To be Tried Before THE ETUDE Readers as a Grand Jury Should the Operas of Richard Wagner be Debarred in America Now?

The Managements of the Grand Opera Houses in America have Announced that all German Operas shall be debarred during the War.

The Etude has carefully refrained from entering into any discussion bearing upon the propriety of discontinuing the services of German musical artists in America during the present war.

As an American publication, educational in its aim and contents, The Etude pursues a consistent policy in all such matters.

There is a difference, however, between the music of German masters of the past and the musicians of the present who may or may not be helping Germany through their earnings in America.

When Bach and Handel were born, America was still, to a very large extent, the land of the Redman. Shall Americans deprive themselves of the music of those masters who could hardly dream of any conflict between unexplored America and their native land?

Moreover, the music of the great German masters of the past is admittedly the result of phases of civilization far different from those which inspire the Germany of to-day.

If we were at war with England would we repudiate Shakespeare, Milton, Scott, Dickens, Thackeray or Tennyson?

Is it a part of our patriotism to renounce all the beautiful music that has come from Germany in the past in order to combat the enemy of the present?

The Etude is not deciding these questions. It merely propounds them. We would like to have the great number of our readers render a decision in

THE TRIAL OF RICHARD WAGNER

The Etude does not hold a brief for or against Richard Wagner. Richard Wagner was unquestionably a German. He was born at Leipzig, May 22nd, 1813. His parents were German.

It has frequently been contended that he was a Hebrew,—that his maternal ancestral name was Adler. Mr. Oscar Sonneck, formerly Librarian of Congress, has gone to great lengths to show that Wagner was not a Hebrew.

Wagner’s education was typically German,—Day School, Gymnasium and ultimately the Leipzig University.

Practically all of Wagner’s youth was spent in the country of his birth, Saxony. Saxony was long the arch-enemy of Prussia in many wars. Saxony did not join with Prussia in the German Empire until Wagner was fifty-seven years of age.

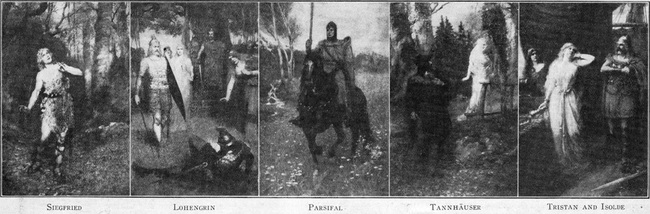

Six of Wagner’s Great Music Dramas (Tannhäuser, Meistersinger, Rheingold, Walküre, Siegfried and Gotterdämmerung) are monuments of German life, tradition and mythology. His other operas (Die Feen, Flying Dutchman, Lohengrin, Tristan and Isolde and Parsifal) are laid in other fields.

In England, some extremists have gone so far as to say that the works of Wagner are responsible for the present world unrest,—that they have been the ferment which have been the greatest German psychological influence upon the present generation.

At the same time, Wagner concerts have been given in London during the war with great success.

Again, this son of a Police Clerk was at one time so wholly democratic that if he had had his own way Germany would have been a republic as long ago as 1840.

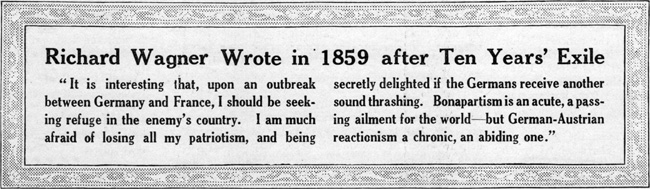

The suppression of the May Revolution in Germany (1849) caused the exile of many of Germany’s bravest thinkers. Among them were Carl Schurz and Franz Sigel, who became Major Generals in the United States Volunteer Army in the Civil War. Wagner at the same time was forced into exile and penury (for eleven years) because of his emphatic attitude against what we now know as Prussianism.

It is true that in his later years he was forced to seek the patronage of a Bavarian King, but at the same time he was essentially a Democrat with infinite vision.

Mr. Henry T. Finck in his two-volume Life of Richard Wagner says: “On June 14, 1848, Richard Wagner printed in a newspaper extra a fiery address containing some remarkably bold statements. In it Wagner demanded, besides general suffrage, nothing less than the complete abolishment of the aristocracy as well as the standing army, and the proclamation of Saxony as a Republic by the king himself, who was to remain its president.

Mr. Henry T. Finck in his two-volume Life of Richard Wagner says: “On June 14, 1848, Richard Wagner printed in a newspaper extra a fiery address containing some remarkably bold statements. In it Wagner demanded, besides general suffrage, nothing less than the complete abolishment of the aristocracy as well as the standing army, and the proclamation of Saxony as a Republic by the king himself, who was to remain its president.

One of Wagner’s biographers, R. Pohl, who was called by Wagner “The oldest Wagnerite” states that Wagner did not stand musket in hand on the barricades, when the Prussian troops came to suppress the revolution, but that he had charge of the “musical direction” of the revolution,—the sounding of alarm bells and the giving of signals. Pohl also states that Wagner organized the convoys coming from outside and gave them encouragement to fight.

However serious Wagner’s offence against the German aristocracy may have been, it was sufficient to cause him to seek flight disguised as a coachman and deprived him of the support of his fellow-citizens for many years.

Allowing that Wagner Operas could be given in the English language in America, without rendering personal assistance to dangerous alien enemies, should they be debarred from our stage at the present time?

This is the question we wish our readers to decide. Is it necessary or advisable for the safety of our Government and the satisfaction of the feelings of the public to forego for the time what one well known American critic has called “The grandest and most original musical dramatic compositions of all times?”

In a forthcoming issue of The Etude we will print the best brief for and the best brief against this issue. For each brief we shall give

A PRIZE OF TEN DOLLARS

CONDITIONS

All briefs must be received before May 15th, 1918.

All briefs to be in the form of personal letters to The Etude and no brief to be longer than 500 words.

Vituperative, irrational, fanatical answers will not be considered. The Etude wants the sane judgment of as many of its readers as possible.

In presenting the Prize letters in The Etude The Etude will withhold the names of the prize winners if desired.

The number of replies pro and con will be counted and the number given in The Etude. If you are interested and do not care to compete for the prize you are requested to cast your vote, “yes” or “no.”

Letters for this Contest must be addressed to The Etude “Richard Wagner Trial” Philadelphia, Pa.