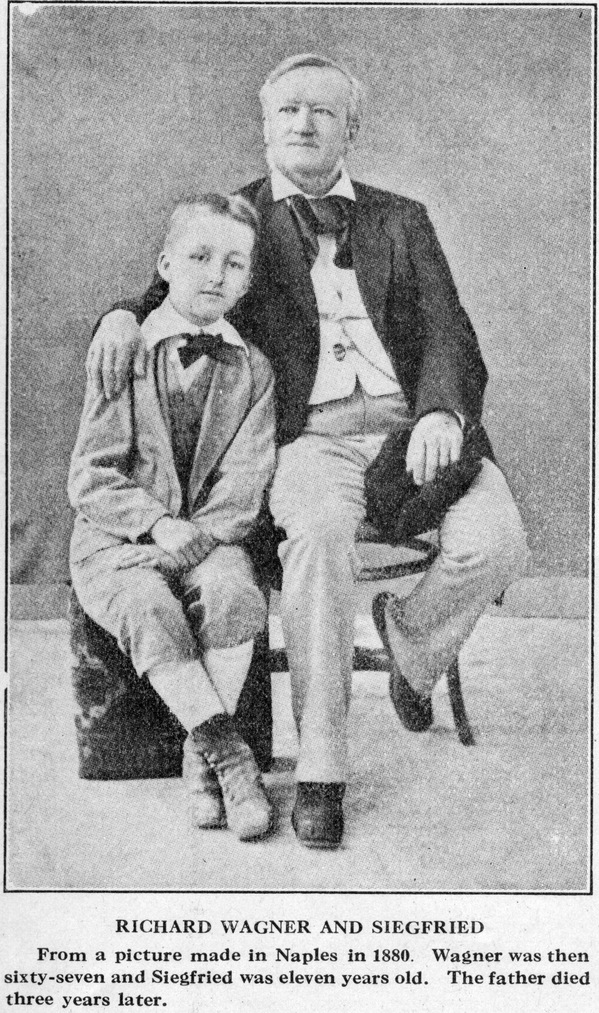

Siegfried Wagner was born June 6th, 1869, at Triebschen. His parents wished him to become an architect, and he studied this subject at a Polytechnic School. Later he studied music under Kniese and Humperdinck. He became a concert conductor in 1893 and later became conductor at the Bayreuth Festivals (1896). He has written eleven operas, of which the best known is “Der Bärenhäuter” (“The Bearskins’). Suffering the greatest handicap imaginable by being the son of a musician of transcendent genius, his works were immediately compared

Siegfried Wagner was born June 6th, 1869, at Triebschen. His parents wished him to become an architect, and he studied this subject at a Polytechnic School. Later he studied music under Kniese and Humperdinck. He became a concert conductor in 1893 and later became conductor at the Bayreuth Festivals (1896). He has written eleven operas, of which the best known is “Der Bärenhäuter” (“The Bearskins’). Suffering the greatest handicap imaginable by being the son of a musician of transcendent genius, his works were immediately compared

with those of his father. As the grandson of Liszt and the son of Wagner he has inherited traits of genius that many in his native land believe will some day entitle him to recognition as a great composer, which critics who insist upon comparing his works with those of his father refuse to give to him at the present. It is his ambition to have his work judged individually and not as the son of a great master. As a conductor Siegfried Wagner has met with wide success. He conducts without score and with his left hand. He is now touring America in the interests of Bayreuth.

The underlying trait of my father’s character was a lofty artistic earnestness. Along with this, however, there poured forth an illuminating humor and a sunny happiness which, notwithstanding the difficult life situations and the disappointments, rarely resolved into satire or irony.

How highly he prized that gift of God, a wholesome laugh, is revealed in his advice given in a letter to his old friend, Uhlig:

“Rely absolutely upon humor. Cultivate thereby, more and more definitely thy excellent gifts. Do not write another serious word but keep on laughing and laughing. That is the only way to get along in life and prove useful to others.”

That Wagner himself was in possession of this Godlike gift and intentionally cultivated it is manifested very beautifully and strikingly in his Beckmesser and Mime.

The humor of my father was in common with that of all genius. He, for instance, had a very intimate appreciation of the humor of Schiller. As an example of this, he wrote to Mathilde Wesendonck:

“Schiller has a distinctive humor which possesses a geniality and wholesomeness which I have never been able to discover in the works of Goethe.”

About Shakespeare he writes:

“These wonderful witty laughs in Shakespeare. This divine scorn. It is really the highest point a human being can attain.”

In his remarks about Beethoven he says:

“We cannot fail to see a basic relationship between Shakespeare and Beethoven. Further, it may be said that in the quickness of grasp, in the peculiarity of the humor, we recognize in the expression of the humor

of Shakespeare’s characters an inexplicable spontaneity, that in an exactly similar manner gives the types of motives of Beethoven the highest ideality; that is, they are the unavoidable melodic forms demanded by the mood.”

Later Wagner remarks:

“Never has the art of the world produced any happier or livelier works than Beethoven’s symphonies in A major and in F major, and others of the intimate creations of the master written in the time of his complete deafness.”

In connection with the A Major Symphony, which was loved by my father above everything, may be given the two following anecdotes of a lighter character:

In the year 1873 Wagner attended a rehearsal of the A Major Symphony which was to be given under the baton of Zumpe. When it came near the end of the third movement, Wagner rushed to the conductor’s desk, grasped the baton from Zumpe, and besought the orchestra to play the movement over again. Little by little Wagner increased the tempo. The orchestra, gradually led by the master into a dancing and fluctuating whirlpool, gladly obeyed his flying baton. The movement closed with a wild whirlpool—the fastest possible tempo. With the last note of the orchestra, Wagner threw the baton on the floor, whirled around joyfully upon the little conductor’s stand and then leaped back at least two yards. Turning aroung (sic) instantly, he rushed back to the dumfounded musicians, exclaiming, “Do it like that. Mach’s nach!”

When Wagner Danced a Beethoven Scherzo

At the last meeting of Wagner with Liszt, in Venice, the latter—my grandfather—played the Beethoven A Major Symphony. My mother, the Princess Hatzfeld, and some others listened. We children sat in the adjoining room. Suddenly, with the beginning of the Scherzo, my father entered and, unnoticed by Liszt and the audience, commenced to dance in the most elegant and graceful manner. He appeared like a youth of twenty years. We children had difficulty in refraining from showing our joy by loud outbursts of laughter. One thing is certain, Beethoven could never have wished to have his Scherzo danced more beautifully.

The admiration of Liszt for my father was so deep and his comprehension of his character, which was so very often misrepresented, so great that little jokes like this were accepted in a friendly spirit.

Once, after my grandfather had played a religious composition, I do not recollect whether it was from his “Christus” or not, my father said:

“Your God makes a great deal of noise.” (Dein lieber Gott aber viel Spektakle.”)

On All Fours

Most of the time when Liszt played Bach and Beethoven, Wagner listened with prayerful silence. Suddenly he would rise and, going to Liszt, would pet him like a child. This he did quite often; and Liszt used to look at him with a stern glare in his eyes. Once, after Liszt had played, Wagner crept over to him on all fours, saying:

“Franz, to thee, one must creep on all fours.”

In the presence of his family and friends, and particularly with artists, happiness and joy always affected his mood. Very often upon the arrival of an unexpected but very welcome guest, upon any joyous occasion, or from mere exuberance of good spirits, he would stand upon his head.

Gustav Adolf Kietz, who was working on a bust of Wagner, relates the following which occurred after a pianoforte rehearsal at Bayreuth, in the year 1875, when Wagner was sixty-two years old:

“Once when I was working upon Wagner’s bust and looked over to him to get the proper expression, I was frightened to see his face turned into a horrible grimace, his mouth open at least an inch, his eyes distorted, the veritable countenance of a Leipzig street rowdy.”

My sisters received lessons in French daily from my mother, in one of the upper rooms of our house. A spiral stairway led directly to this room. Every now and then my father would appear upon these stairs, unseen by my mother, and make faces and all kinds of fun for my delighted sisters.

At the Bayreuth rehearsals Wagner took the liveliest interest. If all went well, that is if it went as he wanted it, Wagner manifested his thanks in the kindest and most humorous manner. At one of the “Parsifal” rehearsals he addressed himself to the interpreter of Amfortas, who had performed the rôle as he wished it done. “To you I have a ten-mark piece. You can accept it in good grace. When Schnorr sang Tristan in Munich, I gave him only three marks.”

After the rehearsals of “Das Rheingold,” Karl Hill, who played Alberich, received a bottle of champagne, and the Rhine Daughters, because of their courage in trying out the somewhat hazardous apparatus employed to make them appear as though swimming, each received a beautiful bouquet.

During the time of the rehearsal of the “Nibelungen Ring” in Bayreuth the dog tax of the municipality was considerably increased. The celebrated violinist, Wilhelmj, at that time was our concert-meister. He heard of this and, being a great lover of animals, feared that many owners would find the tax so high that they would let it slip by and permit their animals to be destroyed. To save the poor animals from this fate, he bought about a dozen of the dogs and confined them in a wooden shack next to the theater. With the first pianissimo of the orchestra the whole bunch began to bark and bay and howl in an unbearable manner. Of course, they had to be liberated at once. At the close of Wilhelmj’s “Rheingold” solo, Wagner slowly walked down the stage and said to Wilhelmj in the orchestra, “Very beautiful. Very beautiful. You shall have a new dog.”

Wagner delighted in sitting down with his artists after rehearsals and engaging in jovial chats. At such times his irrepressible humor was evident. Upon one occasion, when a group of his artists were remaining rather late in a restaurant they were amazed to see Wagner appear in the gallery, with a bear skin over his shoulders, a helmet on his head and a spear in his hand, singing the famous lines of the Night Watchman, “Hört ihr Lent und Lasst euch sagen.” (“Hear me people and let me say to you.”) One who was present reported, “The effect was a riot of laughter and amusement.”

Mottl and the ballet master, Fricke, describe in similar manner a garden fest in honor of Mme. Materna, at Wahnfried. This was followed by a satirical play - really a burlesque at the Hotel “Zur Sonne.” It was a veritable vaudeville in which Lilli Lehmann danced a two-step (pas de deux) with Fricke, while Mottl played the piano and Hermann Levi accompanied him on the bass drum. Wagner remarked at the end, with extravagant explosions of good humor, “We artists are an irrepressible lot. Such an evening as this is incomprehensible to others and is therefore falsely criticised. Therefore it is best to live to ourselves.”

Wagner often discussed himself and his works, in a thoroughly humorous fashion. Thus at an after-dinner speech in Dresden, where he had been Kapellmeister in his youth, he fell into one of his humorous moods. He gave a review of his youth in Dresden, when he was an unknown musician, when he had presented himself at the opera house with a very thick manuscript of “Rienzi.” “It was my poor ‘Rienzi,’ which still every now and then is presented here like a plucked chicken.”

(Translator’s Note:—Wagner here refers to the innumerable cuts made in the usual performance of his very lengthy original manuscript of “Rienzi.”)

When “Lohengrin” was being revived in Vienna Wagner sat upon the conductor’s stand making remarks to Elsa and Ortrud about their duet at the end of the second act, permitting the orchestra to continue to play the remainder by themselves. Wagner was amazed at the beautiful warm tone of the Viennese violinists, who of course united to make the ensemble very effective under such conditions. He turned to them and said:

“You have played it much more beautifully than I have composed it.”

When he came to the same passage on the evening of the performance he laid down his baton and let the orchestra continue alone, he laughing heartily to himself over his joke, and at the same time indicating his great confidence in their orchestra, to the Viennese public. This was greeted with such stormy applause that Wagner was forced to rise and acknowledge it with a bow. Turning to one of the musicians nearby, he remarked: “It appears that the public is even better pleased when I do not conduct.”

Then he laughed heartily and gave the signal to continue the performance.

In his memoirs he comments with keen humor upon his first tragedy, “The plot was really quite remarkable; forty-two of the characters died during the course of the piece, so that it was necessary to bring them back as, ghosts in the last act—otherwise I could not have had a last act.”

Many anecdotes of this first tragedy have been recounted by Wagner’s sisters. In one occult moment, one of the living personages approached one of the ghosts who shouted in caution, “Back! Touch thou not my countenance, because my nose will crumble in dust as soon as one touches it.”

A visiting friend once asked the youthful dramatist how far he had proceeded with his drama, and the reply was: “Thus far, I have killed all the characters.”

Once with the celebration of his birthday, which fell upon the twenty-second of May, he made the following amusing verse:

“Ja, ja, es war im Mai

Da war ich auch dabei,

Man zog mich bei den Ohren roth,

Drum bin ich musikalisch geworden”.

Freely translated:

Yes I was born in May

And I was there they say;

Some one took me by the ear

And made me musical I hear.

On another birthday he wrote:

Im wunderschönen Monat Mai

Kroch Richard Wagner aus dem Ei,

Es wünschen viele, die Ihn lieben,

Er wäre besser drin geblieben.

Freely translated:

Ah ‘twas the lovely month of May

That hatched the Wagner egg one day;

They wish, who loved their Wagner best,

The egg had perished in the nest.

Visitors with whom he was unacquainted were not as a rule welcome. Once when he returned from a walk he said:

“Alas, one cannot even walk out in peace. Some one asked me on the street to-day if I was really Wagner.

“‘No,’ I replied, ‘I am not Wagner.’”

Another curious person met him once, just as he was leaving the apartment house in which he lived.

“Does Richard Wagner live here?” asked the sightseer.

“Certainly,” replied Wagner; “Two flights up, go right up,” and Wagner went upon his way.

When he purchased the lot on which to build Wahnfried an amusing episode occurred. All points of the sale were settled but one. On the middle of the lot there lay a huge pile of manure which Wagner wanted and which the former owner was loath to give up. Finally it was settled by Wagner sitting at the piano and playing for the seller the Blue Danube Waltz of Straus.

An instance of his sarcasm and irony was his brilliant description of the French dramatist Scribe.

“One encounters Scribe, dressed in a most elegant silk dressing gown, sipping a cup of chocolate. He requires this refreshment because he has just left his workdesk after two hours’ hard ride in his romantic wonderland where he has laughed at the works of all the great authors. Do not think, however, that he is resting while he is drinking his chocolate. Look you, in every corner of his gorgeous room one may see, upon chairs, settees divans, all the leading authors and composers of Paris. With each one of these worthies Scribe is engaged upon some different piece of business. With one he plans a new play, with another a new opera or a new comedy or a new vaudeville, with this one he invents a brand new intrigue, with another he discusses the effects of a new opera, with another he has planned in a second a double marriage. At the same time he is busy writing a great number of beautifully styled letters, or perchance he has just paid five hundred francs for a dog. During all this he has gathered material for his next production, laughingly studied the characters, welcomed and dismissed various strangers, ordered a frame for himself and made a new drama which no one had hitherto suspected.”

Before closing this little sketch of the humor of my father I would like to add by way of an “Epitaph” which he wrote with pessimism but unconstrained sarcasm, shortly before the turn in his life when his fortunes rose:

Hier liegt Wagner, der nichts geworden,

Nicht einmal Ritter vom lumpigsten Orden,

Nicht einen Hund hinter’n Ofen entlockt er

Universitäten nicht ‘mal’ nen Doktor.

Literal Translation;

Here lies Wagner, who is nothing,

He has not ever received a knighthood of the meanest kind;

He has not been able to coax a cur from behind a stove,

Nor a degree from any University.