By Carl W. Grimm

If beauty depends upon natural laws, then the ugly also must depend upon them. At present, there seems to be taking place a reaction from the pursuit of the beautiful to that of the ugly. It is not our intention to throw stones at anyone who invents a new harmonic succession, or employs a chord till now unused, but in their quest for untried chords and horrible combinations many composers of to-day prove that they incline more to the bizarre and harmonically sensational than to the expression of great musical ideas. They are not imbued with that spirit which animated Wagner to write to Schumann: “I see what you are aiming at, and I assure you, it is my aim too, it is the only salvation: ‘Beauty.’”

The advocates of the newest music claim that “modern life vibrates with all kinds of noises, music therefore must render this sensation.” With these noise-makers, dissonance has become an end in itself. They enjoy hearing their freak music much talked about and often accepted for a phase of true music; they assert they have arrived at the end of the musical road. It is amusing to note that they do not agree among themselves. One of the boasting manufacturers of great “smashing and distorted chords” and discords sundered into parts, said of Schoenberg, “He is all brain, no spirit. His music is mathematical; he does not feel it.” We agree that all freak music is mathematical and never was inspired. There is an underlying basis for all methods of composition, and this basis can be formulated. Some music makers “come in a night and pass in a night.” They may be active for a decade or more, but because they are the expression of a passing fad they are doomed to oblivion.

That, such crazes must have existed before, can be gathered from the following words of Mozart: “Truth in all things is no longer either known or valued; to gain applause, one must write things so inane that they might be played on grind-organs, or so unintelligent that no rational being can comprehend them though on that very account they are likely to please.”

No Chance in Harmony

Strictly speaking, a musical composition is only formed out of tones, because the tone-world has its own natural laws. It must be accepted as a fundamental truth that certain chord successions and certain arrangements (positions) of the tones of chords will always produce certain effects. Consequently there must be uniformity in the tonal world, and laws governing it. Every effect is the result of some cause. There is no chance in harmony.

Conceiving the tone-world as a grand unity, possessing a rational order in all the variety of chords and their changes, and accepting the idea of uniformity of the mind, we must admit a co-ordination, selection or intention in the composition of all art-music. Regarding the technic of composition, Wagner wrote: “The technic of composition is the joint property of artists of all times, one inherits it from the other, every one increases it as well as he can.” We will add that harmony is nobody’s arbitrary invention, no gift from above, but the slowly formed concretion of effort: it is a gradual growth. Harmony is never stationary, but always in process, and naturally a process from simple to more complex.

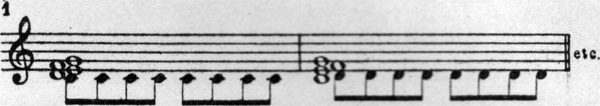

It is certainly instructive to read in a letter to von Bülow the confession of Wagner, “That since his acquaintance with Liszt he had become an entirely different fellow as a harmonist.” Liszt made many innovations in harmony and was the first to divulge the endless varieties and possibilities of the augmented triad and its whole-tone scale. He did not chance upon them accidentally, but tested his new harmonic material. Liszt even foresaw and despised the technic of our “futurist” composers, who believe they have reached the goal of music when they use in one single chord the twelve tones of the chromatic scale, and then clamor for quarter, third and other tones! In a letter to Ingeborg Stark (Summer 1860) Liszt wrote “The existing elementary exercises of the piano methods,

which are of a sonorousness as disagreeable as they are incomplete, ought to be replaced by this one,

which will thus form the unique basis of the method of harmony—all the other chords, in use or not, being unable to be employed except by the arbitrary curtailment of such and such an interval.

“In fact it will soon be necessary to complete the system by the admission of quarter and half-quarter tones until something better turns up!

“Behold the abyss of progress into which the abominable Musicians of the Future precipitate us!

“Take care that you do not let yourself be contaminated by this pest of Art!”

In a letter to von Bülow, Wagner criticised in the young composer’s Phantasie certain “unwarranted, rough and consequently cheap chord successions.” Wagner always aimed at harmonic euphony, and how particular he was in this may be gleamed from the fact that he wrote one chord succession in “Parsifal” over thirty times before he was satisfied with it.

In spite of his exalted position as a creative artist, Wagner always displayed a great interest in educational and technical problems, which many lesser composers consider beneath their notice. Just six days before his death he wrote a letter to the theorist Tiersch. These remarks ought to dispel the idea that great composers do not think about the technical problems of their art; their aim is perfection and beauty, and it is beauty that charms the world and lives forever in music.