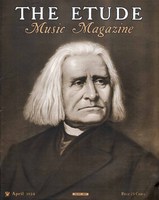

THE INDOMITABLE “PAT” WHOSE MASTERPIECE WAS PROBABLY “WHEN JOHNNY COMES MARCHING HOME”

By GEORGE R. LEIGHTON

The Story of One of the Most Picturesque Figures in American Musical History

Reprinted by Permission of “The American Mercury”

A HUNDRED red-shirted Boston firemen stand before a hundred anvils with a hundred hammers raised; a hundred comets glitter in the sunlight; two hundred fiddlers wait with bows poised; thousands of blue sashes rustle as thousands of New England sopranos rise, music in hand; in the distance the audience, thousands upon thousands upon thousands, banked tier on tier, leans forward in a hush of expectation, every eye fixed upon a man with glistening shirt front who stands alone on the high music-stand. The right hand goes up with a sharp gesture—there is a moment of vast and unearthly quiet—and then with a swoop the hand comes down. Thus the roar and boom of the Anvil Chorus break upon the audience, flooding the auditorium with a fury of sound. At the very height of the uproar the man on the music-stand signals a battery of cannon outside, and in that moment, through the smoke and thunder of the artillery, he becomes a name—Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore, first and greatest of American bandmasters.

He was only nineteen when, in 1849, he landed in Boston, a wild Irish boy from the town of Athlone. He was born at Ballygar, County Galway, on Christmas Day, 1829, and was named for the immortal General Patrick Sarsfield. Like so many other misguided Irish folk, his parents had hoped that he would take kindly to the church, but happily the snare was broken, and he escaped to a place with a merchant of Athlone. This garrison town on the River Shannon always had two or three regiments stationed in it, and without delay young Gilmore fell in love with their bands. One of the bandmasters, a man named Keating, took him in charge, taught him to play the cornet, and eventually placed him in one of the bands. Not long after this the regiment was transferred to Canada, and Gilmore, already becoming known as a cornetist, went along. Tiring of the service, he quit the British Army and set out for Boston, then the musical capital of the continent.

Army Discipline

HE FIRST found a place with the Messrs. Ordway, proprietors of a music store and of Ordway’s Minstrels, but shortly after that showed up in a Boston band. His extraordinary skill with the cornet soon brought him into notice, and from 1849 to 1856 he moved in quick succession from one band leadership to another. First he led a newly formed band in Charlestown and then he succeeded the famous Ned Kendall as leader of the Suffolk Band. An unremitting industry and an insistence on strict discipline—inheritances from his Army days—began to put a fine edge on his performances and his reputation bloomed. Then, not long before he took over the Boston Brigade Band, Louis Antoine Jullien, a popular French orchestral conductor of the time, with a passion for the sensational, reached America.

Jullien spread himself in red and gold stage properties, wore magnificent garb, used a jewelled baton, and rested between numbers in a golden throne. One of his most popular numbers, “The Firemen’s Quadrille,” included a display of fireworks at the climax, the appearance of a brigade of firemen, and the deluging of the aisles with real water. These strenuous monkeyshines made a profound impression on Gilmore, but what probably moved him most was the orchestra itself, one of the best that had ever visited America. Under the gaudy display and the tumult of the Jullien performances the young bandmaster saw his opportunity, and as early as 1869 he was feeling his way into Wagner.

Jullien sailed away to die, heartsick and broke, in a madhouse. Gilmore, then twenty-seven years old, quit the Boston Brigade in 1856 to lead the Salem Band for “a thousand a year and all he could make.” Within two years he was back in Boston and had organized his own band. In 1858 we hear of it for the first time. From then on, save for his term of service in the Union Army during the Civil War, he was its sole proprietor. His amiable temper and high spirits made him an attractive figure, and before long his acquaintances included many politicians, rich merchants and newspaper proprietors. With his insatiable appetite for and skill at advertisement, he used every possible means to attract attention. He took his band to the Charleston Convention in 1869, and then to Chicago for the Lincoln Convention in the Wigwam.

His band enlisted in a body with the 24th Massachusetts Volunteers in the Civil War, and its leader was promptly named Bandmaster-General and Chief Musician of the State of Massachusetts by Governor Andrew. The regiment was first ordered to North Carolina to accompany the Burnside expedition. It was a pretty tame show, and before anything much had happened the enlistment was up and the regiment was mustered out. Late in 1862 General Nat Banks succeeded Silver Spoons Butler in command of the Department of the Gulf and promptly put Gilmore in charge of all the military bands in the Department.

Just before the end of the war, he brought out When Johnny Comes Marching Home. It will probably never be known whether the pseudonym of Louis Lambert belonged to him or to another, but at all events he always claimed the air as his, and no one rose to deny him. Barely had the tune reached the country when the war was over. And with the homeward heroes, the colonels of twenty-six and the generals of thirty-four, came Gilmore, fired with ambition and sweating for new fields to conquer.

The Era of Jubilees

WE NOW approach what proved to be the climax of his career, the National Peace Jubilee held in Boston in June, 1869. Though thousands participated in it, it was his child, all, all his own, and he never quite touched the same height again. He got up another festival, even bigger, and yet a third, and for twenty

years after that was one of the leading bandmasters of the world; but the resplendent raptures of the first jubilee never came again.

What he proposed to do, he told the dazed newspaper men, was to erect a huge wooden structure that would seat 50,000 persons. He would then gather together choir singers by the thousands and form a stupendous chorus, assemble a band of a thousand instruments, and with this musical horde give a three-day festival.

Finding Boston cold, he tried New York. No luck again. Next he proposed to hold the festival in Washington to celebrate Grant’s inaugural, hoping thus to get some government backing. Still no luck. When at last the newly organized Grand Army of the republic refused to touch the scheme, Gilmore determined to swing it himself. He prepared a long and gaudy prospectus, written in his most splendid manner, and confided his copy to a printer sworn to secrecy.

Financial Support

THEN IN succession he won over Julius Eichberg, the director of the Boston Conservatory, and Carl Zerrahn, one of the best known orchestra leaders of the town.

THEN IN succession he won over Julius Eichberg, the director of the Boston Conservatory, and Carl Zerrahn, one of the best known orchestra leaders of the town.

Gilmore soon began to gather in some money. Ditson, the music publisher, and Mason, the organ builder, subscribed $1000 apiece. So did some of the hotel men of the town and a number of merchants. With this much backing—it was early in January, 1869—Gilmore bade the newspapers break the story. So completely stunned were the people of Boston that for several days there was almost complete silence.

Gilmore asked Dr. Upham, the chairman of the committee on music for the Boston public schools, for 20,000 school children, all to be trained under Eichberg’s supervision, to appear at one of the performances and sing popular melodies. He promised that a sufficient number of toilets would be provided in the coliseum for the young army and ended his letter praying that “the grace of God be with the undertaking and direct it to a successful end.” To organize the main chorus he enlisted Eben Tourjee of the New England Conservatory. Thousands of circulars were broadcast throughout the country, inviting every musical club and choral society in the land to participate. This first circular listed the numbers to be sung and gave the most detailed directions for rehearsal. Each society must report the exact number of its members and the distribution of the voices; evidence of the fitness of each local musical director had to be given. According to the circular, “the proportion which it is desired to establish is as follows: 8 sopranos, 7 altos, 5 tenors and 6 bassos; but the volume of tone in each of the parts must be as nearly equal as possible.” The circular wound up by offering a free bound copy of the festival music to every society, reasonable terms for lodging while in Boston, and half-fare railroad tickets, and assured all hands that the blessing of God rested upon the enterprise. In all, 103 societies from Maine to Illinois fell for the bait.

Hour of Darkness

AND THEN, after what had looked to be a running start, the supply of subscribers suddenly dried up, and, though Gilmore pleaded frantically, no more money was forthcoming. Worse still, those who disapproved of the scheme pitched on the festival with hammer and tongs. When the City Council gave permission to put the coliseum on the Common the Thayers, Coolidges and Higginsons screamed at the desecration. Gilmore, in agony, used every argument and blandishment in his arsenal; he declared that he was “prompted by higher and holier motives than mere worldly achievement”; that he was sustained by “the clear consciousness of being engaged in a great and good work—a work in the cause of music, of art, of pure patriotism and lofty virtues, of peace, of union and of religion.” But it was all to no avail.

Then, in his darkest hour, the rich and eminent Eben Jordan agreed to become treasurer of the undertaking, and all was well again. A National Peace Jubilee Association was organized to take over the management and the wheels began to move. To soothe the army of dissenters the Common was given up and St. James Park selected as the site of the temple of harmony. The Music Hall and other auditoriums resounded with the noise of rehearsals; every week the nearby choral societies came in to be plowed, harrowed and licked into shape. The indefatigable Tourjee rallied the distant ones, showing the Rossini Club of Damariscotta and the Harmonic Society of New Haven how to do their duty. Dodworth, the New York bandmaster, and George Lyon, of Lyon & Healy, both great friends of Gilmore’s, wrought valiantly in assembling the bandsmen, and Jim Fisk, the King of Erie, shamed the other railroad men by offering half-fares from anywhere. Through the noise and tumult thrashed Gilmore, every sense ravished by the most exquisite excitement. How he gloated when he reported that “over 2,500,000 feet of lumber” had arrived on the festival ground.

Mystery Lends a Hand

BY THE first of May every sort of rumor was afloat; it was whispered that the building was unsafe, that the vast galleries would buckle, that the audience of 30,000—if it ever came—would be trampled to death. Delicate Brahmins, alarmed by the prospect of so large a band and chorus performing in the neighborhood, prepared to move out of town. Gilmore found that the school board was afraid to trust 20,000 children in an untried building. With a flash of genius, he suggested that the children sing on the last day, after the building had been thoroughly tested by four performances.

At the last a momentous question arose. A soloist there must be. Yet whose voice could fill so huge a building ? The committee, after deep thought, fixed upon that gigantic, soft-hearted and bovine soprano, Euphrosyne Parepa-Rosa, the only singer who could possibly hope to meet the specifications. The kindly artiste accepted the invitation in a letter that fairly quivered with excitement, assuring the committee that “as to terms I leave them entirely to the committee, as no feeling except the pleasure of joining so great an undertaking can actuate any artist.”

In the midst of all this prodigious activity Gilmore found time to hunger for a new national anthem. He groaned at the thought of Longfellow absent in Europe, “shrinking like a timid bird from the homage that the high and humble alike would gladly bestow,” but decided to do what he could with Oliver Wendell Holmes. The bandmaster swooped down one morning on the doctor and his Irish flattery proved irresistible. Holmes fell over himself, and within a few days delivered a very dubious work entitled “A Hymn of Peace.” Meanwhile, the aged Edward Everett Hale agreed to invoke the blessing of the Most High at the first concert, and Lowell Mason, then doddering toward the grave, signified his willingness to attend as the guest of honor. By a stroke of Providence, Ole Bull showed up on a concert tour, and was panicked by Gilmore into accepting the post of first violin. Last of all, Grant and his Cabinet and a whole retinue of Army and Navy swells accepted invitations and Gilmore’s cup was full. There was, perhaps, one single regret. The bandmaster cabled to Johann Strauss, the Waltz King, begging him to come, but, alas, the Tsar had first choice and Strauss had gone off to St. Petersburg.

Not Quite the Biggest

THE EXCITEMENT of the last few days preceding the festival almost sent Boston into hysteria. A cough-drop manufacturer announced that he would present to each of the 10,000 choristers a box of Brown’s Bronchial Troches, and the largest bass drum ever constructed, twenty-five feet in circumference, arrived ostentatiously upon a flat car and was met by a crowd that jammed the station. The newspapers were prodigal with the space they gave to the affair—the Boston Herald using more than twenty columns in a single day— and, though the Saturday Evening Gazette regretted that the auditorium covered but four acres, whereas the Flavian ampitheatre had filled nearly six, still “that was the work of a rapacious and sanguinary despotism that plundered the whole world to execute its plans, whereas this is the work of free hearts and unbloody hands, and not a tear has fallen to water its growing.”

Prudent New Englanders were shocked almost beyond endurance by the news that $120,000 would be spent on the building alone, and that it would be torn down at once. The price of tickets was also staggering; season seats for three cost $100 apiece. The newspaper reporters measured the pipes of the largest organ ever built, and exulted in print over the coliseum’s retiring rooms, so “completely equipped for every necessity of nature.”

Came the day (June 15th) and the hour. One who sat in the rear of the balcony described how the floor slowly filled with spectators, and how it looked to see an endless procession of people streaming into the gallery seats that rose, rank by rank, from the floor up the sides of the building. Above, the rafters were draped with flags and banners, the huge beams gilded and bedaubed with patriotic sentiments. Over the stage rose a gigantic arch adorned with two monstrous angels gazing upward at the words which unrolled themselves in colossal letters : “Glory to God in the Highest; Peace on Earth Good Will Toward Men

Section by section, the choristers took their places while the band could be heard whining to itself as the instruments were tuned. Then, at three o’clock, the doors were shut and the aged Hale rose in the dim vastness of the hall to make his prayer. No one heard it.

First Carl Rosa, the concert-master, made his appearance. Applause! Then the white haired Ole Bulb. Prolonged applause! Last of all, Gilmore, the star-shaped studs in his shirt-bosom all gold and glitter, his sideburns and chin-tuft bristling, his whole body trembling with exultation. The applause shook the building. The bandmaster said something about his gratitude, lavished his appreciation on his executive committee, called on the audience to remember that “to One alone, the Omnipotent God, all honor, all glory and all praise are due,” and then turned to his band.

Came the Thunder

AT THAT precise moment—of course Gilmore would plan it so—there came a thunderclap like the last trump. Organ, orchestra and chorus, all together in one burst of fortissiino, broke into Ein Feste Burg. The effect was stupendous and when the ancient choral was over Gilmore knew that he had beaten his enemies to a pulp. The audience almost went crazy. Quivering with happiness, the bandmaster bowed before the tumult of applause and disappeared as Eichberg took up his baton and signalled for the “Tannhäuser” overture.

Through the long week the musical deluge went on. Grant came to be greeted with See the Conquering Hero Comes done with such brass and thunder as had never been heard before. Gilmore had to give up his cherished hope, of giving Beethoven’s “Ninth Symphony” entire, and contented himself with liberal slices of Mozart’s “Twelfth Mass” and the more thumping oratorio numbers. Along with all this there were huge rations of Meyerbeer, Rossini, patriotic airs, the expressly composed pieces, the school children’s chorus, and a host of other novelties. But the two huge successes, aside from Gilmore himself, were the Anvil Chorus and his star soprano, Parepa-Rosa.

So difficult was the job of keeping 10,000 voices under control that he had his music stand equipped with a series of speaking tubes which connected him with his lieutenants scattered through the chorus sections. Beside the tubes was a row of telegraph keys which controlled the cannon battery outside. When the moment arrived for the anvils—this number, of course, was given at every performance— Gilmore would whistle up the tubes, gather his host together, and then let her go. At the climax he came down on the telegraph keys and in the bedlam of the cannon would bring the chorus to its close.

As for Parepa, she was so colossal that the reporters completely broke down. During the singing of the “Inflammatus” her voice, clear and strong, rose higher and higher until at last it could be heard, light and free, far above the huge chorus. At the end, the audience was dissolved in tears. It recovered when she reappeared to lead The Star Spangled Banner. Resplendent in white silk with red, white and blue buttons and with diamonds in her hair, she took the anthem to her giant bosom and summoned all her powers.

When it was all over it was found that the Jubilee would show a small profit and this profit, together with the takings at a testimonial concert, brought in nearly $40,000 for the bandmaster. It was his honest due and there was not a single catcall when the money was turned over to him, and he set out for Europe to recuperate from his labors.

The Lesser Jubilee

THE WORLD’S Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival was announced, to continue for three weeks, beginning on June 17, 1872, and running until July 4. A new monster auditorium was built, a new and vaster choir and orchestra were trained, the anvil rehearsals began again, and an organ larger even than the first was built.

Johann Strauss, at a reputed fee of $20,000, came to conduct the orchestra in The Blue Danube and all the other waltz marvels in his repertoire. The aged Franz Abt was also imported to take the 2000 musicians through his When the Swallows Homeward Fly. Arabella Goddard came and tried to play on an impossible piano supplied by one of the backers. A brigade of soloists was presented as “A Magnificent Bouquet of One Hundred and Fifty Artists,” along with Franz Bendell, the gymnastic German pianist. But the trump cards of this second festival were the visiting bands. Dan Godfrey brought that of the Grenadier Guards from London, all red and gold and bearskin; there was the Garde Republicaine Band (with the express permission of President Thiers) from Paris, and the Kaiser Franz Grenadier Regiment Band from Berlin. The Emperor also obliged with his Imperial Household Cornet Quartette. The procession wound up with the United States Marine Band, the Gilmore Band under its own leader, and an unfortunate organization known as the Irish National Band.

This last was not a success. Gilmore wanted the Irish Constabulary Band, but the British government thought Godfrey was enough and refused permission, whereupon an agent in Dublin hustled a band together and shipped it over, labeling it the Irish National. When it appeared at the festival its members had rehearsed but three weeks and had never played before in public. As might be supposed, their performances were not impressive. Worse, they fought one another continuously, and went to pieces completely after the festival was over.

But despite every bait, people simply refused to come. At a few of the performances—on Grant Day and at the visit of Horace Greeley—the house was fairly well filled, but at other times the spectacle was dire. The second day found 22,000 performers on the stage and but 7,000 in the audience. Sunday sacred concerts were attempted to help swell the takings, but so few came that they were abandoned precipitately.

The Balanced Band

GILMORE was forty-four years old when he got to New York in 1873 and entered upon the last period of his life. He had twenty years yet to go, and, if there were no thunder-crash climaxes any more, those last twenty years could scarcely be called anti-climax either. What was already the best band in America continued to grow even better. His passion for perfect performance led him to pay splendidly for talent and, as one of his associates said, “all his players, the elite of the musical profession and artists from all musical countries, were the greatest players on their respective instruments in the world.”

Herbert Clarke has told how laboriously Pat sought to achieve a perfectly balanced band and how he would argue with orchestral conductors that a band of 100 players, properly chosen, was superior to a symphony orchestra. Such a band Gilmore eventually assembled, and here it is:

2 Piccolos

2 Flutes

1 A-flat Piccolo Clarinet

3 E-flat Clarinets

14 1st B-flat Clarinets

10 2nd B-flat Clarinets

8 3rd B-flat Clarinets

2 Alto Clarinets

2 Bass Clarinets

4 Oboes

4 Bassoons

1 Contra Bassoon

1 E-flat Soprano Saxophone

2 B Soprano Saxophones

2 Baritone Saxophones

1 Contra Bass Saxophone

2 Alto Saxophones

1 E-flat Cornet

2 1st B-flat Cornets

2 2nd B Cornets

2 3rd B-flat Cornets

2 Flügel Horns

4 Trumpets

4 French Horns

2 Alto Horns

2 Tenor Horns

2 Euphoniums

1 Tenor Antoniophone

4 Trombones

5 Tubas

1 Bass Antoniophone

4 Drums, Cymbals, Timpani

2 Flutes

1 A-flat Piccolo Clarinet

3 E-flat Clarinets

14 1st B-flat Clarinets

10 2nd B-flat Clarinets

8 3rd B-flat Clarinets

2 Alto Clarinets

2 Bass Clarinets

4 Oboes

4 Bassoons

1 Contra Bassoon

1 E-flat Soprano Saxophone

2 B Soprano Saxophones

2 Baritone Saxophones

1 Contra Bass Saxophone

2 Alto Saxophones

1 E-flat Cornet

2 1st B-flat Cornets

2 2nd B Cornets

2 3rd B-flat Cornets

2 Flügel Horns

4 Trumpets

4 French Horns

2 Alto Horns

2 Tenor Horns

2 Euphoniums

1 Tenor Antoniophone

4 Trombones

5 Tubas

1 Bass Antoniophone

4 Drums, Cymbals, Timpani

This makes ninety-nine. The one hundredth man must have been Gilmore himself.

Chicago Has Its Fun

THE LAST of his big shows was given in Chicago in 1873, a series of huge concerts got up ostensibly to celebrate the recovery of the city from the great fire. These concerts were held in the concourse of the new passenger station of the Lake Shore Railroad and lasted for three days. A friend of Gilmore’s said that the “structure satisfied his idea of bigness for it was two blocks in length and accommodated 40,000 people.” He was able to fill it, and with an enlarged band of 300 and a chorus of 1000, he did the Anvil Chorus again. It was during these concerts that he told an acquaintance that “he wished he could have cannon, bells, and anvils with every piece he played, not only on account of the audience, but because he enjoyed them himself.”

He was one of the musical stars of the Centennial in 1876, sharing honors with Offenbach and Theodore Thomas. Not long before this Gilmore’s Gardens, housed in a huge structure between Madison and Fourth Avenues at Twenty-sixth Street, were opened, and here in the Summer of 1875 Gilmore made an extraordinary record. He gave 150 consecutive concerts to crowded houses. On October 29, the last night and his benefit, more than 10,000 persons jammed themselves inside the place to cheer him. The great moment was when Gilmore—his sideburns and chin-tuft were gone now, and a waxed moustache had taken their place—appeared with the three other great cornetists of the day, Arbuckle, Bent and Jules Levy, to play a quartette.

“The King is Dead!”

ONE AFTERNOON, playing at the St. Louis Exposition, his heart gave way. A few hours later, on September 24, 1892, all that was left of Patrick Sarsfield Gilmore lay in the Lyndall Hotel— his wife and daughter and two ambassadors of the Church beside him, but never a single cornet to serenade him on his way. Two days later Sousa’s Band, at Plainfield, New Jersey, gave its first concert and as a gesture of affection played Gilmore’s The Voice of a Departed Soul.

How the master would have relished that theatrical touch—but two days separating two eras!