Edited by LOUIS C. ELSON

Always send your full name and address. No questions will be answered when this has been neglected.

Only your initials or a chosen nom de plume will be printed.

Make your questions short and to the point.

Questions regarding particular pieces, metronomic markings, etc., not likely to be of interest to the greater number of Etude readers will not be considered.

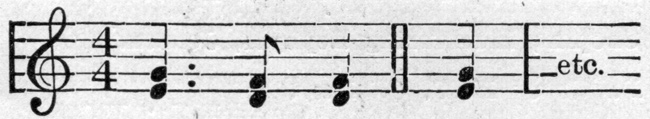

Q. Why does the fourth beat occupy a measure alone in the following? (M. W.)

A. The fourth beat does not occupy a measure alone in this case. The two vertical lines between the third and fourth beat do not mark a measure, but show the end of a phrase. You will find numerous illustrations of this fact in any hymn-book. Very often there is a broken measure at the beginning of a piece, in which the fourth beat might occur alone, and in that case the last measure would properly have only the first three beats. But there is never a broken measure in the middle of a piece, even though phrase bars or repeat bars are used. If any piece begins with an incomplete measure the last measure of that piece should also be incomplete and the first and last measures, added together, should make one complete measure.

Q. Is music a “gift” or is it something which anybody can acquire if they will. I have heard it said that even composers often write music without having studied theory to any extent, while many musicians who know all about harmony, counterpoint, etc., arc unable to write satisfactory music. What is the explanation of this? (L. H. P.)

A. Taking the last point first, it is quite true that many musicians who know all about harmony, counterpoint, etc., are not able to write satisfactory music. But that is their own fault; they lack inspiration. As for men who have never studied theory and the other branches, it is not probable that their efforts at composition would ever amount to much. It takes little or no education to reel off the popular rag-time, but for more serious work one must follow at least some of the branches of musical study. An important feature in the training of composers is a musical atmosphere during childhood. Of course, one cannot “make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear,” and music is decidedly a “gift;” but it must be increased by use, like the talents in the hands of the faithful stewards. Some composers are able to educate themselves. Elgar, for instance, after purchasing a new score, would stuff his pockets with bread and cheese and go out into the fields to study his treasure. As a training in form and orchestration he used a Mozart symphony for a model, and wrote one of his own with the same number of bars in each theme. But the greatest natural genius (after Bach, that is) was undoubtedly Schubert. One of his teachers said that he never could tell Schubert anything that the latter did not seem to understand already. Yet even Schubert felt the need of study, and just before his untimely death he had made arrangements for lessons in counterpoint. Wagner was another largely self-taught genius. His stepfather, dying, wondered if the boy’s strumming a tune indicated a possible talent for music.

Q. Is there any rule regarding the duration of a pause? Recently I heard a vocalist sing a familiar song, and he made it sound quite different by holding on to some notes for a great length of time while he sang others quite fast. Is it artistic to do this? He was much applauded. (H. K.)

A. There is no absolute rule regarding the duration of a hold or pause. Its length varies with the character of the music. When over a long note, as at the end of each phrase in a hymn, the note may be sung at less than double its face value. But a hold over a short note may increase its value several times. Thus Beethoven has a hold over a sixteenth note, which makes it about equal to a quarter note in value. The length of a hold or fermata may be influenced by the words lunga (long), piccola (little), G. P. or Grosse Pause (great pause), etc. But in the absence of these words the performer must use his own judgment. It is never artistic, however, to exaggerate the effects too greatly.

Q. I have heard that there is or has been such a thing as an enharmonic organ—that is, an organ with more than twelve keys to the octave. Is this possible? (W. P.)

A. As the present writer has not only seen it, but played it to some of his pupils, its existence is not only possible, but actual. Its scale is not our equally tempered one, consisting of the twelve equal semitones introduced by Bach; but it uses the so-called “scale of nature,” which Pythagoras based upon the mathematical divisions of a stretched string. In this scale a sharp is lower in pitch than the flat of the next higher note, so that more than twelve keys are needed for the octave. From seventeen to twenty-four have been used. The scale of nature sounds strange in comparison with our equal semitones, but it exerts a great charm after one has become used to it. Owing to the different size of its whole-tones it does not admit of much modulation; so a separate keyboard is needed for each key. It was this lack of modulatory possibilities that caused the scale of nature, even in a modified form, to fall into disuse when the scale of equal semitones was brought into use. Bach, in the first volume of his “Well-tempered Clavichord” (1722) first brought the “tempered scale” of twelve equal semitones into practical use, but Willaert fought for something of this kind even in 1550, while Andreas Werckmeister, born in 1645, gave a mathematical exposition of the tempered scale before Bach employed it. Nevertheless, it is to Bach that we really owe this musical Declaration of Independence. He practically announced that “all keys are created free and equal” in 1722, and repeated the assertion in 1742, when he composed the second volume of the “Well-tempered Clavichord.” (S. D.)