Basic Principles in Pianoforte Playing

SECTION IV

Secured Exclusively for THE ETUDE by Interview with the Famous Virtuoso Pianist

JOSEF LHEVINNE

This Series Began in the “Etude” for October. Each Section May be Read Independently

In the last section of this series the all important matter of securing a fine tone was considered. In this the reader will remember that, in addition to the ability to conceive a beautiful tone mentally, attention was called to the fact that richness and singing quality of the tone depends very largely (1) upon the amount of key surface covered with the well-cushioned part of the finger and (2) upon the natural “spring” which accompanies the loose wrist. While the following remarks may be read independently of the foregoing sections, the student will do well to re-read them to fix certain fundamental principles in the mind.

In the matter of delicacy, the student may well give earnest attention to anything which will contribute this exquisite quality to his playing when the composition demands it. To be able to play with the delicious lightness and beauty of Cluny lace should be the ambition of all students. A beautiful lace shawl is the best comparison I know to what I mean by delicacy in playing. There is lightness, fineness, regularity of design, but without weakness or uncertainty.

The Technical Side

The technical side of the problem is not so difficult to explain. In the first place the upper arm and the forearm must feel so light that the player has the impression that they are floating in the air. The mental attitude here is very important. Delicacy is inconceivable with a heavy arm. The least suggestion of tightening or cramping of the muscles is literally fatal to delicacy. One may say “relax” the arm; but if the arm is completely relaxed it will do nothing but flop limply at the side. On the other hand, it can be held in position over the keys with entire absence of nervous tension or stiffening, with the “floating in the air” feeling that makes for the first principle of delicacy.

Before proceeding further it might be well to note that the player can actually think moods and conditions into his arm and fingers. His mental attitude means a great deal in the quality of his playing. Just as the voice immediately reflects in its quality the emotions of great joy, pain, sorrow, scorn, meanness and horror, so do the fingers and the arm in somewhat similar fashion respond to these emotions and represent them in playing for those who have mastered the technic of playing so that they are not concerned with details which should become automatic. Anyone heard Rubinstein play will realize how the emotions can be conveyed to the keyboard in an altogether marvelous manner. No audience is immune to this appeal. The non-musical auditors, in fact, come more for this sensation than for any understanding of pure music. They know instantly when it is present and go away gratified and rewarded. They do not understand the musical niceties; but they do comprehend the communication of human sensations and emotions when sincerely portrayed by the pianist who feels that he has something more to do in his art than merely to play the notes.

Floating in the Air

To return to the matter of delicacy. If the student has mastered the principle of the “arm floating in air” (and it is something to be gained more by the right mental attitude than by any specific practice), the next step is to realize that delicacy does not consist merely of lightness. There are thousands of students who can play with some degree of lightness but who miss or slight so many notes in the course of a composition that their playing is really irritating, even to the non-musical listener. Delicacy must not be secured at the sacrifice of completeness. For this reason, even in the most delicate passages, every key struck, black or white, must go all the way down to key bottom. This is most important. Don’t have your lovely lace shawl filled with holes or worn places.

The third principle in the practical matter of securing delicacy is to play with the fingers on the surface of the keys. That is when you raise your fingers you do not take them perceptibly away from the surfaces. This simple matter insures the player against to forceful a stroke and makes the playing more uniform. It is

difficult to do, especially with impatient students; but the matter of delicacy should be studied at a slow tempo so that the student can analyze his finger and arm conditions. He should repeatedly interrogate himself:—

Important Questions

Is my arm floating?

Am I striking each note to “key bottom”?

Am I keeping my fingers on the surface of the keys?

In playing for delicacy the key is struck with the finger tip rather than with the fleshy ball as when producing the full round singing tone. I also notice that when I am trying to secure a “floating arm” condition, my elbow extends very slightly from the side of my body[.]

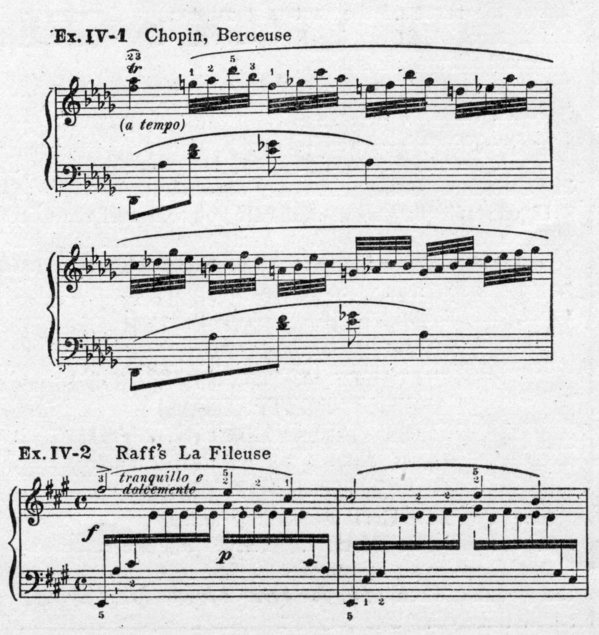

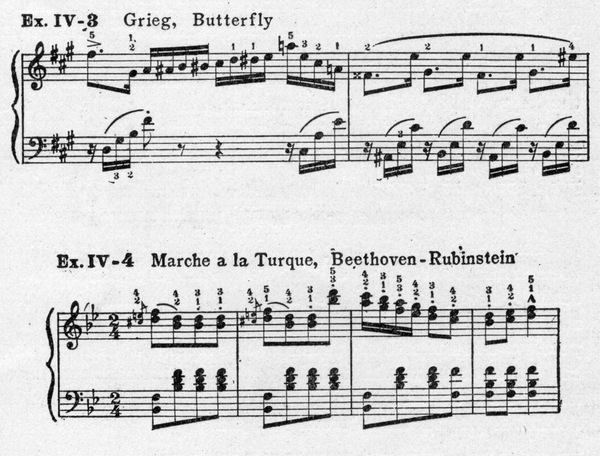

Practice for delicacy may be accomplished through thousands of pieces and exercises. The following passages are examples of particularly good material for use in this connection.

Power in Playing and What It Means

Every teacher encounters pupils who are physically very strong and who can easily produce noise at the keyboard. On the other hand there are pupils who are not particularly strong, but who play with very great power. What is the reason? Of course strength, real physical strength, is required to play many of the great masterpieces demanding a powerful tone; but there is a way of administering this strength to the piano so that the player economizes his force. I know of one famous pianist who has always inclined to the immovable torso or body in playing. He sits like a rock on the piano chair, producing all his effects by means of strokes or blows to the keyboard. Much of the great playing I have heard has been produced by altogether different means. Consider, for instance, the picture of Rubinstein presented herewith. The artist has caught something here which the photographer has missed in most of the portraits of Rubinstein at the keyboard. This was probably because Rubinstein may have posed when he knew he was before the camera. But, this sketch is Rubinstein as I knew him. Notice that instead of sitting bolt upright, as the pictures in most instruction books would have the pupils do, he is inclined decidedly toward the keyboard. In all his forte passages he employed the weight of his body and shoulders. This was most noticeable; and the student should remember that when playing a concerto, Rubinstein could be heard over the entire orchestra playing fortissimo. The piano seemed to peal out gloriously as the King of the entire orchestra; but there was never any suggestion of noise, no disagreeable pounding.

Natural Shock Absorbers

Why no noise? Because Rubinstein’s wrists were always free from stiffness in such passages and he took advantage of the natural shock absorber at the wrist which we all possess. He employed in principle the touch we have discussed in previous sections of this series and his playing assumed a power and a grandeur I have never heard since his time, but to which I always aspire as my life Ideal in my public performances. He did not pound down upon the keyboard but communicated his natural arm and shoulder weight to it.

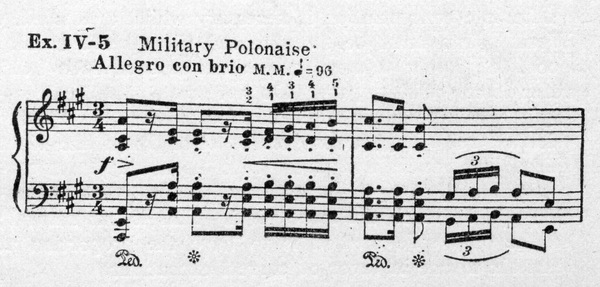

There is a vast difference between the ordinary amateur hammering on the keyboard for force and the more artistic means of drawing the tone from the piano by weight or pressure properly controlled or administered. Take the first movement of the Chopin Military Polonaise, for instance.

Play this first with stiff wrists and forearms, and notice how bangy and disagreeable it sounds. Now play it with the wrists loose, employing the fleshy parts of the fingers and feeling that the weight and power are communicated to the keyboard from the shoulder. This beautiful composition is often ruined by banging, whereas it may be delivered with a lovely tone and rich singing quality. The same is true of the B-flat Minor Scherzo, which is another of the musical anvils of the typical conservatory. If Chopin could hear how this is murdered, he would turn in his grave. Instead of being given with nobility and grandeur, its opening passages are banged out with sledge hammer blows that are altogether unforgivable.

There is an acoustical principle involved in striking the keys. If the blow is a sudden, hard, brutal one, the vibrations of the wires seem to be far less pervading than when the hammers are operated so that the wires are “rung” as a bell.

Accuracy in Playing

Because in his later years Rubinstein was now and then inclined to miss a note or so in the course of a recital, indulgent students have assumed that since the message of the master composer is so much more important than the little matters of technical details, they can improve upon Rubinstein and leave out a great many more notes. Rubinstein’s playing in his youth was doubtless immaculate from the standpoint of accuracy. In his last years the bigness of his musical conceptions and the greatness of his soul were such that he burst all bonds to give his great message to the public. We can forgive Rubinstein anything; but in these days of keenest competition the student must look upon inaccuracies as unpardonable. The subject of accuracy is so important that we shall require more space for its discussion and it will be taken up in the next Section along with “The Basis of Fine Staccato.”

This notable series by Mr. Lhévinne will be continued in the next issue of The ETUDE Music Magazine. We are delighted to inform our readers that we have secured a number of articles of this character from the greatest authorities. Each article sheds new light upon the subject of better pianoforte playing. The ETUDE has for years aspired to be the bridge between the student and the teacher and the great concert artists. Every article has a thoroughly practical bearing.