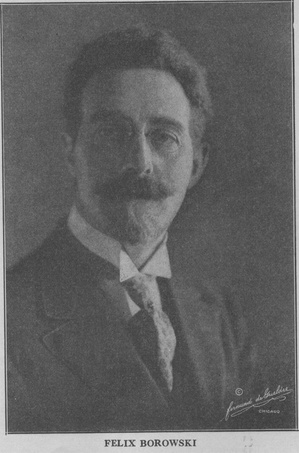

By the Eminent Composer, Teacher and Critic

FELIX BOROWSKI

Felix Borowski, born at Burton (Westmoreland), England, was educated first by private teachers in London, later at the Cologne Conservatorium, where he was a pupil of Jensen in composition, of Georg Japha in violin playing and in piano of Ernst Heuser.

Began his career by teaching in Aberdeen, Scotland, but in 1894 returned to London. His Russian Sonata for piano, published in 1896, attracted considerable attention and won strong commendation from Grieg, Rosenthal, Leschetizky, Rheinberger and others. The growing reputation of Borowski led, in 1897, to an offer from Dr. Ziegfeld, of Chicago, to come to America as head of the composition department of the Chicago Musical College. Borowski accepted this position and remained a member of the faculty of the institution until 1916, when he became its president upon the retirement of Dr. Ziegfeld. He resigned that position in July of this year and is now teaching privately in Chicago. In addition to his work as a composer and teacher, Borowski has been active in the literary field of music. He has been music critic for the “Chicago Evening Post” and the “Chicago Herald” and is now Chicago reviewer of music for the “Christian Science Monitor.” Since 1908 he has been the writer of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra program books.

Borowski’s compositions for orchestra include Elegie Symphonique, “Peintures ,” “Le Printemps Passionné,” “Youth,” “Ecce Homo,” Concerto for piano and orchestra, Allegro de Concert for organ and orchestra, and many others. He has written three sonatas and a suite for organ. In spite of his works in the large forms, it is probable that, as in the case of many other composers, Borowski owes his reputation largely to the little pieces which have come from his pen. His “Adoration” for violin has long been popular with performers on that instrument, and there are but few piano teachers who have not made use of his “Valsette” and other pieces in that genre. Our readers will find one of Mr. Borowski’s compositions in the music section of this issue.

IT IS ONE of the most remarkable features of musical composition that the great masters of it have been drawn, in the majority of instances, from the humbler ranks of society and that many of them have spent their existence’s romantically, if uncomfortably, in a condition of semi-starvation. The pre-eminence of the poor and the lowly in the field of musical creation has been so general that the average concert-goer would regard with surprise, and almost certainly with distrust, a symphony by a marquis or an overture by a millionaire. Yet there has been remarkable music written by composers who never have had to worry about their balances at the bank and who have practiced art for love and not for money.

IT IS ONE of the most remarkable features of musical composition that the great masters of it have been drawn, in the majority of instances, from the humbler ranks of society and that many of them have spent their existence’s romantically, if uncomfortably, in a condition of semi-starvation. The pre-eminence of the poor and the lowly in the field of musical creation has been so general that the average concert-goer would regard with surprise, and almost certainly with distrust, a symphony by a marquis or an overture by a millionaire. Yet there has been remarkable music written by composers who never have had to worry about their balances at the bank and who have practiced art for love and not for money.

In sketching an account of amateur composition it is not altogether easy to decide where to make a chronological beginning, or even to decide definitely what an amateur really is. It would be possible to start the list of upper-class composers with Nero, who certainly made music and who is said to have been inspired to a great burst of inspiration by the burning of Rome in A. D. 64 —a calamity he not only was believed to have originated, but which—if Suetonius and other historians are to be believed—he accompanied on the cithara. But it would scarcely be profitable to drag the ancients into this discussion. Neither will there be space in which to consider the artistic exploits of the kingly and princely troubadours of the XIIth and XIIIth centuries, although those representatives of musical composition produced work much fresher and more vital than that created by the monks, who were the official composers of the age.

It will be convenient to begin a survey of amateur composers by taking the sixteenth century as a starting point. Not least among the writers of music who sat in the high places was Henry VIII of England. That doughty monarch has been regarded with considerable disapproval because his inclination towards matrimony not only caused him to accumulate six wives but to chop off the heads of two of them. If there was a brutal and tyrannical side to Henry, there was also a tender and poetic side, and it was that which flowered into music. The king had been excellently trained in music and he practiced it assiduously, not only by composing but by playing on a variety of instruments and by singing. When one of the ambassadors sent by the Doge of Venice to Henry VIII, in 1515, reported on his mission, he described the king as “so gifted and adorned with mental accomplishments of every sort that we believe him to have few equals in the world. He speaks English, French and Latin, understands Italian well, plays almost every instrument and composes fairly.” And when, after the ambassadors had been banqueted at Greenwich, they were taken through the king’s palace, they were shown large numbers of virginals, recorders, harps and other instruments and the secretary of the Embassy played on one of them so well that it was remarked by one of Henry’s courtiers that he was certain that the king would like to hear him, for his (the courtier’s) master “practiced day and night.”

Although the Doge’s ambassador declared that Henry VIII composed “fairly,” it is certain that he failed to do the fullest justice to that monarch’s accomplishments as a creator. Henry’s music is still occasionally heard even to-day and his song Pastime With Good Company shows no little ability from the standpoint of XIVth century technic, and no little imagination and melodic charm. The British Museum contains in its library eighteen compositions with words by Henry and fifteen without. These include two masses and an anthem which, entitled O Lord, The Maker Of All Things, was regarded by the historian Burney as being so advanced in style that he was disinclined to credit its composition to the king.

The Virgin Queen

HENRY VIII’S daughter, Queen Elizabeth, of glorious memory, also was an amateur in music, although there is no record of her accomplishments as a composer. Some verses published in 1573 thus referred to her:

“The Queen, the glory of our age and isle,

With royal favor bids this science smile;

Nor hears she only others’ labored lays,

But, artist-like, herself both sings and plays.”

The royal amateurs of England did not, however, have things altogether their own way. João IV King of Portugal, a contemporary of Henry VIII, rivalled the latter in his love for music as well as in his ability to interpret and to write it. His compositions included a number of motets and other forms of church music and João was active as a musical litterateur, as, for instance, in his “Defense of Modern Music,” in which he contested the opinion of Bishop Cyrillo Franco, that music should be banished from the services of the church. Nor should there be forgotten the magnificent musical library which the king collected and which unluckily was totally destroyed in the great earthquake which visited Lisbon, in 1755.

The XVIIth century saw the rise of dramatic music in Italy and the development of instrumental art. The majority of those who cultivated it were men—and women, too—who belonged to the upper classes and who made music for their pleasure. Interest in the Nuove Musiche, or the New Music, had been manifested in the previous century, and one of the leaders in the little band of enthusiasts who, in their attempt to revive ancient Greek drama, brought the opera into existence, was Giovanni Bardi, Count of Vernio, at whose palace in Florence there met the men Galilei, Caccini, Peri, Corsi, Rinuccini who made musical history. Some of Count Bardi’s associates—Peri and Caccini, for instance—were professional musicians, but others were amateurs, and of the latter Jacopo Corsi was probably the most influential. It was in his palace in Florence that “Dafne”—generally regarded as the first opera—was performed in 1597. Peri, the composer of that work, stated in his preface to the opera that it had been written at the instigation of Corsi and of the poet, Rinuccini, in order to “test the effect of the particular kind of melody used by the ancient Greeks and Romans throughout their dramas.”

Corsi was not merely a nobleman who gave his moral support to the Nuove Musiche; he took a practical part in its development, and when in 1600 Peri produced his “Euridice”—apparently a portion of that opera had been Composed by Caccini—the work was not only produced at the Palazzo Corsi, but the master of that establishment presided at the harpsichord, with three of his noble friends respectively performing on the chitarrone, the viol da gamba and the theorbo, or large lute. It should be added that Corsi was a composer as well as a harpsichordist, and there is reason to believe that he had a hand in the writing of Dafne. Count Bardi also wrote music, and a five-part madrigal by him is still in existence. That the Florentine amateurs were of great importance in the development of music is certain, and it is interesting to recall that Giulio Caccini, who was one of the most notable of the early XVIIth century masters, declared that he had learned more from them than from thirty years of training in the schools of counterpoint.

The Italian dilettanti were not all of the male sex. At the time Count Bardi and his colleagues were developing the new music, Vittoria Aleotti, a native of Argenta, was continuing the old, and her Ghirlanda dei Madrigali a 4 Voci appeared in the print in Venice in 1593. Nor should there be forgotten Francesca Baglioncella nor Orsina Vizzani, the latter in particular having been a popular composer of madrigals in the early part of the XVIIth century. But even in the domain of early opera the men were not allowed to occupy the field alone. There was Barbara Strozzi, whose Diporti d’Euterpe was staged at Venice in 1659.

Frederick the Great

MUSICAL DILETTANTISM flourished exceedingly in the XVIII century. Not least interesting among its representatives was Frederick the Great, King of Prussia. At the period in which he lived—1712-1786—the fashionable instrument for a gentleman was the flute. Frederick was a passionate devotee of it, a curious instrument for the delectation of a military tyrant, but he not only bent his energies assiduously to the mastery of the flute, but composed much music for it. For many years the royal manuscripts lay in the archives at Potsdam and other places, but in 1835 Frederick’s successor, Frederick William III, had a search made for them, and 120 compositions—principally for flute—were discovered and, edited by Spitta, were eventually published in 1889. Frederick the Great had begun to learn the flute at the age of sixteen, but as his father believed music to be an effeminate amusement, his lessons had to be taken secretly. Even after he was twenty Frederick was constrained to play duets with his valet, for parental authority forbade any consorting with musicians. The heyday of the royal amateur’s music came with his accession to the throne of Prussia in 1740. Quantz, one of the most celebrated flautists of his day, was engaged as kammermusicus and court composer at a salary of two thousand thalers, in addition to a bonus of 25 ducats for each of his compositions for flute solo and 100 ducats for every flute which he made for the king. He composed 299 concertos for Frederick, and died while the three hundredth was still unfinished. The king, however, completed the work.

Frederick was not the only musical amateur in his family. His sister, Princess Anna Amalia, was a composer even more ambitious than he. She studied with Johann Philippe Kirnberger, who became director of music in the princess’s establishment, and she was a contrapuntist of unquestionable ability. Anna Amalia composed a setting of Ramler’s “The Death of Jesus” and a large number of smaller works. Another Anna Amalia of the XVIII century who occupied herself with composition was Duchess of Saxe-Weimar, who made a musical setting of Goethe’s “Erwin and Elmira,” and who composed chamber music. There was still a third royal Amalia—Maria Friederike Amalia, Princess of Saxony, whose efforts largely were centered in opera. Some fourteen examples of dramatic composition came from her pen, and most of them were received from the Saxon public with the respect which was due to one who was a Personage as well as a composer. One must not leave the highly-born ladies of Saxony without a reference to Maria Antonia Walpurga, electress of Saxony and daughter of the Emperor Charles VII. She was born in 1724 at Munich and studied with Porpora and Hasse. Her opera Il Trionfo della Fedelta was performed in 1753 before Frederick the Great, who condescended to add to it a number or two from his own kingly pen. It is to be hoped that the court criticism was leavened with discrimination, for although Il Trionfo della Fedelta was produced as the work in text and music of the illustrious Maria Antonia, the text was partly the creation of the great Metastasio, the most celebrated librettist of his age, and the music had partly been composed by Hasse. Which suggests Brahms’ caustic remark to a colleague who, having made some derisive comments upon a composition for orchestra by one of the minor German rulers, was warned by the master not to speak disrespectfully of the music of princes, “for,” said Brahms, “one can never tell who may have written it!”

Marie Antoinette

THERE WERE noble amateur composers among the women of France as well as among those of Germany. The hapless Marie Antoinette was the composer of songs and her setting of Florian’s C’est mon Ami is full of charm. The Comtesse Stéphanie Félicité was a contemporary of that queen and was famous for her compositions for the harp as well as for her virtuosity on that instrument. None now remember Mme. Brillon de Jouy, but her playing on the clavecin, as well as her compositions for it, attracted considerable attention in the elegant world of Paris, and Dr. Burney, who heard her in the French capital, was moved to devote a paragraph to Mme. de Jouy’s accomplishments in his book, “The Present State of Music in France and Italy,” which he published in 1770. Sometimes the French dilettanti were precocious, as, for example, Mlle. Guenin, who, born at Amiens in 1791, produced an opera—“Daphnis et Amanthée”—when she was only sixteen years of age and won a great success with it. Precocious, too, was an earlier composer, Mlle. Jacquet de la Guerre. At the beginning of the 18th century she caused something like a sensation with her clavecin playing as well as with her sonatas and other works for the instrument, and she was not more than fifteen when her fame was noised among the salons. In the same field of art and at the same time the Marquise de la Mizangere occupied the attention of connoisseurs.

That the cultivation of art was continually spreading was made evident by the universal respect for it shown in the 19th century and by the ever-increasing number of men and women who practiced music as amateurs. It would seem, perhaps, far-fetched to include Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy and Giacomo Meyerbeer among the dilettanti; yet neither of those illustrious composers had to earn their bread and butter by their gifts, although both added considerably to their fortunes by means of them. Mendelssohn was the son of a banker, and his mother as well as his father was wealthy. The elder Mendelssohn hesitated to allow his son Felix to take up music as a career, but once it became evident that the boy was supremely gifted—and that circumstance was disclosed very early in his existence—he not only was given the teaching and every artistic advantage that a professional musician should have, but the commercial experience of Abraham Mendelssohn was brought to bear upon his son’s preparation for a life of art. Thus the practical side of a musical career was ever with Mendelssohn, as it was not with so many other great composers who—like Mozart, Schubert and others—had to create music as part of their means of subsistence. When, in 1840, Mendelssohn offered the English rights of his D Minor Trio to J. J. Ewer and Co., London, for 10 guineas ($52.50) he made no objection to an arrangement of the slow movement and scherzo for flute “as” he wrote “I am almost sure that these two movements, even separately, will be played by amateurs with pleasure in that shape.” This practical appreciation of the financial aspect of his genius accompanied Mendelssohn throughout his life. If he was technically an “amateur,” the composer of “Elijah” was thoroughly professional both in the skill with which he wrote his inspirations and in the cleverness with which he marketed them after they were set down.

Meyerbeer, like Mendelssohn, had a banker for his father. Rich as was the composer through the paternal branch of his family, he was independently wealthy by reason of a legacy left him by a rich relative whose name—Meyer—he took along with the bequest. Wagner’s jibe at Meyerbeer—“a Jew banker to whom it occurred to compose operas”—was altogether undeserved. Whatever may be the defects of Robert le Diable, Les Huguenots, Le Prophète or Meyerbeer’s other operas, there can be no doubt that the success which came to them was the result of hard work and unceasing energy on the part of their creator. Meyerbeer, like Mendelssohn, was an amateur, inasmuch as he composed for the love of art and not because he had to make a living, but his attitude toward his work was not less earnest than the attitude of Wagner to his.

During the XIXth century Germany held the supremacy of music, and it was natural that the cultivation of it spread to every class. The rulers of the various principalities and kingdoms which Bismarck united in the German Empire in 1871 were practically at one in their devotion to art. Most of them supported orchestras or opera houses, or both, and not a few emulated Frederick the Great in composition. Ernst II, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, was an opera composer in the ‘fifties. Possibly a duke, even if he is also a dilettante, has less difficulty in obtaining productions for his operas than he would have if he were merely of plebeian stock. Ernst II brought forward dramatic compositions in Brussels, Paris, Vienna, Hamburg and Coburg, and one of them—“Santa Chiara”—was even heard successively in Gotha, Paris and London. They were listened to with respect in Germany, but opera-goers in other lands were cold when they were not derisive. Even New York was made acquainted with one of His Royal Highness’ productions, for the Duke’s Diana von Solange was staged at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1890. Mr. Henry Edward Krehbiel, who wrote illuminatively upon the history of dramatic music in New York, professed himself unable to account for the production of Diana von Solange. “The most cogent argument in explanation of its production,” he wrote in “Chapters of Opera,” “was based on familiar stories of the lavishness of the Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in the distribution of orders, especially among musicians. No anecdote was more popular for the rest of the season in the corridors than that which told of how a concert party driving away from the ducal palace discovered that the Chamberlain had handed over one more decoration than the artists who had entertained the duke. ‘Never mind,’ quoth the Chamberlain; ‘give it to the coachman.’”

The duke’s brother, husband of Queen Victoria of England, also dabbled in music, for he not only composed “Invocation to Harmony” for solo voices and chorus, as well as a number of songs, but he played the organ. Mendelssohn visited the English royal family at Buckingham Palace, London, in 1842, and described the accomplishments of the Prince Consort in a letter to Mme. Mendelssohn, his mother: “I begged that the Prince would first play me something,” he wrote, “so that, as I said, I might boast about it in Germany; and he played a chorale by heart, with the pedals, so charmingly and clearly and correctly that it would have done credit to any professional; and the Queen, having finished her work, came and sat by him and listened, and looked pleased.” Nor was the musical influence of the Prince Consort lost upon his children. The Duke of Edinburgh, the second of his and Queen Victoria’s sons, performed on the violin—rather badly, it must be said—and frequently played in the first violins of the Royal Amateur Orchestral Society in London during the ’80s and ’90s. The Queen’s grandson, William II, of Germany, also essayed composition, and his “Sang an Aegir,” published some twenty-five years ago, brought down the imperial displeasure upon the heads of a number of critics in Germany, who ventured honest opinions.

Of the lesser German princes who have attempted the more ambitious exercises in musical composition perhaps the most notable was Heinrich XXIV, Prince of Reuss-Köstritz, who wrote no fewer than six symphonies, a mass for solo voices and orchestra and a considerable amount of chamber music. Not a few members of the German nobility practiced musical composition with more or less success; some, indeed—as in the case of Heinrich Picot de Peccaduc, Freiherr von Herzongenberg or Hans Bronsart von Schellendorf—with so much success that, as in the case of Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer, they we’re regarded as professional musicians. The same applied also to certain of the nobility of Italy and France. Of the noble amateur in the former country a typical example is Baron Alberto Franchetti, son of Baron Raimondo Franchetti and Baroness Luisa Rothschild. A pupil of Draeseke in Dresden, Franchetti became imbued more with the German than with the Italian style, but he was a true Latin in the enthusiasm with which he devoted himself to the operatic stage. Franchetti’s first opera was Asrael, which was given in Italy in 1888. Christopher Columbus, Fior d’Alpe, II Signor di Pourceaugnac, Germania, La Figlia di Jorio and other operas followed, and some of them—Asrael, Germania and Christopher Columbus—have been heard in America.

Similar to the Italian Franchetti is the French Baron Frédéric d’Erlanger. This musician was born in Paris of a German father and an American mother, but he is now living in England. Like Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer and Franchetti, he comes of a family of bankers, which circumstance explains the fact that d’Erlanger writes music because he wants to and not because he has to. At least one of Baron d’Erlanger’s operas has been heard in this country, for in 1913 the Chicago Opera Company produced his Noël. The baron’s Tess, founded upon Thomas Hardy’s novel, Tess of the Durbervilles, was brought out at Naples in 1906 and later staged at Covent Garden, London. In addition to two other operas, Jehan de Saintré and Inez Mendo, d’Erlanger has composed a violin concerto (which Fritz Kreisler performed in London), a string quartet, a piano quintet and a suite for orchestra. One must not leave the noble amateur composers of France without a mention of Mme. Marie Félicie Clémence de Reiset, Vicomtesse de Grandval. That lady produced seven operas in her native country, as well as a Mass and Stabat Mater and some miscellaneous pieces for orchestra. A concerto for oboe and orchestra of her composition was performed in Chicago in 1908.

(In the next issue Mr. Borowski will discuss famous Russian Musical Amateurs.)