger exercises.

Also require all scales to be played in groups of two, three, four and six notes, properly accented, but always without printed notes. Later on, scales in thirds, sixths, tenths, contrary moods, etc., are added, and the melodic minor scales explained and added. But this takes time.

It will hardly be believed how few teachers there are nowadays that have a perfect command and knowledge of all the scales.

One more remark and I will close this, perhaps, too lengthy article. All the music people hear nowadays from brass bands, gospel hymns, dance music, is all in major keys. It is no wonder that the average girl cannot sing a minor scale, since she never hears it. A young lady who came to me for instruction, on being asked by me, if she knew what a minor key was, unhesitatingly replied, “Yes, everything that I don’t like, and does not sound right, is in minor keys.”

Our pupils hear plenty of music in major keys at any and all times; therefore I believe it to be the bounden duty of every good and progressive teacher, to use as much music in minor keys as he can possibly work in. It does more to build up a correct musical taste and eradicate preconceived erroneous notions than anything else.