Conducted by Arthur de Guichard

Learning to Play Sharps.

Q. I find that I am able to read much easier in flat keys than in sharps. The scale and arpeggios of D flat seem to me to be quite easy and familiar, while the key of its enharmonic C# is horribly difficult and almost unplayable by me. Is there any method I can adopt to overcome this difficulty?—Eva S., Philadelphia, Pa.

A. It is, probably, only certain # keys that you find difficult, such as F# and C#, 6 sharps and seven sharps. Most likely you find the same difficulty with the flats, when you come to G-flat and C-flat, and you much prefer the key of B (five sharps) to that of C-flat (7 flats). The cause is not very far to seek. It is evident that you avoided practicing the extreme keys of 6 and 7 sharps and 6 and 7 flats, when you studied your technical work.

The most urgent thing you have to do is to practice, with the music before your eyes constantly, these extreme keys in scales, chords and arpeggios, supplementing them with finger exercises à la Plaidy. This must be persevered with until you have completely mastered the “look” of the music and its technical execution.

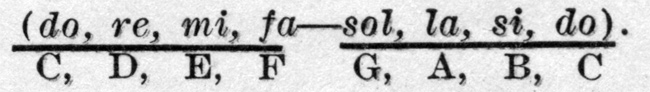

But there is another help quite as important, not only for these but for all other keys and their reading. Learn to read your music in the light of the movable DO, making each keynote a DO with its scale sequence (DO, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si, do), remembering always that the half-steps (semitones) are between mi-fa and si-do. Instead, therefore, of playing mechanically, your mind will be helping you all the time. Work diligently along these lines for scales, chords, arpeggios and finger exercises and the pianists’ bête noire of “sharps” will speedily abandon you.

Games Stiffen Fingers.

Q. I am much devoted to outdoor sports and to all athletic exercises, but find that my fingers get extremely stiff after my games and gymnastic exercises, so that it takes me quite a long time to get into my stride in piano playing. I am considered a fair performer on the instrument, but do not seem able to do much after a little exercise with the clubs, or a game at golf, baseball, or tennis. What do you advise?—Herbert W. W., New York City.

A. Adopt that which you care for the most; but you cannot go in for manual exercise and games of the nature you describe, and play the piano well. If it is your ambition to become a professional pianist or a good amateur, you must renounce every form of finger, hand, wrist and arm work which will stiffen or interfere with the freedom of those parts. Avoid everything which militates against their suppleness. There are plenty of fine exercises for the development of body and health, which do not entail hand cramping.

Daily Scales.

Q. I am told that I have a very good touch. That being so, do you think I need to practice scales every day?—A. M., Boston. Mass.

A. Most decidedly; not only all your scales for finger dexterity, but your slow scales for evenness of touch: quality and intensity. Practice them every day until you are eighty—or more. In this way your playing will always be young, elastic and adequate.

Trills.

Q. In playing trills I find that there seem to be two customs: (a) to begin the trill on the note over which the sign is written; (b) to begin the trill on the note immediately above the one which has the sign. Which is the correct method? If both are right, how am I to know which one to observe?—Ivan S.

A. The correct way to begin a trill is by playing the diatonic note (that is, the note of the scale) immediately above the written note; a chromatic note is played for the trill only when the # or flat is indicated. The only occasions when the trill may begin on the written note are: when that note is a very short one, therefore requiring to be made more prominent and with a very short trill—in fact, a species of mordent; and when the trill is developed out of the written note, which has been struck and is being held.

In all compositions prior to the year 1828 the trill should begin on the upper note (unless otherwise written). In that year Hummel wrote a pianoforte method, in which he endeavored to alter the accepted practice of playing the trill, by making it begin on the written note. Many composers since his time have adopted his method, whence the confusion. In any event, it will be absolutely correct for you to begin the trill with the upper note in all compositions dating before 1828.

Small Hands.

Q. I have a very small hand and play extensions with, great difficulty. Would you recommend the use of any mechanical device to increase its spread?—Teacher, Plymouth. N. H.

A. Certainly not. Many a promising young player has become permanently disabled from such malpractice.

Why Study Bach?

Q. Is it absolutely necessary for me to study Bach—his Inventions and Preludes and Fugues? My teacher is a great stickler for Bach, and almost worries the life out of me with these Inventions.—Celia, Boulder Colo.

A. There is music and music. It all depends upon what you consider music. If the height of your ambition is to play “rag” and “jazz” you may omit the study of Bach, although even for them you would find his music very useful. You find Bach dry and tiresome because, most probably, you approach him the wrong way. But if you will take the trouble to analyze his melodies, or subjects, or themes, and then to memorize them, you will be astonished to learn how interesting they are and how wonderfully they are treated. No matter what your ultimate ambition may be, if you wish to become a competent pianist you must make Bach your best friend.

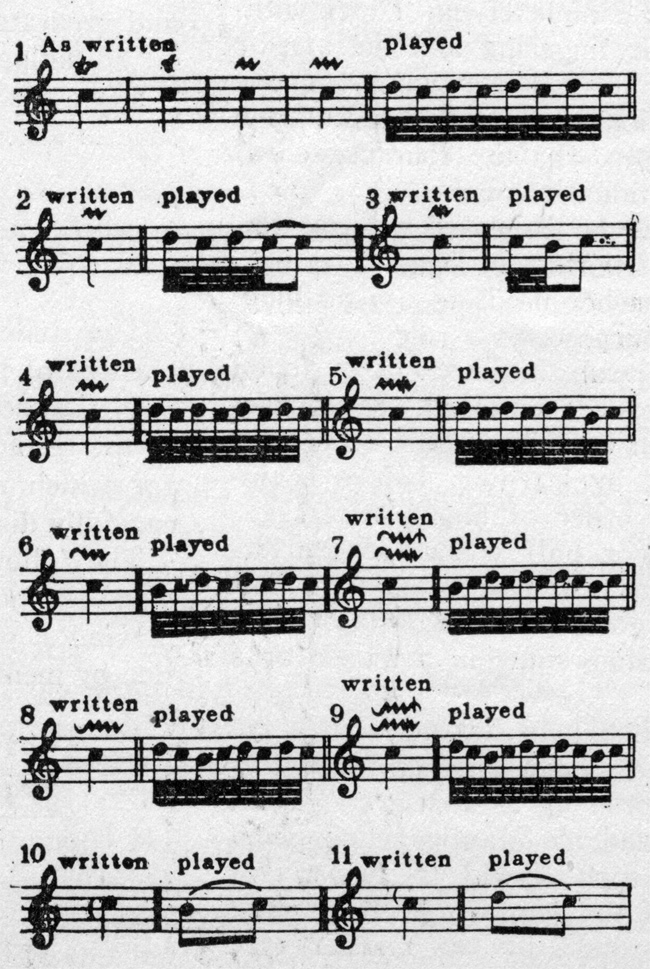

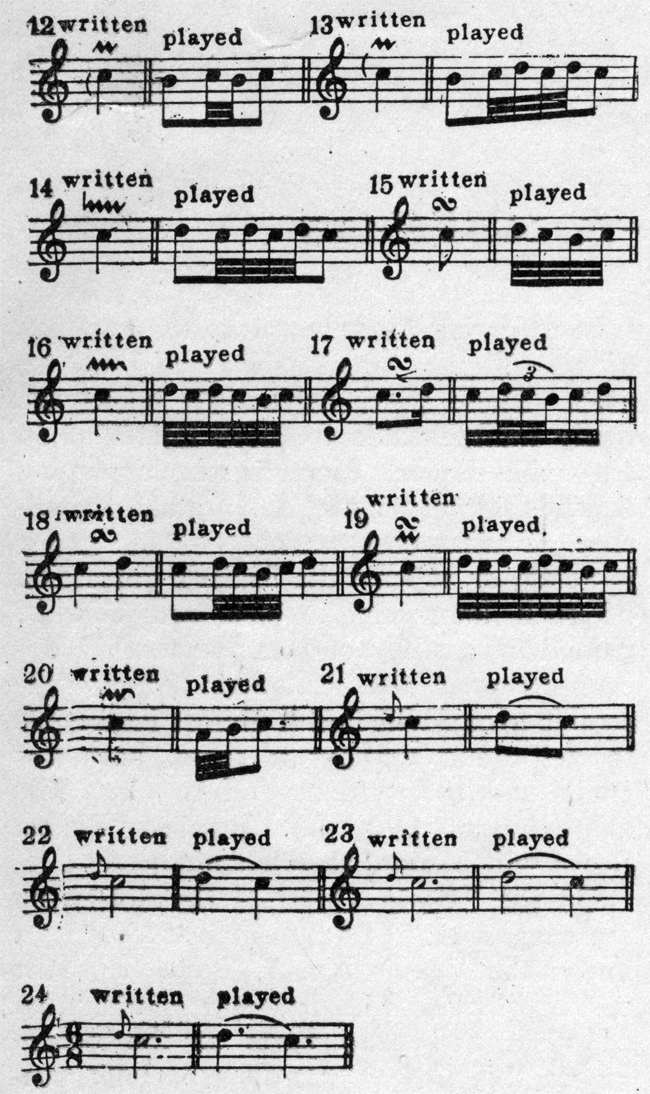

Bach’s Musical Ornaments

Q. I would be deeply obliged to you if you would indicate how to play the ornaments which abound in the works of Johann Sebastien Bach. There are so many different interpretations of their signs that I would really like to have you supply an authoritative decision on the subject.—H. W. G., Philadelphia, Pa.

A. There can be no doubt whatever about the exactitude of the first fifteen interpretations in the following list, for the very good reason that they were supplied and signed by Bach himself in a book for the Clavier, which he prepared for his son Friedemann. It is worthy of notice that the trill in Bach’s works, as well as in those by other composers, before and of his time, always begins on the note above the principal note—any other rendering would be erroneous. At the same time it should be observed that these ornaments were invented for the clavecin, or clavichord, an instrument that was entirely destitute of the rich, round tones of the modern pianoforte. On this instrument, therefore, they should be used sparingly, and never exaggerated. Because it must not be forgotten that these ornaments were invented in order to fill up and compensate for the otherwise thin, hard, dry tone of the clavichord.—L. M. P., California.

Largo and Adagio.

Largo and Adagio.

Q. Which is the slower movement “Largo” or “Adagio?” Has the second term any diminutive form?—G. A. S., Providence, R. I.

A. Largo, the same as Grave, is the slowest movement. Adagio is a quicker movement, although writers of to-day interpret it in a much slower sense than the original Italian, which is about equivalent to what we understand by Andante. Its diminutive is Adagietto.

Why Not Opera in English?

Q. If I am not asking too much, could you explain to me (and I think it would interest my fellow-readers also) how it is that in the two countries in which English is the language of the people, England and the United States of America, all opera of a high order is sung in a foreign language and English is ignored? Who started the custom, or fashion? Have there been no good composers of opera in English?—A. H., New York City.

A. It is impossible to give in this place an adequate reply to the question; need of space for other questions forbids. Very briefly, therefore—in a sketchy outline, as it were—a few evident reasons may be stated for the unfortunate lack of English “grand” opera—and when we say “English,” we really mean national; national as regards words. In France, Italy and Germany opera is sung in the language of the people, the plebs. Opera in these countries would not flourish otherwise. The demands of the national language require the interpretative talent of a national musician. England had its national opera for a short period, during the life-time of her greatest musician, Henry Purcell, who, before his death in 1695, had contributed some thirty-nine compositions to the English stage. He was succeeded by the great composer, George Friedrich Händel, born in 1685, about four weeks before the still greater Johann Sebastian Bach. Händel re-introduced Italian grand opera into England and, both as composer and impresario, made it the chief musical function of fashionable society. Ever since his day and up to the present time opera in a foreign language has been the vogue in Great Britain—and this country has followed suit! All kinds of reasons might be advanced for this deplorable state of things, the chief one being that there are no American or English composers talented enough to write grand opera! Nevertheless, let there be a steady demand for national opera and, by degrees, national composers and national singers will arise to supply the demand. The “running after other gods” is but so much snobbery. The proof? The majority of those who rule the operatic situation in London, New York and Chicago do not understand the languages sung, but have to rely upon most inadequate translations.

Since Purcell’s time there have been good composers of English opera, chief among them being: Balfe, Wallace, Benedict and Macfarren. Arthur Sullivan, of Piriafore fame, contributed largely to the stage works which come under the denomination of ballad operas, very much in the style of The Beggar’s Opera (1728), entirely English. As for native singers, England possesses many, who are quite capable to interpret roles in grand opera, and the United States has a still greater number of excellent artists, both in voice and interpretation. Let there be a real, urgent demand by the people for National Opera and both composers and artists will be found to fill the demand. But it must be opera for the people, not a society function.

Pythagoras and Aristotle.

Q. Were the Greek philosophers Pythagoras and Aristotle really musicians, as we understand the term? Which was the greater? Do any of their compositions exist to which one might refer? Were there any other Greek writers or composers of music in ancient times—authentic, not fabulous?— Geo. s., Lonsdale, R. I.

A. Pythagoras, born at Samos about 582 B. C., celebrated Greek philosopher and mathematician. He believed and taught his disciples the doctrine of metempsychosis, or tranmsmigration (sic) of souls. Nothing positive (that may be proved) is known about him. He is supposed to have invented the multiplication table and to have established the mathematical relations of sound vibrations as emitted by strings. By many his existence is regarded as problematical. In any event no writings of his have come down to us, because, like Socrates, he taught by word of mouth. About Aristotle we have documentary evidence of his existence and of his great learning. He was born about 384 B. C. in Macedonia. He was teacher and friend of Alexander the Great, and was one of the greatest intellects that ever existed. His known writings contain very little about music, but the information found therein is of the highest importance concerning the Greek art of music. Other ancient Greeks who wrote, more or less, about music were: Aristoxenus, of Tarentum, pupil of Aristotle, known in antiquity as “the musician,” who instead of founding his musical theories upon mathematics, based them upon the experience of his musical ear; Aristides Quintilian, author of a three volume treatise on music; Plutarch also wrote a short but valuable treatise on music, the authenticity of which is doubtful. Many other names could be cited, but à quoi bon? They teach but little that is of practical use.

Chief Points in Singing.

Q. What do you consider to be the most important desiderata in the art of singing? or rather I should say the science or TECHNIC of Singing? I wish to know what are the chief points to which I should direct my studies in order to use my voice properly, as I am told it is a good one.—George W., Columbia.

A. The three most important essentials in the technic or science of singing are: 1. Perfect breath control at and by the diaphragm. 2. Complete muscular flexibility and freedom; that is, no voluntary tension or muscular effort anywhere, save at diaphragm. 3. The tongue must not be allowed to obstruct the free flow of tone; when used in articulating consonants it must immediately resume its normal position, namely, inert, on the floor of the mouth, loosely touching the lower teeth all around.

Diction in Singing.

Q. Does diction, in singing, belong to the technic or to the art of singing? Is it as important a study as tone production and placement? Which is better for a singer to possess: a perfectly even, equal voice of beautiful quality, or a voice much less beautiful, but whose diction, style and interpretation are excellent?—Lucy A., Providence, R. I.

A. Diction, in singing, has a technic all its own. It is an art in itself, indissolubly connected with interpretation and without which no singer is even adequately prepared, no matter how good the voice. Beautify your voice as much as possible, but do not forget that a singer’s greatest assets are diction and interpretation.

Syllables or Letters Oldest?

Q. Which is the older method of naming the notes? Do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, si or A, B, C, D, E, F, G?—W. B., Orono, Maine.

A. The alphabetical system in its primitive form dates back to about 700 B. C., whereas the syllables do, re, etc., date only from the time of Guido d’Arezo, at the beginning of the eleventh century, namely: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la. The syllable ut is still employed by the French for the note C. The Italians, however, discontinued the ut for the syllable do about the end of the seventeenth century. The syllable si, for the seventh degree, was introduced about the beginning of the seventeenth century—by whom history recordeth not. It should be remarked that the A, B, C, D, E, F, G of the ancients correspond to the notes la, si, do, re, mi, fa, sol. One great point of similarity between the Greek and our modern system is well worth our notice. They both consist of two perfect tetrachords of two and one-half tones, separated from each other by one whole tone; but, whereas the Greek tetrachord begins with one-half tone, ascending, followed by two whole-tones (mi, fa, sol, la—si, do, re, mi), our tetrachords begin with the two whole-tones followed by the one-half

It is also worthy of notice that our system is designed chiefly for harmony, constructed upwards; the scale being tetrachordal, consisting of two whole-tones and one half-tone, then a link of one whole-tone joining the first to a similar tetrachord, all ascending. The Greek system, designed entirely for melody, constructed downwards, also tetrachordal, consisting of the same series of tones and half-tones, but all descending.