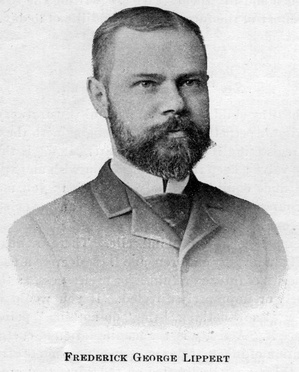

Frederick George Lippert, of Phoenixville, Pa., was born in 1851, in Leipsic, Germany. He grew up in a musical atmosphere, which developed in him early an intense love for music. He writes of himself: “When but a small boy, I was allowed, one Good Friday, to help with my soprano voice to swell the great chorus of 400 voices performing in grand old St. Thomas’ Church, under Carl Reinecke’s baton, Bach’s “Passion music according to St. Matthew,” from the same gallery where, more than a hundred years before, the immortal Johann Sebastian Bach himself used to preside at the organ. Here, too, I saw Franz Liszt conduct his oratorio, “Die heilige Elisabeth,” and every Saturday afternoon that I could free myself I came here to listen to the motet-singing of the famous boys’ choir of St. Thomas’ School under the direction of its venerable cantor, Moritz Hauptmann.”

After graduating from the preparatory school, Mr. Lippert went to Dresden. Here, too, he put himself in touch with a circle of music-loving people, central among whom was Edmund Kretschmer, court organist and composer of the opera “Die Folkunger” and many choral works, who, at the same time, conducted the academic glee club, “Erato,” of the Polytechnic students, of which Mr. Lippert was an enthusiastic member.

In 1873 Mr. Lippert came to this country, in which he has remained up to the present time. Mr. Lippert, assisted by his wife, some years ago founded the “Euterpean Club,” an organization for the cultivation of high class music, vocal and instrumental. During several seasons, the “Euterpean” recitals, held at the Phoenix Club House once a month, have proved a signal success, both musically and socially.

“Thou shalt not steal!”

It is sometimes charged by musical critics and lovers of the art that certain compositions, in whole or in part, lack the originality of invention which entitles them to be considered as free creations, or, using a more direct expression, that they are purloined from the works of other composers,—a practice commonly understood by the term, “plagiarism.” It will be found, however, that critics do not altogether agree on the definition of what constitutes plagiarism, because it is a relative thing, according to the standpoint from which it is viewed. It may, therefore, prove of some interest to inquire briefly into the nature of this practice; to define, if possible, its limits, and to point out when it is to be condoned and when to be condemned.

It is sometimes charged by musical critics and lovers of the art that certain compositions, in whole or in part, lack the originality of invention which entitles them to be considered as free creations, or, using a more direct expression, that they are purloined from the works of other composers,—a practice commonly understood by the term, “plagiarism.” It will be found, however, that critics do not altogether agree on the definition of what constitutes plagiarism, because it is a relative thing, according to the standpoint from which it is viewed. It may, therefore, prove of some interest to inquire briefly into the nature of this practice; to define, if possible, its limits, and to point out when it is to be condoned and when to be condemned.

It is much easier to raise the charge of plagiarism than to substantiate it. For are we not all plagiarists in our sayings and doings? Do we not, through early education and association, through reading, nay, through the visible example of our elders, imbibe ideas which we do not hesitate to express as our own? Do we not unconsciously reflect the opinion of our daily paper, whether in politics, sporting matters, the drama, art, or music,—little thinking that we are mere plagiarists of an editor who, in turn, may be plagiarizing some one else? We can not ignore the fact that, owing to our human organization, we stand on the shoulders of our fathers, just as they stood on those of preceding generations.

All knowledge is handed down continually by older heads to younger ones. In the world’s libraries are stored up the accumulated knowledge and experience of bygone generations and eras, furnishing us with innumerable suggestions. The easier the access is made

to the means of absorbing the ideas and opinions of those gone before us, the less frequent becomes real originality of thought and speech. The same is true of music. When we reflect what an immense variety of musical ideas the student has to assimilate in his studies, the wonder is not that there should be so much plagiarism, but that there is so little!

The old adage, “There is nothing new under the sun,” has a good deal of truth in it. This we realize when, in listening to a new work of music, we encounter ideas in it that seem quite familiar to some of us, because those ideas have dwelt, in a semi-conscious existence, in our brains before, without being given utterance by us. It is the prerogative of genius, to voice and waken to life what has lain dormant in the minds of the noblest and best of our race.

How a suggestion is sometimes taken up by a master mind may be shown by the following example: A Beethoven hears, somewhere in early youth, a folk song, leaving a faint impression upon his mind. Many years have elapsed, when the “giant” needs a theme for the andante of his Second Symphony (in D major). Suddenly that long-forgotten bit of melody rises up in his memory. It is seized and worked up into an immortal orchestral movement of transcendent beauty. Is there any one who would, for a moment, question Beethoven’s ability to invent a theme when he needed one? Was composer ever possessed of a more robust originality?

The identical old folk-song may have hovered about Moritz Moszkowski’s brain when he wrote his tender melody, “Deutsch,” in the suite, “Aus aller Herren Landern.” And yet, who would call him a plagiarist for that? Do we not admire Edvard Grieg for the use he makes in his compositions of his native Norwegian folksongs that supply him with suggestions for his melodies, and his harmonies as well?

What is it that makes Chopin, with all his elegant grace, so powerful, if not the fact that his art is the reflection of the innermost soul of the Polish race? Should we charge him with plagiarism because he worked into some of his “Valses” and into his First Concerto (in E-minor) little bits of Swiss airs which had delighted his ear? Certainly not. But where should the line be drawn?

When a composer appropriates a suggestion emanating from some outside source, and, after digesting it, so to speak, stores it away in his memory with the thousands of other ideas which he holds as his inalienable mental property, to be drawn upon at will; when, in the act of mental production, he searches the recesses of his memory for an idea that will meet the immediate want, and his mind then yields up that long-treasured impression which has become thought of his thought, must we not accord him the untrammeled use of such an idea, especially when he clothes it in his own language, his own musical coloring or harmony?

We claim that the adoption of an outside suggestion does not necessarily imply the lack of imaginative power in an artist. The important point, upon which the question of plagiarism hinges, seems to us to be this: If you prove yourself a master in the utterance of musical ideas, you may undertake to express any kind of an idea, whatever its source may be, so long as you handle it with a supreme command of the means of musical expression.

Did not Mozart acknowledge a debt of gratitude which he owed to Palestrina for suggestions received from his works? Did not Mendelssohn attest a similar gratitude with regard to Johann Sebastian Bach? Spohr and Gounod with regard to Mozart? Marschner with regard to Weber? Berlioz and Wagner with regard to Beethoven? and many of our living composers with regard to Wagner? Let it not be forgotten that all development in music is governed by the all-embracing law of evolution, and that every eminent composer builds upon the foundation prepared by his predecessors, taking up the thread where they have left it, to evolve the art-work one step further.

When Schumann introduces the “Marseillaise,” half disguised yet distinctly recognizable, into his “Faschingsschwank aus Wien,” just to poke a little fun at the Vienna police, which had forbidden that stirring air to be played within the Austrian capital; or when, as a personal compliment to his friend, Sterndale Bennett, he builds up the incomparable finale of his “Études Symphoniques” upon an English ballad in praise of Richard Cœurde Lion (sung by Ivanhoe in Heinrich Marschner’s opera, “Knight Templar and Jewess”), we pronounce such proceeding not only perfectly legitimate but highly commendable, because of its ingenuity and fitness. In a similar manner, we think Meyerbeer entitled to praise for building up his overture to “Les Huguenots” upon the great Lutheran hymn, “A Mighty Fortress is Our God.”

In all the cases cited so far the charge of plagiarism can not be sustained, it being evident that the design to appear as the originator of the respective air or theme was foreign to the composer’s mind. The case is different, however, when the composer would make us believe that he originated the themes or phrases which, in reality, owe their origin to some one else. Here, again, we distinguish between two categories: First, where the high grade of ability of the composer precludes the idea that he could not have himself produced what he borrowed, from reasons of convenience, elsewhere; secondly, where it is plainly apparent that the composer purloined a thing he was incapable of creating.

One of the most notable instances of the first order, in musical history, is afforded in the person of Händel. It can not be denied that this great master pilfered the scores of contemporary and preceding brother-composers for themes and suggestions. Yet, when we consider that there was, among the musicians of his time, hardly one who could express and clothe musical ideas in such masterful form as did Händel, and that he undoubtedly improved upon his models, we carry away from the study of his works the conviction that, had he so desired, he could have created original ideas in place of those borrowed,—a conviction inclining us to condone his offense, if such it must be called.

Among operatic composers of distinction, Meyerbeer has been very generally accused of the theft of the mental property of others. No less a one than Richard Wagner, his bitter antagonist, has, on that account, heaped abuse upon Meyerbeer in terms fitting for the most depraved criminal; but, we think, without sufficient justification. Meyerbeer was an eclectic, following no one school in particular, but ready to assimilate everything good, no matter where he found it. He was by no means scrupulous in borrowing ideas from the scores of great masters, living or dead. His “Robert le Diable” and “Les Huguenots,” as well as others of his operas, teem with passages that will convince the critic that Rossini’s “Tell,” Auber’s “La Muette,” Weber’s “Der Freischütz” and “Euryanthe,” and Beethoven’s “Fidelio” were too well known to Meyerbeer. But what of that? We owe the latter a lasting debt of gratitude for giving to the world a series of most effective and attractive operas which, to this day, despite the almost universal sway now held by the Wagnerian muse, have not lost their hold upon the habitués, be it in Europe or in this country.

If it be urged that Meyerbeer stole the theme for the trio of the Coronation March, written for his opera “The Prophet,” from a Mass by Schneider, a noted organist of Dessau, Germany, let us be thankful that by merging it into his opera he rescued a distinctly charming air from oblivion, and gave delight to thousands of lovers of music who, but for Meyerbeer, would never have heard it.

The question may be raised whether a musician in the act of composing is at all times conscious of the “whence” of the ideas crowding in upon him; whether he realizes fully when he is making use of an idea of some brother-composer. To answer this one would have to be himself a creator of music, and even then he could only speak for himself individually and not for others. Still, the inference would be that during the process of enthusiastic production the master-mind is prone to lose sight of petty considerations anxiously separating the meum and tuum.

So far we have considered the use of foreign ideas by those in full possession and command of the means of their art. But a wholly different aspect is presented to us when the composer does not possess technical mastery; when crude, commonplace detail characterizes his work, he being a mere tyro in his profession. To such a one the purloining of musical ideas from superior minds often becomes a trap, into which he falls; for what is not his own becomes easily apparent by the contrast it evokes when compared with the inferior product of his brain.

When we have unmistakable evidence that a composer has arrayed himself in a brother-composer’s cloak to cover his nakedness; when we feel that, without such help from outside sources, a production would be utterly without value and insignificant, then we feel called upon to enter a vigorous protest against such practice, and hesitate not to stamp the perpetrator of such an act as a bold plagiarist.

Still more reprehensible than the purloining of a phrase or “motiv,” appears to us the servile imitation of the style of a composition,—a practice attempted only by composers of inferior rank, lacking in self-respect and dignity, as well as in originality of thought. We remember, to cite an example, hearing a piece for the piano not long ago that turned out to be, in conception, phrasing, harmonization, and what not, a slavish counterfeit of Schumann’s lovely “Blumenstück”; and yet, how far it fell short of its graceful prototype!

Such an attempt is, to our feeling, the worst type of plagiarizing. It reminds us forcibly of the sarcastic lines from Schiller’s “Wallenstein,” addressed by the chasseur to the cavalry sergeant, whom the former charges with aping the great general:

“How he hawks and spits, indeed, I may say,

You’ve copied and caught in the cleverest way.

But his spirit, his genius—oh, these, I ween,

On your dress-parade are but seldom seen.”

Of course, we should not be supposed to include in our condemnation such isolated cases as that of Schumann’s “Carnaval,” in which one number is a deliberate imitation of the style of Chopin—intended, however, as a graceful compliment to the great Pole.

To sum up: Let us not judge too severely what over- zealous critics are pleased to call plagiarisms. Let us bear in mind that, as all human productions are necessarily imperfect to a greater or lesser degree, perfect originality in musical ideas is a thing next to impossible, owing to the constitution and development of the human mind.

While we would condone a plagiarism that attests the presence of an abundant fund of musical ideas pouring in nolens volens upon a composer from his stored-up reminiscences; while we feel disposed to pardon him for the use of a theme or phrase not strictly original with him, provided he show, by the general treatment, that he could have created a substitute for the former if he so wished; the interest of music as a fine art demands, on the other hand, that we condemn and unmask him who tries to shine with a false luster on account of the utter absence of any light of his own.