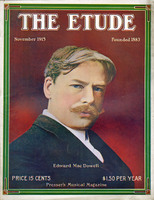

AN ESSAY By EDWARD MacDOWELL

[Editor's Note.—The excellent essay upon this page is from the volume known as "Critical and Historical Essays,' published by Arthur P. Schmidt. These discussions of various phases of musical education, history, science and æsthetics are twenty-one in number and embrace the more important lectures delivered by Mr. MacDowell when he was professor at Columbia University. After his death his literary work in this connection was collected and edited by Mr. W. J. Baltzell. Those who desire to become familiar with Mr. MacDowell's intellectual breadth and comprehensive scholarship will find these essays very enlightening indeed. "Suggestion in Music" is reproduced here through the courtesy of the publisher.]

IN speaking of the power of suggestion in music I wish at the outset to make certain reservations. In the first place I speak for myself, and what I have to present is merely an expression of my personal opinion; if in any way these should incite to further investigation or discussion, my object will in part have been attained.

IN speaking of the power of suggestion in music I wish at the outset to make certain reservations. In the first place I speak for myself, and what I have to present is merely an expression of my personal opinion; if in any way these should incite to further investigation or discussion, my object will in part have been attained.

In the second place, in speaking of this art, one is seriously hampered by a certain difficulty in making oneself understood. To hear and to enjoy music seems sufficient to many persons, and an investigation as to the causes of this enjoyment seems to them superfluous. And yet, unless the public comes into closer touch with the tone poet than that objective state which accepts with the ears what is intended for the spirit, which hears the sounds and is deaf to their import, unless the public can separate the physical pleasure of music from its ideal significance, our art, in my opinion, cannot stand on a sound basis.

The first step toward an appreciation of music should be taken in our preparatory schools. Were young people taught to distinguish between tones as between colors, to recognize rhythmic values, and were they taught so to use their voices as to temper the nasal tones of speech, in after life they would be better able to appreciate and cherish an art of which mere pleasure-giving sounds are but a very small part.

Much of the lack of independence of opinion about music arises from want of familiarity with its material. Thus, after dinner, our forefathers were accustomed to sing catches which were entirely destitute of anything approaching music.

Music contains certain elements which affect the nerves of the mind and body, and thus possesses the power of direct appeal to the public—a power to a great extent denied to the other arts. This sensuous influence over the hearer is often mistaken for the aim and end of all music. With this in mind, one may forgive the rather puzzling remarks so often met with; for instance, those of a certain English bishop that "Music did not affect him either intellectually or emotionally, only pleasurably," adding, "Every art should keep within its own realm; and that of music was concerned with pleasing combinations of sound." In declaring that the sensation of hearing music was pleasant to him, and that to produce that sensation was the entire mission of music, the Bishop placed our art on a level with good things to eat and drink. Many colleges and universities of this land consider music as a kind of boutonnière.

This estimate of music is, I believe, unfortunately a very general one, and yet, low as it is, there is a possibility of building on such a foundation. Could such persons be made to recognize the existence of decidedly unpleasant music, it would be the first step toward a proper appreciation of the art and its various phases.

Mere beauty of sound is, in itself, purely sensuous. It is the Chinese conception of music that the texture of a sound is to be valued; the long, trembling tone- tint of a bronze gong, or the high, thin streams of sound from the pipes are enjoyed for their ear-filling qualities. In the Analects of Confucius and the writings of Mencius there is much mention of music, and "harmony of sound that shall fill the ears" is insisted upon. The Master said, "When the music maker Che first entered on his office, the finish with the Kwan Ts'eu was magnificent. How it filled the ears!" Père Amiot says, "Music must fill the ears to penetrate the soul." Referring to the playing of some pieces by Couperin on a spinet, he says that Chinese hearers thought these pieces barbarous; the movement was too rapid, and did not allow sufficient time for them to enjoy each tone by itself. Now this is color without form, or sound without music. For it to become music, it must possess some quality which will remove it from the purely sensuous. To my mind, it is in the power of suggestion that the vital spark of music lies.

Before speaking of this, however, I wish to touch upon two things: first, on what is called the science of music; and secondly, on one of the sensuous elements of music which enters into and encroaches upon all suggestion.

If one were called upon to define what is called the intellectual side of music, he would probably speak of "form," contrapuntal design, and the like. Let us take up the matter of form. If by the word "form" our theorists meant the most poignant expression of poetic thought in music, if they meant by this word the art of arranging musical sounds into the most telling presentation of a musical idea, I should have nothing to say: for if this were admitted instead of the recognized forms of modern theorists for the proper utterance, we should possess a study of the power of musical sounds which might truly justify the title of musical intellectuality. As it is, the word "form" stands for what have been called "stoutly built periods," "subsidiary themes," and the like, a happy combination of which in certain prescribed keys was supposed to constitute good form. Such a device, originally based upon the necessities and fashions of the dance, and changing from time to time, is surely not worthy of the strange worship it has received. A form of so doubtful an identity that the first movement of a certain Beethoven sonata can be dubbed by one authority "sonata-form," and by another "free fantasia," certainly cannot lay claim to serious intellectual value.

Form should be a synonym for coherence. No idea, whether great or small, can find utterance without form, but that form will be inherent to the idea, and there will be as many forms as there are adequately expressed ideas. In the musical idea, per se analysis will reveal form.

The term "contrapuntal development" is to most tone poets of the present day a synonym for the device of giving expression to a musically poetic idea. Per se, counterpoint is a puerile juggling with themes, which may be likened to high- school mathematics. Certainly the entire web and woof of this "science," as it is called, never sprang from the necessities of poetic musical utterance. The entire pre-Palestrina literature of music is a conclusive testimony as to the non-poetic and even uneuphonious character of the inventions.

In my opinion, Johann Sebastian Bach, one of the world's mightiest tone poets, accomplished his mission, not by means of the contrapuntal fashion of his age, but in spite of it. The laws of canon and fugue are based upon as prosaic a foundation as those of the rondo and sonata form; I find it impossible to imagine their ever having been a spur on an incentive to poetic musical speech. Neither pure tonal beauty, so-called "form," nor what is termed the intellectual side of music (the art of counterpoint, canon and fugue), constitutes a really vital factor in music. This narrows our analysis down to two things, namely, the physical effect of musical sound and suggestion.

The simplest manifestations of the purely sensuous effect of sound are to be found in the savage's delight in noise. In the more civilized state, this becomes the sensation of mere pleasure in hearing pleasing sounds. It enters into folk song in the form of the "Scotch snap," which is first cousin to the Swiss jodel, and is undoubtedly the origin of the skips of the augmented and (to a lesser degree) diminished intervals to be found in the music of many nations. It consists of the trick of alternating chest tones with falsetto. It is a kind of quirk in the voice which pleases children and primitive folk alike, a simple thing which has puzzled folklorists the world over.

The other sensuous influence of sound is one of the most powerful elements of music, and all musical utterance is involved with and inseparable from it. It consists of repetition, recurrence, periodicity.

Now this repetition may be one of rhythm, tone tint, texture, or color, a repetition of figure or of pitch. We know that savages, in their incantation ceremonies keep up a continuous drum beating or chant which, gradually increasing in violence, drives the hearers into such a state of frenzy that physical pain seems no longer to exist for them.

The value of the recurring rhythms and phrases of the march is well recognized in the army. A body of men will instinctively move in cadence with such music. The ever recurring lilt of a waltz rhythm will set the feet moving unconsciously, and as the energy of the repetition increases and decreases, so will the involuntary accompanying physical sympathy increase or decrease.

Berlioz jokingly tells a story of a ballet dancer who objected to the high pitch in which the orchestra played, and insisted that the music be transposed to a lower key. Cradle songs are fashioned on the same principle.

This sensuous sympathy with recurring sounds, rhythm, and pitch has something in common with hypnotism, and leads up to what I have called suggestion in music.

This same element in a modified form is made use of in poetry, for instance, in Poe's "Raven,"

Quoth the raven, nevermore,

and the repetition of color in the same author's "Scarlet Death." It is the mainspring (I will not call it the vital spark) of many so-called popular songs, the recipe for which is exceedingly simple. A strongly marked rhythmic figure is selected, and incessantly repeated until the hearer's body beats time to it. The well-known tunes "There'll Be a Hot Time," etc., and "Ta-ra-ra, Boom-de-ay" are good examples of this kind of music.

There are two kinds of suggestion in music: one has been called tone-painting, the other almost evades analysis.

The term tone-painting is somewhat unsatisfactory, and reminds one of the French critic who spoke of a poem as "beautiful painted music." I believe that music can suggest forcibly certain things and ideas as well as vague emotions encased in the so-called "form" and "science" of music.

If we wish to begin with the most primitive form of suggestion in music, we shall find it in the direct imitation of sounds in nature. We remember that Helmholtz, Hanslick, and their followers denied to music the power to suggest things in nature; but it was somewhat grudgingly admitted that music might express the emotions caused by them. In the face of this, to quote a well-known instance, we have the "Pastoral" symphony of Beethoven, with the thrush, cuckoo, and thunderstorm. The birds and the storm are very plainly indicated; but it is not possible for the music to be an expression of the emotions caused by them, for the very simple reason that no emotions are caused by the cuckoo and thrush, and those caused by thunderstorms range all the way from depression and fear to exhilaration, according to the personality of individuals.

That music may imitate any rhythmic sounds or melodic figure occurring in nature, hardly needs affirmation. Such devices may be accepted almost as quotations, and not be further considered here. The songs of birds, the sound made by galloping horses' feet, the moaning of the wind, etc., are all things which are part and parcel of the musical vocabulary, intelligible alike to people of every nationality. I need hardly say that increasing intensity of sound will suggest vehemence, approach, and its visual synonym, growth, as well as that decreasing intensity will suggest withdrawal, dwindling, and placidity.

The suggestion brought about by pattern is very familiar. It was one of the first signs of the breaking away from the conventional trammels of the contrapuntal style of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The first madrigal of Thomas Weelkes (1590) begins with the words, "Sit down," and the musical pattern falls a fifth. The suggestion was crude, but it was caused by the same impulse as that which supplied the material for Wagner's "Waldweben," Mendelssohn's "Lovely Melusina," and a host of other works.

The fact that the pattern of a musical phrase can suggest kinds of motion may seem strange; but could we, for example, imagine a spinning song with broken arpeggios? Should we see a spear thrown or an arrow shot on the stage and hear the orchestra playing a phrase of an undulating pattern, we should at once realize the contradiction. Mendelssohn, Schumann, Wagner, Liszt, and practically everyone who has written a spinning song, has used the same pattern to suggest the turning of a wheel. That such widely different men as Wagner and Mendelssohn should both have adopted the same pattern to suggest undulating waves is not a mere chance, but clearly shows the potency of the suggestion.

The suggestion conveyed by means of pitch is one of the strongest in music. Vibrations increasing beyond two hundred and fifty trillions a second become luminous. It is a curious coincidence that our highest vibrating musical sounds bring with them a well-defined suggestion of light, and that as the pitch is lowered we get the impression of ever increasing obscurity. To illustrate this, I have but to refer you to the Prelude to "Lohengrin." Had we no inkling as to its meaning, we should still receive the suggestion of glittering shapes in the blue ether.

Let us take the opening of the "Im Walde" symphony by Raff as an example; deep shadow is unmistakably suggested. Herbert Spencer's theory of the influence of emotion on pitch is well known and needs no confirmation. This properly comes under the subject of musical speech, a matter not to be considered here. Suffice it to say that the upward tendency of a musical phrase can suggest exaltation, and that a downward trend may suggest depression, the intensity of which will depend upon the intervals used. As an instance we may quote the "Faust" overture of Wagner, in which the pitch is used emotionally as well as descriptively. If the meaning I have found in this phrase seems to you far-fetched, we have but to give a higher pitch to the motive to render the idea absolutely impossible.

The suggestion offered by movement is very obvious, for music admittedly may be stately, deliberate, hasty, or furious, it may march or dance, it may be grave or flippant.

Last of all I wish to speak of the suggestion conveyed by means of tone-tint, the blending of timbre and pitch. It is essentially a modern element in music, and in our delight in this marvellous and potent aid to expression we have carried it to a point of development at which it threatens to dethrone what has hitherto been our musical speech, melody, in favor of what corresponds to the shadow languages of speech, namely, gesture and facial expression. Just as these shadow languages of speech may distort or even absolutely reverse the meaning of the spoken word, so can tone color and harmony change the meaning of a musical phrase. This is at once the glory and the danger of our modern music. Overwhelmed by the new-found powers of suggestion in tonal tint and the riot of hitherto undreamed of orchestral combinations, we are forgetting that permanence in music depends upon melodic speech.

In my opinion, it is the line, not the color, that will last. That harmony is a potent factor in suggestion may be seen from the fact that Cornelius was able to write an entire song pitched upon one tone, the accompaniment being so varied in its harmonies that the listener is deceived into attributing to that one tone many shades of emotion.

In all modern music this element is one of the most important. If we refer again to the "Faust" overture of Wagner, we will perceive that although the melodic trend and the pitch of the phrase carry their suggestion, the roll of the drum which accompanies it throws a sinister veil over the phrase, making it impressive in the extreme.

The seed from which our modern wealth of harmony and tone color sprang was the perfect major triad. The raison d'étre and development of this combination of tones belong to the history of music. Suffice it to say, that for some psychological reason this chord (with also its minor form) has still the same significance that it had for the monks of the Middle Ages. It is perfect. Every complete phrase must end with it. The attempts made to emancipate music from the tyranny of this combination of sounds have been in vain, showing that the suggestion of finality and repose contained in it is irrefutable.

Now if we depart from this chord a sensation of unrest is occasioned which can only subside by a progression to another triad or a return to the first. With the development of our modern system of tonality we have come to think tonally; and a chord lying outside of the key in which a musical thought is conceived will carry with it a sense of confusion or mystery that our modern art of harmony and tone color has made its own. Thus, while any simple low chords accompanying the first notes of Raff's "Im Walde" symphony, given by the horns and violins, would suggest gloom pierced by the gleams of light, the remoteness of the chords to the tonality of C major gives a suggestion of mystery; but as the harmony approaches the triad the mystery dissolves, letting in the gleam of sunlight suggested by the horn.

Goldmark's overture to "Sakuntala" owes its subtle suggestion to much the same cause. Weber made use of it in his "Freischütz," Wagner in his "Tarnhelm" motive, Mendelssohn in his "Midsummer Night's Dream," Tchaikovsky in the opening of one of his symphonies.

Modern Exaggeration

In becoming common property, so to speak, this important element of musical utterance has been dragged through the mud; and modern composers, in their efforts to raise it above the commonplace, have gone to the very edge of what is physically bearable in the use of tone color and combination. While this is but natural, owing to the appropriation of some of the most poetic and suggestive tone colors for ignoble dance tunes and doggerel, it is to my mind a pity, for it is elevating what should be a means of adding power and intensity to musical speech to the importance of musical speech itself. Possibly Strauss's "Thus Spake Zarathustra" may be considered the apotheosis of this power of suggestion in tonal color, and in it I believe we can see the tendency I allude to. This work stuns by its glorious magnificence of tonal texture; the suggestion, in the opening measures, of the rising sun is a mighty example of the overwhelming power of tone color. The upward sweep of the music to the highest regions of light has much of splendor about it; and yet I remember once hearing in London, sung in the street at night, a song that seemed to me to contain a truer germ of music.

For want of a better word I will call it ideal suggestion. It has to do with actual musical speech, and is difficult to define., The possession of it makes a man a poet. If we look for analogy, I may quote from Browning and Shakespeare.

Dearest, three months ago

When the mesmerizer, Snow,

With his hand's first sweep

Put the earth to sleep.

—Browning, A Lovers' Quarrel

Daffodils,

That come before the swallow dares, and takes

The winds of March with beauty; Violets dim,

But sweeter than the lids of Juno's eyes.

—Shakespeare, Winter's Tale.

For me this defies analysis, and so it is with some things in music, the charm of which cannot be ascribed to physical or mental suggestion, and certainly not to any device of counterpoint or form, in the musical acceptance of the word.— (Copyright 1912, by Arthur P. Schmidt.)