SULTRY summer sunshine, like the dull days of winter, does not promise much work, neither is it a particularly inviting incentive to the student of music. The vacation period, with its enchantments of balmy weather, genial company, and lake, mountain or forest trips, is a welcome relief to us all, but it may also lead one into bad habits—nay, even jeopardize that splendid system which obtained during the fall and winter past, when to practice and study regularly became a pleasant routine, when daily progress was marked, ambition to improve was first and foremost, and diploma or certificate of work well-accomplished beckoned one onward, like a loadstone, to constant and well- directed endeavor.

Freezing the Tracks.

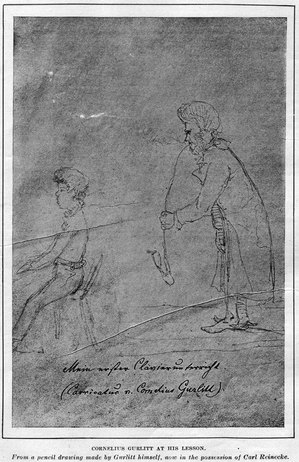

It is curious that mankind works best and is naturally most desirous to be busy when Nature is enjoying her beauty sleep of winter; and it is particularly significant that when Nature has grown and blossomed, has accomplished her regular miracle of reincarnation, that we crave a rest and a change. Especially so is this the case with the student, the professional man and the brainworker in general. There is a subtle instinct within us all to procrastinate when this vacation period comes around; and although the scheme of rest is all right, the trouble is that, whereas a well- stored brain can, and usually will, retain all its previous winter season training, actively-exercised fingers at keyboard or strings will not preserve their elasticity and shrewdness over a two months’ interim of rest. Trout rods, oars, tillers, and gun butts offer bad substitutes for finger exercises for the aspiring Liszt or Paganini; and to be away from one’s chosen instrument too long at a stretch is ill-advised, even though tired nature may demand a complete change.

Those deep, decisive steps we made during the winter months of activity can be blurred—indeed, almost entirely effaced—if we allow the sunny days of indolence to bask upon them too often in the fancied security of retrospection. It is well to keep them frozen firmly by a judicious use of artificial cold in the shape of a scale or two now and then, or an exercise, played with daily care, even if the means at hand are no better than the bottom of a camp kettle or a willow branch cut the length and weight of that fiddle bow left at home with your mittens and furs, which will not balance so well, believe me, next September or October.

Planting the Tracks.

Planting the Tracks.I suppose all of you flung your school books into the deepest corner of the closet or shelf after the June finals, when the warm dust called those racing bare feet down its inviting summer pathway, or Susie or Jack wrote you that “you simply must come to spend the vacation with them.” Nor was this at all culpable, for children need play, lots of play, and youth is the most precious playground of life; but school was meant not so much for actual use in after life as it was to assist the later development when we naturally come to specialize. Not so is the study of music. There we are already making our pathline of tracks which will remain firm and distinct, or fade and grow dim as we exercise care or fitfully neglect to do so. For, presuming that you are in earnest, your fingers or throat have no will of their own, being only the mechanical servants of your mind, and as such must be kept in the pink of condition all the time. You cannot throw them into the corner as you did that algebra or grammar, to be reopened in the fall at the next chapter. They are responsively learning, copying, good and bad alike, faithfully followed all the time, and their natural dexterity does not often lie in piano or violin playing; they must be memorized and rememorized in that direction constantly.

Fingers can be trained to do anything that is a physical possibility, but in order to keep them expert they must be trained ad infinitum. I do not mean that one should never cease, but on the other hand to cease practicing entirely or even for a month or a few weeks will develop a tendency to sprawl or kink up that is comically lamentable. Take your vacation; pitch in and have a lot of rest and fun, but—keep an eye out for a stray scale or exercise, every day if possible, and then while you are at it let that period be one of painstaking care and solicitude.

Prints of Youth Eternal.

Mind tracks do not melt easily. Our thoughts, from infancy up, were born mature, inasmuch as they, or at least their effects, are lasting. On the unspotted page of innocence many a thought of faraway youth has served the recollection of old age, emerging from its fifty or so years of seclusion as brilliant and distinct and fresh as though it had been born but yesterday. Shakespeare’s genius realized this in his account of the death of Falstaff.

Dame Quickly dismisses the deathbed scene of the ancient rake very shortly. “He babbled of green meadows,” quoth she. Poor Falstaff! After a life of dissipation, violent pleasures and violent troubles his mind wandered back to his early childhood, when, perchance at his nurse’s knee, his obedient, baby lips had repeated the magical numbers of the 23d Psalm, “He leadeth me beside still waters —He maketh me to lie down in green pastures.” In the purity of that once-upon-a-time the text had indelibly stamped itself and neither the whirl of men and women nor events could exactly erase its influence.

Strength in Coolness.

It is by no means stretching our simile to speak of snow as the best medium to indicate our path through life, for one’s best efforts musically are made when one is absolutely cool and collected. Too often we are fired with the enthusiasm of our own feelings and imagine that we are affecting our listeners likewise. Not so. On the contrary, the more self-contained you are and calculating, the firmer your hold will be upon your audience, because the more truthful you are the more powerful and expressive you become. Therein lies the great success of the playing of Jan Kubelik or Paderewski. You can no more be artistically perfect while swayed and biased by your own emotions than you can burn another’s hand by holding the match to your own finger. It is not necessary to do either. Rather hold the light between you where both may observe its beauty. Do not hug it all yourself. I have seen players swing and sway to the rhythm of their own music until they needed a straightjacket. One may be tender, you know, without being violently effusive—like the little girl who squeezed the kitten to death because she loved it so. Sane playing wins out every time and to be sane you must be cool as well as sympathetic.

Coda.

A lengthy vacation from any musical course is always dangerous, for with the mind relaxed careless habits in playing and thinking are easily acquired which are hard to eradicate, and there is always the worry of feeling that when you start in again in the fall your technic will be mad. “Life is fleeting and Art is long,” and, like tracks in the snow, we must firmly cross over the few years allotted to us upon which to stencil our progress. Like those footprints our best endeavors are more or less fleeting, since music is more of a recollection than it is a reality, depending upon the few moments while we are producing it for its influence upon those who hear it, and upon the attitude of those who are listening, largely for its success or failure to elevate and please.