By EDWARD BAXTER PERRY

There are very few of

Liszt’s compositions which are technically within the possible reach of the average piano student,

none which may be called easy, but there is a very limited group of much prized, much used, well-nigh threadbare works of this “wizard of the piano” which forms a part of the working repertoire of every teacher and serves to introduce the pupil to the peculiar style and special technical difficulties common to

Liszt’s productions.

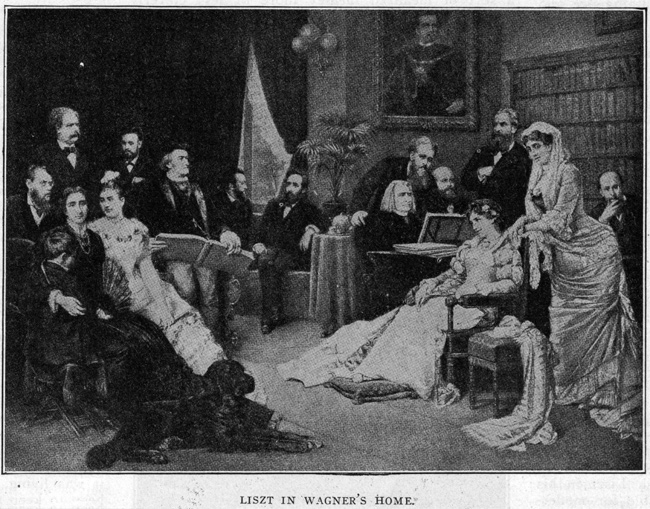

This interesting picture shows the great Hungarian pianist in the home of his son-in-law, Richard Wagner. Cosima Wagner, Liszt’s daughter, sits at the left of the picture with her arm around her son, Siegfried Wagner. On the wall hangs a portrait of King Ludwig, the fanatical Royal Patron of Wagner. It is said that Wagner frequently took his compositions to his greatest friend, Liszt, in order to hear how they sounded, since the great operatic composer played very indifferently.

As intimated, they are not easy.

Bülow once said, very aptly of

Liszt: “The rest of us

overcome difficulties, he never found any.” As a consequence he has little regard for the mechanical limitations of other players.

But the works referred to are possible for advanced students. The one oftenest seen on programs is the “Soirée de Vienne” No. 6.

The name signifies evenings at Vienna, and one piece is an elaborate setting for the piano, of one of a set of simple, graceful, charmingly melodious waltzes by

Schubert, once much in vogue in the aristocratic circles of that second Paris, as dance music.

These waltzes by

Schubert, though simple and unpretentious in form, give fullest expression to the half coquettish, half tender mood of the dance in those early days when the waltz was young and still possessed the charm of novelty; also to the graceful, yet vivacious, step and gliding, circling movement which they were written to accompany.

They are full, too, of danity (sic) suggestions of those elegant Viennese drawing-rooms, the sparkle of lights and jewels, the fascination of bright costumes, of shifting, kaleidoscopic colors, of the flutter of laces and ribbons and the witchery of smiles and glances.

IN A VIENNESE SALON.

This particular waltz, in

Liszt’s arrangement for the piano, assumes the proportions not only of a full-developed and well- rounded concert solo, but also of a complete and quite elaborate picture of a ball-room scene, drawn with the distinct personality of at least two of the dancers clearly portrayed in the introduction, with its two strongly contrasting themes. The first, a pompous passage in octaves and chords, seems to present the lordly, self-important cavalier in all the splendor of uniform, gold lace and orders, an officer of the Imperial guard, perhaps, stalwart, stately, assertive, more than sufficiently impressed with his own dignity, and the honor he is conferring upon his prospective partner; while she, a dainty, exquisite Viennese belle, a thoroughly equipped coquette, fully mistress of herself and the situation, is symbolized in the airy, capricious second theme. The two pictures are as clearly drawn here in tone as they could be on canvas by a master painter, and the individuality of each and the marked contrast between them must be strongly emphasized by the player. Then comes the alluring but simple little waltz practically as

Schubert wrote it, after which the waltz melody is repeated entire, but this time half disguised and greatly enhanced in beauty by a continuous series of delicate, intricate embellishments flowing around and among the notes of the melody as light and transparent as a fall of the finest lace, or the sunlit spray of a fountain.

HOW TO PLAY THE WALTZ.

When played the melody should remain distinct to the ear, with all its rhythm, accents and phrasing carefully preserved and apparent through the silvery ripple of the embellishments, like a fair face through the fluttering folds of a delicate veil. The effect, when properly produced, reminds one of that famous statue of the veiled bride, chiseled from a single block of marble, in which every line of the perfect form, every feature, and even shade of expression, of the lovely face is clearly visible through the fine meshes of the long flowing bridal veil which drapes the whole.

The composition closes with a clever Coda in which the waltz theme and the light motive of the lady are both utilized, and which also includes one of the long, tricky, chromatic cadenzas, the despair of young players, so common in

Liszt’s works.

LIEBES TRAUM, No. 3.

LIEBES TRAUM, No. 3.This is one of the very few original compositions by

Liszt which are at all available for students, hence is especially valuable to the teacher.

It is one of a set of lyrics for the piano entitled “Liebes Träume” (love dreams) in which

Liszt endeavored to express in this musical form—precisely as a poet might have done in a group of sonnets—his idea of the different kinds and phases of human love, as experienced by various individuals, or types, modfied,

(sic) in each case, by the divergencies of temperament, education and environment.

The No. 3 in A flat, which is the best known of the set, deals, according to

Liszt’s own statement, with the love of a mature man in the emotional vigor of his prime, a man familiar with life’s vicissitudes, its struggles and disappointments, its transient joys and fleeting hopes; a man tempered in the fires of experience, hardened by the constant buffetings of fate, yet preserving through all, in the secret temple of his inmost heart, a clear and deathless votive flame on the altar of his ideals. He loves with all the strength of his being, intensely, profoundly, passionately, yet with a certain grave reserve, a stern, self-reliant dignity, a strong, restraining grip on himself, determined that the tidal wave of passion surging about him shall not overwhelm his will or disturb his mastery of the situation. This intense, ever-renewed struggle between the raging tide of emotion and the rockof dominant will is the fundamental idea of the work, its esoteric significance, so to speak, but is an element not always grasped by the casual listener.

Superficially considered, the composition is a love song without words, mainly for baritone voice, cast in the form of a serenade, with harp or guitar accompaniment.

In the last repetition of the melody, in the soprano register, is introduced the suggestion of the soothing, tranquilizing influence of the feminine element.

Twice in the course of the work the melody is interrupted by a brief interlude between the verses, as it would seem, giving us a fleeting glimpse of the physical environment, a hint of the summer night in which the singer stands—the summer night with its hush and mystery, its subtle perfumes and vague whisperings, its wavering shadows and half-revealing star-gleams and the sense of indefinite longing and expectancy, which are the very breath of the summer night.

The work closes with a passage of soft,sweet, restful harmonies, a sigh of content in the final fruition of love’s dream.

The player should avoid the common mistake of accenting the running notes of the accompaniment in triplets instead of in groups of six as intended, which destroys the effect and their proper rhythmic relation to the melody.

CONSOLATION, No. 6.

This is an original composition from his pen, of moderate difficulty and possessing much simple melodic charm, which, by its grave, tranquil mood and earnest, devotional spirit, appeals to many, especially thoseof a religious turn of mind. It is one —and probably the best one—of a set of piano pieces entitled “Consolations” which were written, with many other more pretentious works—all of a distinctly religious character—during a peculiar episode in

Liszt’s varied and erratic career.

In 1856, tired of the world, its cloying successes and pleasures, its exhausting, unsatisfying excitements and dissipations, and under the domination of religious enthusiasm—very genuine while it lasted—

Lisztabandoned for a time his phenomenally brilliant artistic career before the public and retired into monastic seclusion of the most strictand rigorous type in the Vatican at Rome, where he was the honored guest of his holiness, the Pope, andfor five years devoted himself to religious study, meditation, devotional exercises and the creation of serious compositions based upon religious themes, many of them texts or incidents from the Bible, others upon spiritual experiences of his own.

Some of his best original works date from this period. (It was at this time he received the title of Abbé.) The “Consolations” were written at that time. They are small, comparatively unimportant productions, but are of considerable intrinsic beauty and are interesting because of the peculiar conditions under which they were written and of the unusual spirit they embody. They are especially valuable to the student in that they afford a glimpse into that phase of the composer’s life and experience.

The No. 6; which is the most familiar, expresses a tranquil, contemplative twilight mood, the welcome repose of a soul that has found rest and peace in the Faith after the storms and struggles and feverish agitation of a strenuous and not wholly sinless life.

It contains certain hints and echoes of bygone tempests, of doubt and rage and questionings, but softened and subdued like the sound of a distant sea, sobbing itself to sleep in some sheltering cave as the hush of evening falls after a wild day of futile fury. But the idea which forms the keynote of the work is final and complete reconciliation.

TRANSCRIPTIONS OF SCHUBERT’S SONGS.

Among

Liszt’s most valuable contributions to pianoforte literature may be classed his masterly arrangements, as piano solos, of a large number of

Schubert’s songs. Some of the most famous of these, like “Der Elkönig,” “Auf dem Wasser zu Singen,” “Gretchen am Spinneade” and others, are far beyond the reach of the student and only available for a concert pianist. But there are a few equally beautiful, though in a more quiet vein, which may be safely attempted by fourth and fifth grade pupils, and furnish excellent studies in tone production and phrasing. First among these is to be mentioned

Schubert’s world-famous and immortally lovely “Serenade,” every measure of which is replete with exquisite tenderness and idealized passion. It is a love-song of the warmest yet purest type, which will speak to the hearts of all lovers in all lands and in every age as long as love endures and music remains its most perfect and appropriate language.

This will prove an invaluable study for all who recognize the fact that the imagination and the emotional capacity of the player must be developed as carefully as his muscles.

It cannot be too frequently repeated, or too strongly emphasized, that three factors go to the making of the artistic pianist—hands, head and heart; or, in other words, technic, intelligence and emotion.

This composition presents one serious difficulty to the young player, viz.: the old puzzling problem of playing two notes against three with smoothness and accuracy in adjusting the accompaniment to the melody. It is not continuous, but occurs occasionally all through it, which is more confusing; but it can be solved with careful and intelligent study and is good mental training—as much so as a problem in algebra.

“DU BIST DIE RUH.”

This is a charming and comparatively easy lyric from the same collection of

Schubert songs transcribed by

Liszt. It also is a love song, but of a tender, reposeful character in which the beloved is apostrophized as the embodiment of rest and peace, the solace after pain, the calm after storm, the twilight dream of a quiet heaven after a day of earth’s heat and hurry and fretting turmoil.

Both melody and accompanying harmonies are wonderfully expressive of this soothing, tranquil mood—the very essence of perfect trust and ideal devotion. It is singular that this exquisite little work is so seldom used. It should be familiar in every studio.

“THE EVENING STAR.”

Another beautiful love lyric which

Liszt in his piano arrangement has made available for moderately advanced players is this “Evening Star” aria from

Wagner’s opera of

Tannhäuser.

It is one of several songs in praise of love sung by the assembled minstrels in competition for the prize at the famous music festival at the Wachtburg which is used by

Wagner as the central episode of the opera. Each singer treats the great theme of human love from a different standpoint, dilating on the special phase of the passion which most appeals to him, and the various expressions of the same general idea make of this scene a profound psychological study, and one of the ablest manifestations of

Wagner’s colossal genius.

In this “Evening Star” aria love is extolled as the highest and purest sentiment of the heart, enshrined within a sacred temple, remote from all selfish and earthly considerations; a self-forgetting, self-abasing reverential devotion to be guarded and cherished with a sort of religious ecstasy unalloyed by even a trace of personal desire.

The lady is symbolized by the bright but unattainable evening star, the guide and inspiration of the singer’s existence.

The melody is for baritone voice, rich and full and warm, but subdued and dignified, a wonderfully accurate expression of the intended mood.

It is, of course, accompanied by the harp, as was the case with all the songs of the minstrels or minnesingers of that early time, and the harp effects are simulated, or, rather, literally reproduced in the piano accompaniment.

“FANTASIE FROM RIGOLETTO.”

Every teacher knows the facile and rather cheap possibilities for display afforded by this old—not to say hackneyed number—once a great favorite in the concert room.

Any girl in the fifth grade, with lively fingers and a supple wrist, can scrabble through the brilliant runs and toss off the octave passages with which this work is so lavishly decorated in a manner to tickle the fond vanity of admiring parents and friends and to score a point for the technical training received from her professor, which appears to be—in the opinion of many—the sole purpose for which such pieces exist.

Nevertheless, in spite of the facility with which it lends itself to such use—or misuse—the work is not without real musical merit and beauty of its own special sort, worthy the consideration of the serious musician.

It is a fine specimen of a class of pianoforte works, now practically obsolete, but very much in fashion fifty years ago, namely, the fantasies on operatic airs, scores of which were written and played by most of the leading pianists of that earlier day, and which held a high place in popular favor.

The plan of construction was simple, demanding some ingenuity, but very little creative ability. It was merely to select and combine several of the most attractive melodies in a given opera, to form a sort of idealized medley more or less cleverly elaborated and highly embellished, according to the ability of the compiler.

The general form of the work and character of the ornamentations had usually no reference to any dramatic development or logical sequence of ideas, the aim being merely to present a series of pleasing melodies, decorated with pianistic fireworks.

In the hands of

Liszt, however, this class of composition, like all his transcriptions, received more than the usual care and finish. The melodies were better chosen and better arranged, with some regard for musical character and contrast. The harmonization was richer, fuller and more varied; the embellishments more significant and effective, the resources of the instrument more fully utilized, and the result was the production of something more nearly resembling a genuine art form.

The “Rigoletto Fantasie” is one of his best efforts in this line, and though its charm is somewhat superficial and sensuous, as must be admitted, it is real and lasting of its kind.

The work contains several fine bits of melody of the warm, emotional, Italian type, some telling cadenzas, and one superb climax at the close.

It is an effective concert number, possessing the much appreciated merit of showing for all—perhaps more than all—it is worth.

The opera of Rigoletto, one of the strongest productions of Verdi’s prime, is founded on that thrillingly, pathetically, tragic drama by Victor Hugo, “Le Roi s’ amuse.” The plot is intensely, though gruesomely interesting, but of questionable moral trend, as it exemplifies the triumphs of evil, and the useless, hopeless sacrifice of virtue and innocence.

Liszt has selected three of the most prominent and characteristic airs for the Fantasie in question: the pleading, seductive tenor air of the heartless, pleasure-loving duke; the recklessly rollicking soprano melody of the mirthfully vicious siren of the story, who is indirectly the cause of the final tragedy, and the impassioned contralto lament of the heart-broken heroine, ruined, forsaken, yet loving still with unreasoning devotion, who dies by the dagger of the hired assassin a voluntary sacrifice to save her unworthy lover, whose place she secretly takes at the fatal moment when her father’s just vengeance was about to be consummated; while the duke escapes, unconscious of his peril or her devotion—a flippant song on his lips.

These three representative and strongly contrasting melodies

Liszt has ingeniously woven together, closing with a stirring climax in which the last two referred to are combined as in the final act of the opera.

To appreciate fully the mood of each and to realize the dramatic situation, the student should read the libretto—or better—the drama by Victor Hugo.