NEW AND IMPORTANT SERIES OF LESSON-ARTICLES-SECTION III

Basic Principles in Pianoforte Playing

Secured Exclusively for The Etude by Interview with the Distinguished Virtuoso Pianist

JOSEF LHÉVINNE

This Series Began in the “Etude” for October. Each Installment May be Read Independently.

The Attention of Etude Readers is Called to the Editorial on “Beautiful Tone” Page 814

Mr. Lhévinne’s ideas upon technic, tone and interpretation are not only distinctive in their force and simplicity, but also are expressed with terms which make them readily remembered. For years, many of the great pianists of the world have applauded his remarkable technical ability and his audiences are fascinated by the delicacy of his tone. THE ETUDE feels that it is rendering a real service to the profession and to the art by presenting this exceptional series of articles. The succeeding articles in the series will be filled with practical ideas.

The Secret of a Beautiful Tone

“It will be remembered that in the previous section of this series a promise was made that we would next attempt to determine the “secret” of a beautiful tone. In this connection it must be recollected that considerable attention was given to the matter of individuality. In the first place, every piano student who aspires to acquire a beautiful tone must have a mental concept of what a beautiful tone is. Some people are born with a sense of the beautiful in sound. They do not need to be told. It is like the finely balanced sense of color possessed by some, in contrast to those who are color blind. If you have this sense of tonal beauty you are lucky. If you do not have it, do not despair; because, by hard work and experience in listening to pianists who do possess a beautiful tone, you may develop it. I have known innumerable students with a very disagreeable tone, who have in time developed an attractive one by persistent effort. However, if you are tonally deaf to lovely sound qualities there is very little hope for you.

“On the other hand, there are those who have a natural tonal sense but who do not have the technical qualifications for producing good tone at the piano; and it is to those that my remarks are now directed. The adjustment of the hand and arm to conditions that produce good tone is half of the battle. That is, the student must get clearly in mind what contributes to good tone production on the keyboard. In work with my masters, in personal investigations of technical principles, and through hearing intimately most of the great pianists, from Rubinstein to the present, certain basic facts seem to be associated with those who have good tone in contrast to those who do not.

Cushions of Flesh

“In the previous section we have spoken of the part of the finger that comes in contact with the keys. If that part is well covered with cushions of flesh, the tone is likely to be far better than if it were hard and bony. Therefore, the main principle at the first is to see that the key is touched with as resilient a portion of the finger as possible, if a lovely, ringing, singing tone is desired instead of the hard, metallic one. What part of the finger tip is this? Certainly not the part immediately behind the finger nail. There the tone produced is still bony and unresponsive. Just a little farther back in the first joint of the finger you will notice that the cushion of flesh is apparently more elastic, less resisting, more springy. Strike the key with this portion of the finger, not on the finger tips as some of the older European methods suggested. To accomplish this, I would call your attention to the illustration in Section II, in which it is distinctly stated that the finger moves as a whole and at one joint only—the joint connecting the finger with the body of the hand. If the fingers descend upon the keys in this fashion you will notice that they do not strike on but just a little behind the tips. In other words, the key is touched with as large a surface on the first joint of the finger as is feasible.

It is almost an axiom to say that the smaller the surface of the first joint of the finger touching the key, the harder and blunter the tone; the larger the surface, the more ringing and singing the tone. Naturally if you find a passage requiring a very brilliant, brittle tone you employ a small striking surface, using only the tips of the fingers. This is just one of the elements of good piano tone; but it should be mastered by all progressive piano students. Indeed, this in itself will improve your tone immensely, even though you may not employ some of the other principles which we shall discuss later. Before dismissing the subject, let the student think for a moment of the luscious quality of tone which often accompanies melodic passages in which the thumb is used a great deal. This is due in no small measure to the large, springy cushion of flesh on the thumb, in contrast with the much smaller cushion employed with the fingers, by the student who has been trained to strike with the very tip of the finger.

The Part the Wrist Plays in a Good Tone

“Very few students realize the part the wrist plays in the production of a good tone. If they were compelled to ride at a high rate of speed, over a rough road, in an automobile without springs or shock absorbers, they would go through a very terrible experience, They would be jarred and bumped almost to death. Yet that is what many students actually do in their piano playing. If the cushions of flesh on the ends of the fingers are the pneumatic tires in piano playing, the wrist is the spring or the shock absorber. For this reason it is next to impossible to produce a good singing tone with a stiff wrist. The wrist must always be flexible. The more spring the less bump; and it is bumps that make for bad tone on the piano.

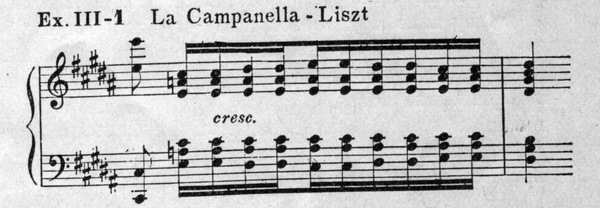

“Of course, if you are playing a passage like the following from the Liszt Campanella, where the greatest possible brilliancy is demanded, a stiff wrist and pointed fingers are not only permissible, but absolutely necessary.

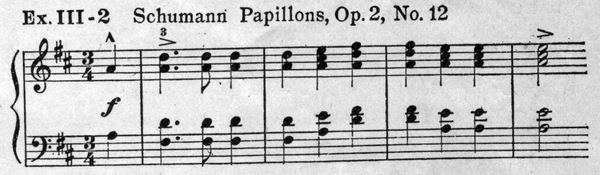

“Or a passage like the following from the Schumann Papillons, which should be an imitation of brass instruments, must be played with pointed fingers and stiff wrists.

“Or a passage like the following from the Schumann Papillons, which should be an imitation of brass instruments, must be played with pointed fingers and stiff wrists.

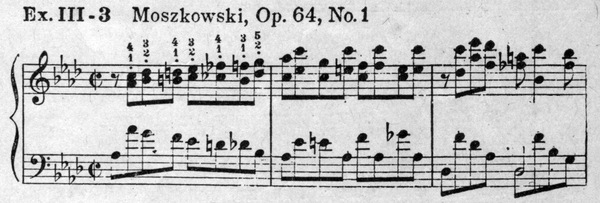

“The same is true of the following lovely passage from Moszowski (sic) Etude In Double Notes, Opus 64, only with a lighter touch.

“The same is true of the following lovely passage from Moszowski (sic) Etude In Double Notes, Opus 64, only with a lighter touch.

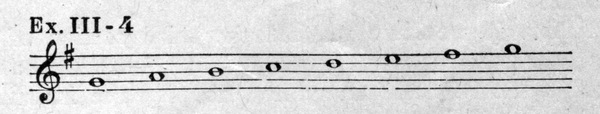

“The cultivation of a singing touch should be a part of the daily work of every student who has passed the first few grades of elementary study, if indeed it may not be introduced earlier with students of more mature intelligence. All sorts of exercises will be devised by the skillful teacher. One of the simplest is to take the simple scale like this.

“The cultivation of a singing touch should be a part of the daily work of every student who has passed the first few grades of elementary study, if indeed it may not be introduced earlier with students of more mature intelligence. All sorts of exercises will be devised by the skillful teacher. One of the simplest is to take the simple scale like this.

“Poise the hand about two inches above the keys. Hold the hand in normal position as you would upon the piano keyboard (not with the fingers drooping down toward the keys). Now let the hand fall a little with the first joint of the second finger, the wrist still held very flexible so that the weight of the descending hand and arm carries the key down to key bottom, quite without any sensation of a blow. It is the blow or the bump, which is ruinous to good tone. The piano is not a typewriter to be thumped upon so that a sharp, clear type impression will be made. Rather imagine that you are actually playing upon the wires, ringing them with soft felt-covered hammers and not with hard metal bars.

“As the hand descends for this swinging touch, the finger is curved normally; it is not held straight. As the finger touches the key-surface, it feels as though it were grasping the key not striking or hitting it. There is a vast difference of sensation here. Always feel as though you had hold of the key, not that you are merely delivering a blow to it. Do not think of the ivory surface of the keyboard as you would of a table. That idea is entirely wrong. Those who play the piano as though they were strumming on a table will never get the innate principle of a good tone.

“Again when the hand descends, as large a surface of the finger tip as feasible engages the key; and the wrist is so loose that it normally sinks below the level of the keyboard. Observe your hand sensations very carefully. The tone is produced in the downward swing of the hand. If it were possible to take one of the exaggeratedly slow moving pictures of this touch, there would be no spot, no place, no movement where the movement seemed to stop on the way down. If there were such a place it would produce a bump. The tone seems to ring out beautiful and clear. The key is touched “on the wing,” as it were, in the downward passage. All this concerns only the first note of the melody or a phrase, the other notes, if the melody to be played legato must be taken with the fingers quite near the keys raising or dropping the wrist according to the design of the melody.

“The student who values a good tone will have the patience to practice all his scale/in both hands, one finger at a time, until this principle becomes automatic, until it is just as natural as free and easy walking. He will find that his playing becomes more graceful, more pleasurable, more satisfying to his sense of tonal beauty and to his hearers. But he has to listen!

“When he attempts a powerful forte passage later in his musical life, he will discover that he can make the piano ring with the greatest possible volume, without making it sound “bangy”. The reason why a number of people say that they do not care for piano playing is that so many so-called performers upon the instrument treat it as though it were an anvil and go on hammering out musical horse shoes.

“In Section 1 of this series some of the Etude readers may have been a little out of patience with the extent of my remarks about rests. If rests are important, the method of stopping the sound of the note is quite as important as the method of sounding it. The most superficial examination of the inside of the keyboard reveals that the sound is stopped by the felt damper coming up against the keys. In brilliant compositions, such, for instance, as the Mendelssohn Scherzo in E Minor, in a passage like this the sound must stop quickly and abruptly as in all full staccato passages.

“But in melodic passages it is very offensive to have a ‘sound bump’ at the end of the tone. Therefore, at the end of the tones in melodic passages the student reverses the process by which he produces the tone. The wrist must be gradually raised and go high until the finger will leave the key, like an aeroplane leaves the ground; and, of course, the key itself ascends gradually and the damper comes up to the wire without the ‘bumping off’ sound. Many, many students strike the keys right but do not seem to have mastered the very simple, but very vital principle of releasing them so that there is no jerkiness. Details? Aha’—these are the details upon which those who aspire to be masters work their hardest.

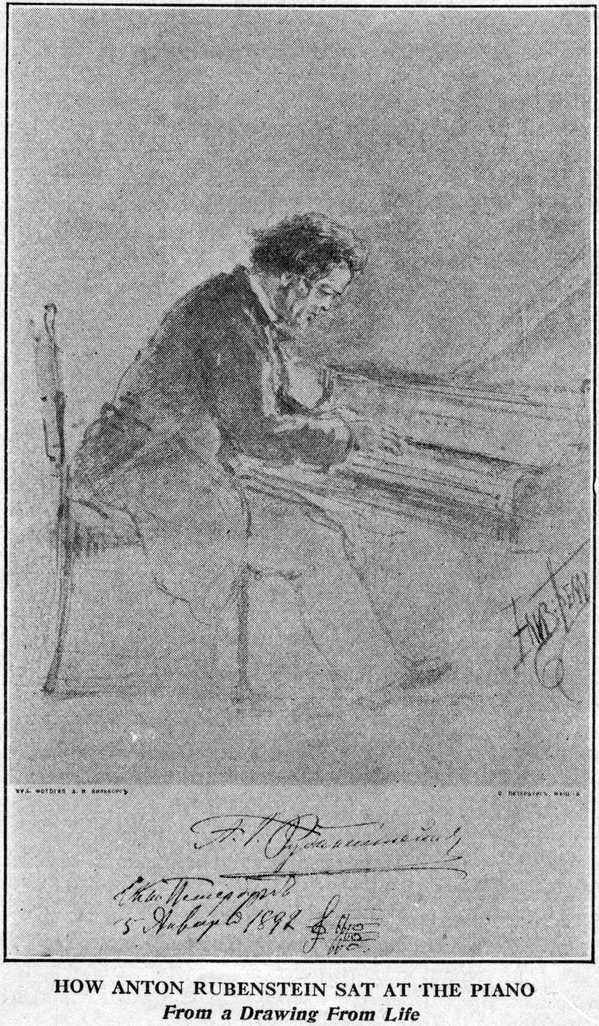

“Although we have reached the third section of our discussion of this fascinating subject—which has so much to do in determining how to play the instrument so that it will be really musical in contrast to the street piano we have been able as yet to cover only a few of the main points. In the next section we shall take up the matter of how to acquire great delicacy of touch and its antithesis, great power. This will be illustrated by a rare Russian portrait of Anton Rubinstein in a position at the instrument in which we shall attempt to show how that famous ‘lion of the keyboard’ produced some of his powerful effects.”