Prepared by FANNY MORRIS SMITH

from the biography just issued by the Century Co.

Our library of books in the English language on music has increased greatly during the last twenty years. Letters, autobiographies, memoirs, and criticisms have multiplied in ever increasing progression; for the present epoch of musical development has rounded past its zenith and the stage of inspection and appraisement has long since been reached. But in the volumes poured forth in later years we have looked in vain for the fresh romantic spirit; the musical imagination, the spontaneity, which distinguished “Charles Auchester,” Mendelssohn’s Letters, or even that little classic of piano literature Amy Fay’s “Music Study in Germany.” The work from which we have been privileged to make some extracts “Theodore Leschetizky,” by his sister-in-law, the Countess Potocka, issued by the Century Company, is, therefore, a delightful surprise, full of witty anecdotes and genial reminiscence; we read it with avidity and arise inspired with its own enthusiasm. All the material in it is new; much of it surprising. It is a vivid picture of one of the great musical personages of the century just closed; it is more even than a delicious portrait of a personality famous for its fascination—a portrait, with all its accessions of surroundings—and perspective. The book stands on its own merit as a literary production. Leschetizky might be its hero conjured from the dreamland of musical romance, and it would still take its place as one of the most charming pieces of literature that has appeared for a long time.

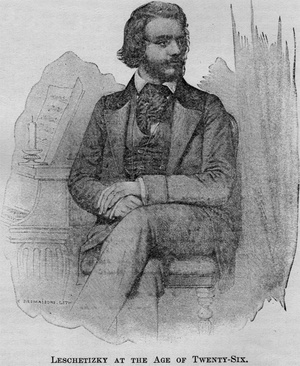

Theodore Leschetizky was born in the Castle of Lancut, 1831, the hereditary estate of the Potocki. His father, Josef Leschetizky, had studied law, but finally drifted into music as tutor of the children of Count Alfred Potocka. The charms of Thérèse von Ullmann, our hero’s mother, completed the tie which bound Josef Leschetizky to Lancut; the Potocki encouraged the union, and the young people were married and established in a wing of the Castle, where Theodore spent the early years of his childhood. At three years of age his playgrounds were, as he relates, “on the grass or gravel walks immediately under the windows of the rooms where the music-lessons and practising went on. I soon learned to distinguish between the playing of the two young countesses. They played selections from the works then in vogue, especially transcriptions and fantasies by Thalberg from the then very popular Bellini operas. When I was taken into the house, my little brain swarming with these melodies, I experienced a wild desire to reproduce them. This, however, was a difficult matter, as my father, fearing that I might be tempted to pound on it, regularly locked the piano when not in use, and carried away the key. The instrument was an old-fashioned upright clavecin, and I discovered that by drawing the green silk curtains that protected the lower mechanism, I could work the hammers from below and make the strings respond. Seated on the floor under the keyboard, I thus made my début and earned my first applause; for my mother’s heart was filled with joy at recognizing the airs that her little ‘Dorcio’ soon learned to pick out in this novel fashion. Seeing my eagerness, she finally persuaded my father to give me lessons. I was then about five years old, and my progress was so rapid that my father decided to bring me out, and I made my entrée in the drawing-rooms of the best families of the neighborhood.”

The charm of Leschetizky’s genius as pianist, composer, and teacher, has always been the highbred manner and refined imagination which characterized his musical expression.

The impressions received in the seigniorial surroundings of Lancut, where traditions and legends had become a part of daily life, have left their mark on Leschetizky’s mind and have affected his entire personality; and to them may in part be traced the formation of that spirit of the past without which no modern artist can lay claim to catholicity of thought or feeling.

As the child grew up his history repeats the usual experiences of the “Wunderkind.”

The paternal views were stern and uncompromising; unpleasant scenes frequent; cruel punishment, often blows, consequent.

For the most trifling offense, a spot on his clothing, a small negligence, the boy was sure of severe chastisement, and, revolting at continued tyranny, would fly to an obscure corner, there to weep out his sorrows unseen. If a visitor happened to call, the father, proud of his son’s talents, would go in search of him, and, finding him vindictively retrospective, drag him from his hiding place and cajole him into a better humor, trying by soft words and caresses to obliterate the sense of injustice from the offended child’s soul and rekindle therein the sacred impulse. The artist’s impulse was already strong. Dory was usually willing enough to play, and, in playing forgot his woes.

His father demanded several hours a day of conscientious, hard work, and required in all things a self-control far beyond the boy’s years.

Dory was allowed no toys, and his superabundant animal spirits were constantly and sharply criticised. Josef Leschetizky was not always just and seldom consistent. His narrowness excluded insight into childish needs, his constitutional dissatisfaction found vent in continual and bitter sarcasm. If his son, whose original talent developed early, seemed to be in the mood for composition, the father would decry his efforts, assuring him that it were far better to invest his energy where there was more hope of return; if, on the other hand, his books tempted the child away from the piano, he was subjected to such satirical remarks as, “I see! that is what is going to bring you bread and butter.” If, finally, Dory was particularly diligent in piano practising, the elder Leschetizky would exclaim in cutting tones: “That’s what one comes to when there are no brains. You play and play, and forget that without composition you will never be an artist.”

Leschetizky made his début at the age of nine, at Lemberg, where he played Czerny’s Concertino with orchestra under the baton of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart,—son of the immortal Mozart,—then director in Lemberg.

As Theodore’s technic developed, he seems to have felt the necessity of fresh stimulus. He says: “At the age of eleven I had conceived an ardent desire to meet the great pedagogue, Carl Czerny, of whom I had heard so much; and in the fall my father took me to play for him. I played Czerny’s concertino, and the so-called ‘Alexander Variations’ by Herz. My father had had lessons from the renowned teacher, so that I was well prepared to derive immediate benefit from his valuable instruction, and my new master seemed to take a lively interest in me. I went every Sunday to take my lesson. Czerny occupied rooms in a house on the Petersplatz. He was rather short in stature, with woolly hair and bright, expressive brown eyes, which fairly shone behind his spectacles. His was a high order of intelligence; he was deeply interested in politics, and spoke seven languages. Though of Bohemian parents, he was born in Vienna. Czerny was a pupil of Beethoven and Clementi, and, besides being himself an eminent pianist, was, with Hummel, at the head of the school of playing founded by Mozart.”

“His manner of teaching was somewhat that of an orchestral director. He gave his lessons standing, indicating the different shades of tempo and coloring by gestures. The chief aim of my father’s instruction had been the development of musical feeling and taste; Czerny insisted principally on accuracy, brilliancy, and pianistic effects. I played a great deal of Bach under him, some compositions by Alkan, some by Thalberg, and, above all, those of Beethoven. Czerny taught that Beethoven should be rendered with freedom of delivery and depth of feeling. A pedantic, inelastic interpretation of the master made him wild. He allowed me to play Chopin just as I pleased, and though he appreciated the great Polish writer, he sometimes said his compositions were sweetish. Again he would become enthusiastic, and say that they were ‘famose Musik.’”

The story of Leschetizky’s growth from boyhood to manhood must be left for the perusal of the reminiscences; but the moment when the young man— already a virtuoso—“found himself,” and realized the bent of his own genius, is too important to the readers of The Etude to be omitted.

Schulhoff.

It was at an evening reception given by Dessauer in honor of the artist Schulhoff, who had been so well received in Paris and whose concerts were announced in Vienna. “I well remember,” says Leschetizky, “that drawing-room, filled with musicians and critics, all expectation with regard to the artist of the day. He was, of course, asked to play, and acceded with charming simplicity. After trying the piano and preluding a little, he began a composition of his—‘Le Chant du Berger.’ Under his hands the piano seemed like another instrument. Seated in a corner, my heart overflowing with indescribable emotions as I listened, not a note escaped me. I began to foresee a new style of playing. That melody standing out in bold relief, that wonderful sonority—all this must be due to a new and entirely different touch. And that cantabile, a legato such as I had not dreamed possible on the piano, a human voice rising above the sustaining harmonies! I could hear the shepherd sing, and see him. Then a strange thing happened. He had finished, and had awakened no response. There was no enthusiasm! They were all so accustomed to brilliant technical display that the pure beauty of the composition and interpretation was not appreciated. It was the first time that an artist played small things in which mechanical difficulties were not evident. Dessauer, coming toward me, a slight sneer of disapproval on his face, asked me what I thought of it. Still very much moved, I answered: ‘It is the playing of the future.’

“Schulhoff’s playing was a revelation to me. From that day I tried to find that touch. I thought of it constantly, and studied the five fingers diligently to learn the method of its production. I practiced incessantly, sometimes even on the table-top, striving to attain firm finger-tips and a light wrist, which I felt to be the means to my end. I kept that beautiful sound well in my mind, and it made the driest work interesting. I played only exercises, abandoning all kinds of pieces, and when my mother advised me to go back to them, I only answered: ‘Oh, no! it is not ready—I shall not have it for three months.’ At the end of three months I went back to my work feeling less dry. I had attained my result.”

The reader will remember Leschetizky’s advice to his students; briefly: “Study piano-playing at the opera and concert, singing is the worm of musical execution.” As Liszt fired by the playing of Paganine retired to create for the piano the means of orchestral interpretation, so Leschetizky, obedient to the instinct of his race, worked in the opposite direction toward sympathetic and songful delivery, and lives to see the force of his genius stem the tide of “pianism” which threatened the existence of piano- playing as the vehicle of creation.

In Russia.

We must pass on to the advent of the now famous pianist at the court of Russia.

Anton Rubinstein had been occupying the position of Concertmaster at the court of the Grand Duchess Helen, sister-in-law to Emperor Nicholas. Deciding to go on an extended concert tour, he warmly recommended Leschetizky as his successor.

Among Leschetizky’s duties at the Russian court was that of directing the vocal studies of the Grand Duchess Catharine, daughter of the Grand Duchess Helen, and of Mlle. Anne de Friedebourg (Carlowna), one of the ladies of honor, a young woman who, (as his future wife) was destined to play an important part in his life. She was not beautiful, but there was remarkable distinction in her appearance and manners. She sang wonderfully. A pupil of Viardot, Garcia, her method was perfect, and as for the depth of sentiment she expressed, I can only repeat what Anton Rubinstein said: “That voice was a tear.” It was the grand duchess’ wish that her gifted young protégée should become acquainted with the songs of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, and others of the German school; and it was with great zeal that Leschetizky undertook his task. Friendship was the inevitable consequence of these studies, a friendship which, maturing into a warmer feeling on one side, was not to lead to happiness for either.

Leschetizky’s career in St. Petersburg was full of amusing episodes of this character, but we hasten to bring the various episodes before the reader.

Mme. Essipoff.

In 1864 a twelve-year-old girl was brought to the conservatory at St. Petersburg, a slight, nervous little person with expressive, green-gray and a precocious intelligence. It was Annette Essipoff. Her excellent ear, fine memory, and other marked musical gifts immediately attracted attention. She entered Van Ark’s preparatory class, and a year and a half later played a Beethoven sonata (C major, 2 Op., No. 2) at the examination held before the board. The grand duchess, presiding, armed with her inevitable crochet work, asked Leschetizky what he thought of Essipoff’s talent. “That little one has the very Old Nick in her,” he answered. “She will be a great artist.” Essipoff was promoted to Leschetizky’s class, and made rapid strides; though for a long time a shade of amateurishness, due to a lack of discipline, cost her master many a stern effort to overcome, and impeded her advance toward virtuosity. As an illustration of this may be narrated a short anecdote. In preparing the Chopin G minor Ballade for an examination, she had been hopelessly negligent in learning the notes; and, though she played the correct melodies and harmonization and maintained the proper rhythm, relying on her natural facility she gave the accompanying figures more as her fancy dictated than in accordance with the composer’s notation. This was really too much for her critical master, a boldness and impertinence deserving punishment, and rising in his wrath, he publicly threw the music at the discomfited girl, informing her that she was to consider it all over between them. Later, of course, he thought better of it; and it may be remarked here that almost all his gifted pupils since then have had at some time to go through a like dismissal, with the subsequent relenting.

A charming painting by Michel Stohl, representing Essipoff as she was at that time is still in Leschetizky’s possession. No longer the frail, nervous school-girl, Annette had developed into a lovely young woman. The firm, well-molded figure, the brilliant complexion, the bright eyes in the picture are those of a healthy, active, well-matured physical nature.

I believe that her great charm lay in her poetic interpretation. It was all so wonderfully shaded; indeed, the fine subtlety of her shading has excited the admiration of the greatest musicians; and besides this she had a great deal of verve and style. While it was passionate, she says herself that her playing was not particularly powerful at that time. Strength was a much later development; for loud playing had not been required of her, her natural quantity of tone being effective on account of her forceful contrasts.

I once asked Essipoff how she managed to play with such tiny hands, and she answered that they served her perfectly, that larger would be cumbersome. Her hand was strong and nervous, but neither soft nor white, like so many aristocratic hands that have never done anything for humanity. Raised slightly above the key-board prepared to grasp a chord, it strangely reminded me of an eagle’s claw.

The Countess’ reminiscences of Paderewski were equally interesting.

I remember the night that Leschetizky brought out his brilliant pupil Ignace Paderewski. His performance of an original theme and variations was not greeted with special favor. Indeed, some local musicians were heard to remark that the “young man did not seem to promise much.” But his keener master opposed envious criticism with the now unanswerable statement, “Ah, my dear, you will have to get used to hearing that young man’s name.” Yet, as he stood nonchalantly in the passageway, his tawny head resting against the wall, those who foresaw his great future were probably few.

He came to Vienna to study with Leschetizky in 1885. Of all his pupils, the master claims that Paderewski was the most docile. There was no remark so insignificant, no detail so small, as to deserve less than his whole passionate attention. In his two modest rooms in No. 46 Anastasias Grungasse (rooms which for motives of sentiment he retains on a life lease), with a slender wardrobe and scanty comforts, he patiently laid the foundation of his brilliant career.

Paderewski studied continuously in Vienna for two years. He received lessons from Mme. Essipoff and many from Leschetizky himself. These he took irregularly, sometimes one a week, sometimes two, and generally in the evening from seven to nine o’clock. After teaching for a year in Strassburg, he came back to Vienna for another season; but his lessons were interrupted by his concert engagements in Paris, Germany, and Switzerland.

Leschetizky’s opinion of his famous “method” will, be welcome to the readers of The Etude.

Speaking of the method himself, he says: “It can easily be described in half a page, but it would take volumes to give any idea of it.” As far as the position of the hand is concerned, it offers nothing strikingly different from the common practice of modern virtuosi—a rather low, pliable wrist, high knuckles, curved fingers with firm tips, light thumb, and accurate preparation in advance of all single tones, octaves, chords, etc. The peculiar excellence of his teaching consists, I believe, in the absolute obedience, the concentration of mind and purpose not only demanded but actually obtained from every pupil, the minute attention to detail and the patient reiteration of suggestion.

Altogether we cannot praise this unique little biography too highly. It cannot be spared from the book-shelf of either music teacher or music student, giving as it does a fascinating picture of one of the most interesting personalities in music.

Copyright, 1903, by The Century Co.