Helpful Inquiries Answered by a Famous Authority Conducted by LOUIS C. ELSON, Professor of Theory at the New England Conservatory

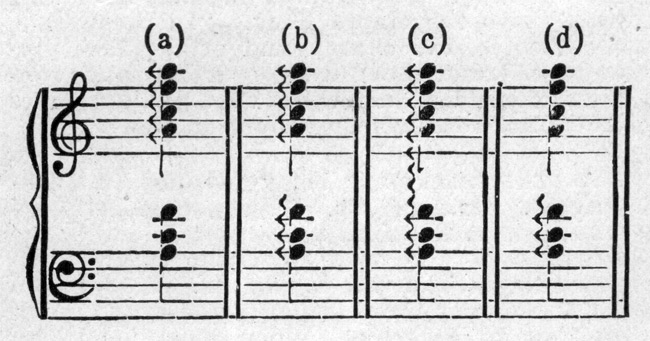

Q. Is there any rule governing the performance of arpeggios? I notice that some in playing arpeggios start both hands at the same time, while others play the left hand first and then the right hand immediately afterward. Please state how the following are to be played. Is b the same as c?— M. A. B.

A. If those are correctly notated (they often are not) the first arpeggio is to start its lowest note simultaneously with the chord of the left hand. In the second start the arpeggio in both hands simultaneously. In the third begin the arpeggio with the lowest note of the left hand and sweep gradually to the highest note of the right hand. In the last example begin the arpeggio with the lowest note of the left hand simultaneously with the full chord in the right hand. Rut I must warn you that there is a great deal of false notation in this matter, and you had better judge each case by its good or bad effect, independently of the notation.

Q. When composers write a melody to the song do they try to have the melody follow the inflexion of the voice or is this ignored? I often find songs by well known masters in which the words follow a melody which gives them a very different inflexion than that when the words are spoken.—Sister II.

A. You touch here upon a most important point in vocal composition. There are many cases where the composers defy the spoken, rhetorical accent. Sometimes it comes from ignorance, as when Handel accented the word “Chastisement” wrongly, through his lack of knowledge of English. The great masters strive to follow the spoken word in their musical accents. You will find plenty of good examples in Wagner, in Schumann, and in Hugo Wolf. Very often the rhetorical accents suffer terribly in translating a song from one language to another.

Q. What is the difference between a mezzo soprano and a soprano?—E.A.

A. In the salary (operatic) generally about forty per cent. But in the compass, again operatic, we find the mezzo-soprano going down to as low as G, and up to perhaps B-flat. The general lay of the tones (tessitura) of the mezzo-soprano would be in the lower register, while the soprano would sing easier in the higher register, even if not going any higher than a Mezzo. Such a role as Carmen, or Ortrud, or Mignon, would show the full compass of the mezzo-soprano. One might give the compass of a mezzo- soprano of first class as from G to B-flat. and of a good operatic soprano as from about B-flat or C to C or D. Thus while the compass does not display much difference the quality of tones and the position of the best tones would be different. The mezzo-soprano would generally be the heavier voice.

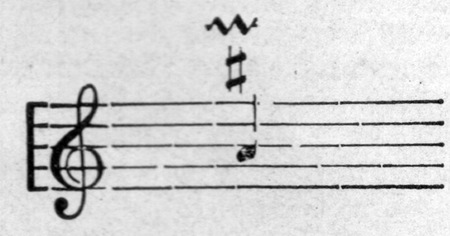

Q. Can you tell me how the following is played ? IT. S. K.

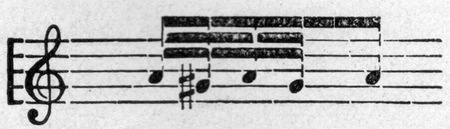

A. It is simply a double downward mordent. If the tempo is moderate or slow play it as follows:

But often this and the upward mordent stand for a short trill. There are innumerable instances of this sign in Bach meaning only a trill.

Q. How is “interpretation” defined by virtuoso pianists? Do they regard it as strict adherence to all marks of expression, etc., in the composition, or how they think they can best render it according to their own ideas so as to make it sound the best to their audiences?—A. J. V.

A. The best interpretation is that in which the player individualizes somewhat. In this sense Von Bülow was not of the really great pianists. He always played with the precision of a machine. In this connection I may quote a remark to me by Sir Hubert Herkomer. “When a pianist can always give the same result,” he said, “he ceases to be an artist and becomes a manufacturer.” I can recall Rubinstein playing the Moonlight Sonata at least half-a-dozen times, yet he never played it twice alike,—it was sometimes full moon and sometimes not. Mendelssohn used to become irritated when anyone criticised him for departing from the metronome marks upon some orchestral work. He held that the conductor should allow his own feeling to rule. The very word “interpretation” signifies that the artist is translating something according to his own thought, that he is giving his own view of the composition. Perhaps an anecdote of Chopin may illustrate this point. When Georges Sand (Mme. Dudevant) would beg him to play at her salon, after he had declined, as not feeling in the mood, he would sit down at the piano and would play through a piece in strict time, with all the precision of a music-box. The cultured audience would sometimes burst out laughing at the unexpected effect produced. I have heard De Pachmann do the same thing once or twice in public. Decidedly the artist must not be the slave of the expression-marks, but must rule them.

Q. What is the difference between a transcription and a variation?—C. O.

A. See my answer to “C. B. S.,” regarding “Agréments” and “Doubles.” A variation is, as its name implies, a repetition of a melody in a new dress. Yet there is something more to be said about variations. In the 17th and 18th centuries the variation kept the theme of the same length, the same modulations, and often, in the same tempo. But with Beethoven sometimes the variation became almost a metamorphosis of the theme. Examine the theme and variations of Beethoven’s Sonata for Piano, Op. 14, No. 2, the Andante movement, and you will find each variation repeating the theme so precisely, as to length, tempo and modulations, that any amateur can instantly recognize it in each of its disguises. Now take the variations at the end of the third symphony, or the slow movement of the fifth symphony. In the latter you will sometimes find the theme reproduced with exactly the same proportions, but at other times you will find the figures of the theme spun out into something almost entirely new, by means of development. Brahms’ variations are almost all of this latter type, which allows considerable freedom. With such variations there is danger that the skill of the composer may lead him to too great lengths. Both Brahms and Beethoven sometimes fell into this trap and went on and on until they had squeezed the very last drop out of their melodic lemon.

There used to be a ghastly style of variations (?) published in America, in which the composer (??) would give a few notes of the melody and then make a wild scramble up and down the keyboard on the tonic sub- dominant or dominant chord, splintered into meaningless arpeggios. These were not variations at all, and the scramble aforesaid had no more to do with the Silvery Wave or Home Sweet Home melody than the gymnastics would have if an orator put in a hop at every comma, a skip at every colon and a somersault at every period in his speech.

A transcription is the presentation of a musical composition in some other scoring than it was composed for. Thus if I play Annie Laurie upon piano it is a transcription. If I play Raff’s Cavatina, composed for violin, upon the horn, it is a transcription, etc.

Admirer, F. C. L., Etude Friend. M. T. S., Teacher in Milwaukee, and many others who have failed to give their complete names and addresses, are reminded that no questions are ever answered in this column unless this information accompanies the question.