By ELLEN VON TIDEBOHL

[Editor’s Note.—Whether the popular prophecy that the music of the future will come from Russia is fulfilled or not, the musical accomplishments of the country which covers far more territory than any other in the world have been so astonishing that the musical world is looking to the land of the Czar with eager interest. The writer of this article has long been a resident of Russia. She is a close observer and most interesting writer. We are sure that our readers will be glad to know something of the part women have had in Russian musical development. In the March issue of The Etude M. S. Rachmaninoff, under whose supervision all the conservatories of Russia are conducted, gave our readers some splendid opinions upon piano playing.]

In the eighteenth century, while the cultured nations produced works by great composers, such as Bach, Gluck, Handel, Haydn, Mozart and many others, the recognition of music as an art, in Russia, had scarcely dawned, and its right to occupy an important place as a means of educating and raising the nation was hardly recognized.

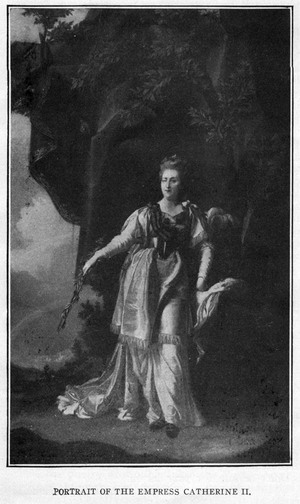

The initial step in creating a scientific basis for music was taken by a highly gifted woman, the Empress Catherine (1762-1788). Although she herself did not care much for it, still she recognized its power, and invited illustrious musical men from abroad to educate the Russians. The most talented young men were sent to Germany and Italy, at the public expense, for their musical education. Bortnianski, the first Russian composer with contrapuntal knowledge in the realm of church music, was one of these. He regulated the liturgy chants according to the rules of harmony.

The court of the Empress hastened to show interest in music. The nobility having their serfs, whom they could treat as slaves, ordered several of them to study music and play different instruments, in order to have their own orchestra. Teachers for them were brought from abroad.

We can scarcely believe that these rude laborers from the fields and forests could play symphonies and other orchestral compositions. At the present time, in noblemen’s country houses, there are sometimes to be found copies of very serious musical works, which were once played by the orchestras of their serfs. The programs of the performances, which have by chance come down to us in this way, include compositions of great composers.

The Empress Catherine II went further in her desire for musical education; she established girls’ schools, called “Institutes,” for the daughters of the nobility, where the study of music was obligatory. Therefore, it was the aristocratic ladies who were really the first to introduce the art of music in the country by performing standard works, both in the family circle and in society, and singing nursery songs with their children.

Many of the well-known native composers and musicians had as their first music teachers their own mothers. With her receptive soul the Russian woman thought deeply, cultivated the higher senses, penetrated into the mighty depths of the composer’s mind and, no doubt, had a great share in the work of evolving local music and developing the national artistic tastes by the interest she evoked in her hearers, thus swelling the members of lovers of music.

John Field (1782-1837) came to Russia (1822) and lived, until 1837, in Moscow, where he died and was buried. This well-known composer of the lovely and charming nocturnes, and a pianist of great expression, had the daughters of the highest families in Moscow as pupils. There is no doubt that he knew well how to develop and form out the latent talent in his pupils by his strict instruction, but, as it was not the thing for a lady of good family to appear on the stage, his pupils could not become professionals, so all we know is that several of them charmed Moscow society by their playing.

Adolphe Henselt (1814-1896), a composer of great musical value, and a distinguished pianist himself, settled in Petersburg in 1838. He became the examiner of music of the “Institutes” for the daughters of the nobility throughout Russia. It was a position of great responsibility, but he fulfilled his task with scrupulous conscientiousness and perseverance. He tried to impart to pupils the fundamental principles for the correct performance of music, wishing, above all, to lead them to a right comprehension of art.

Every year a great number of pupils at these “Institutes,” on finishing their education, went to different parts of the extensive provinces of Russia, thus scattering broadcast melodies and songs. “And the men?” you ask. There were some of great distinction at that time; but they were exceptions, for the boys were not forced to study music, and they only picked it up when their exceptional gifts inclined them in this direction.

THE FATHER OF RUSSIAN NATIONAL MUSIC.

The greatest of these composers was Michael Glinka (1804-57), called the father of the national Russian music, who took subjects for his operas from Russian life, Russian melodies for his songs, basing them all on contrapuntal rules, on which later was built up a music of an entirely Russian character. His successors followed in his footsteps with Balakireff and Dargomyjeski at their head; they were Borodin, Cesar Cui, Moossorgski, Rimski-Korsakoff and many others, a circle of broad-minded, liberal men, who had their own aesthetic ideals and chose realistic subjects employing the melodies of their national songs.

The interest in music increased with the appearance of these composers. Nevertheless, this art still remained a kind of luxury, a thing of joy for rich and fashionable society. The task of giving to music its high significance and right value as a means of culture and progress was undertaken by the two brothers, Anton and Nikolai Rubinstein.

With their large souls, their wide outlook on life, they knew what the people wanted, and all their energy was concentrated on organizing societies for musical performances, conservatories and music schools throughout Russia, thus affording an opportunity to every one of acquiring musical instruction. Nevertheless, they would never have attained the desired result if they had not been helped by a woman!

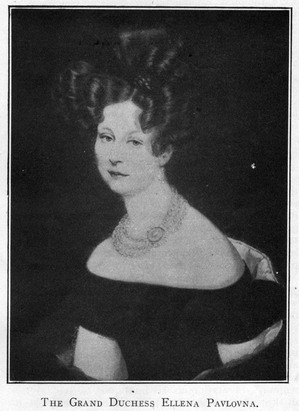

The Grand Duchess Ellena Pavlovna, with her influence at the Court in 1859, obtained permission to found the Imperial Musical Society and the Conservatories with a subsidy from the Government. This was just half a century ago (1859). That was a time when the bureaucracy was even stricter than at present. No private schools, scientific societies, etc., etc., were allowed without the special permission of the Government, and all kinds of difficulties were put in the way of obtaining permission for any enterprise. And even when permission was granted the Government reserved the right of controlling them and repressing anything that they found liberal or advanced in such enterprises.

The Grand Duchess Ellena Pavlovna, by birth a princess of Würtemberg (1814-1882), was married to the Grand Duke Michael in Petersburg, 1834. This cultured woman, with great largeness of heart, was always striving to do noble things in the noblest way, patronizing every kind of scientific and artistic institution. With her help the brothers Rubinstein achieved great results. The Imperial Russian Society was established in 1859, and began its activity by giving large symphonic concerts.

The Conservatory of Petersburg was inaugurated in 1862, and was managed by Anton Rubinstein; that of Moscow, in 1865, by Nikolai Rubinstein. He was as great as his elder brother, but the world knew him little, as he gave up all his time to Moscow, bringing music there to a high state of development. Let us give a glance at the mother of the Rubinsteins, who also had her musical duties to perform. Although they were modest ones, yet they required courage! She was the first music teacher of her sons, and, recognizing their eminent talent, did her best to develop them properly. She herself had passed her youth surrounded by wealth, but on the death of her husband had to suffer want and was obliged to gain her living by giving music lessons. It was not an easy task to bring up and educate such talented boys properly.

Death came to Nikolai Rubinstein just at the period of his greatest strength and activity. He was a man who stood quite apart, both in his artistic ideals and social life, but who, unfortunately, never lived to finish the task he had set himself in life. But one of his ends was attained when Moscow became the center of the musical movement in Russia.

Ruskin says: “It is a duty of people who continue to live after the death of a great man to accept his work with thanks and remembrance, not thrusting it aside, but by every means keeping it for generations yet to come.” After the death of Nikolai Rubinstein two women did this in the noblest way. In his memory Mrs. Zadouskaia gave a donation of about 100,000 roubles (about $50,000.00) as a fund for the Moscow Conservatory, the interest on which sum was to be devoted to helping poor students. The widow, Countess Odoewskaia, whose husband was a friend of Pooshkin’s and Glinka’s, made a magnificent present to the same institution by giving it in Nikolai Rubinstein’s memory her husband’s large library and a rich collection of stringed instruments of great value. Here, again, it was Russian women who did so much for the art locally!

From the very first the Moscow Conservatory was in a flourishing state. Even in the first year, 1865, it had good, experienced professors, with Nikolai Rubinstein himself at their head. This latter never spared himself in his work. Who were the first pupils in it? Only female students! Four of them were the first to finish their musical education in 1870, and at their examinations obtained the golden medal of distinction.

If we look over the first years of study at the Conservatory, we see that the number of female students was larger than that of men. Later on they were about equally balanced, and this state of things has continued to the present time. In pursuing our inquiry we shall divide the women who have helped towards the development of music into four classes: (1) Teacher, (2) pianists, (3) composers, (4) singers.

THE RUSSIAN CENTER OF MUSIC.

Moscow has become the center of musical evolution in Russia. The majority of the Conservatory students, on finishing their education, take up teaching as a profession. In all institutes, schools and private houses their number exceeds that of the men teachers. Women are even professors at the Conservatoire and Philharmonic School. About fifteen private musical schools have been established in Moscow, and are managed by women.

Music teaching by women in Russia is often a work of love. By its means she gets a deeper understanding into the inner life of the child in whom she wishes to develop a love of the art, and the results are sometimes wonderful. People are beginning to appreciate her work, to believe in her, not always preferring the master at a higher salary, whose musical attainments are but the same. The woman’s reputation as an intelligent active teacher in the sphere of musical advancement is fully established in Russia.

RUSSIAN WOMEN AT THE KEYBOARD.

The Russian women at the piano is most wonderful! Perhaps the impression she produces when playing lies in her Slavonian expansiveness of nature, in her lively temperament—the little girl even introduces into her playing something which touches the heart! Anne Essipow went all over the world producing great effect and boundless admiration by her poetical playing. She stands at the head of a countless number of women pianists pupils of the brothers Rubinstein, Safonoff, Leschetizky and many others. All the women pianists had more or less the same knack of producing passion and deep feeling from the instrument beneath their touch. This faculty doubtless takes its origin in the sensitiveness of soul and the richness of fancy which characterize the Russian woman.

WOMEN COMPOSERS IN RUSSIA.

It has been often said that a woman can never compose music! Nowadays this statement scarcely requires contradiction, as the contrary is so evident. Since serious musical education is within the reach of women, we see female composers appearing in the cultured nations—in France, Germany, Sweden, England, etc. It was Russia who led the way! You will find about fifty names of native female composers in the Russian catalogs of music. Several of them belong to the time of Glinka, others to the second half of the nineteenth century, and to our own days. There is a certain dilettantism in their compositions, in their romances, cantatas and piano pieces of a sentimental, romantic character. The song of the Countess Kotshubey, with the line:

“If he only could know!” had in its time a great run, was performed at concerts and was turned into a piano piece with variations by Ad. Henselt, which was proof enough of its musical value.

The poet Lermontow, who passes for a Russian Byron, was read and enjoyed by Russian women. One of his poems, “An Angel Flew Across the Midnight Sky,” was set to music by Olga Suchorukowskaia.

Another, “I Pass Along the Road Alone,” by Elisabeth Shashina; both of deep melancholy. They were sung and known all over Russia. Adelina Patti, during her stay in Russia, often performed at her concerts the song of Elisabeth Tarnowski, “I Remember.” Mme. Serow composed an opera, “Uriel Acosta,” with large choruses and orchestral setting.

These few examples of women composers at a time when Russian women had not yet received any serious musical education is proof enough of their productive gift in composing. Time will show what she will achieve in the future in this sphere!

RUSSIAN WOMEN VOCALISTS.

Dramatic gifts in conjunction with vocal art and musical talent make of the Russian woman a real born opera singer. There was a time in Russia when only Italian singers were admitted to the Imperial opera houses, when Italian music alone was listened to. Then Glinka appeared (1805-1857), the father of Russian music, of real national melodies. He composed operas, which necessitated employing Russian artists for their true interpretation. The number of Russian singers increased considerably at that time. Daria Leonowa was one of the first who excited great interest. She was the daughter of a serf, who was fortunate enough to escape from his autocratic master and started in business in Petersburg, which brought him in a moderate income. The artistic talents of his daughter were apparent from her earliest years. With the help of powerful protectors she entered the Imperial Art School, where she was heard by Glinka, who immediately made her a pupil of his. She had to sing the first roles in his operas. Her part in the development of Russian music lay in her showing the world that the Russian woman could be an artist in the full sense of the word. She went through Siberia to China and Japan, where she was the first European artist to win an audience. She made concert tours through Russia, with her friend, Modest Moussorgski (the composer of the opera “Boris Godounow”), introducing into the most remote spots of her country a fresh stream of art and melody. She died in 1892. Her “Mémoires” are full of interest, as she relates all her experiences and gives a brilliant and witty account of her time.

The limits of this article do not permit the enumeration and description of the great wealth of talented people we have had on the stage. I need only add that several of these great women singers were happy enough to be the source of inspiration to great composers, who wrote and dedicated their works to them.

At the present time the opera houses have many women singers of great talent. The Conservatories in Russia produce every year a considerable number of well-trained singers. Russian women, like the men, have won for themselves an assured position in the art world, and can now make free use of their gifts.