[If the musical people of America had the clarity of vision possessed by Mr. Edward Baxter Perry, the following article would not be necessary. Although blind, Mr. Perry has seen many things which those of us blessed with sight often ignore. During several decades of concertizing Mr. Perry has given some three thousand recitals. Visiting every State repeatedly, he has made himself thoroughly familiar with all musical conditions. The average man looks upon a journey of a few hundred miles with apprehension, but here is a man whose artistic tours have taken him over a hundred thousand miles and he is sightless. Surely the judgment of such a man of accomplishment is worthy of attention.

Mr. Perry, although he has never professed to be a teacher, has come in contact with teachers all his life, from Liszt, Clara Schumann and Kullak to unknown instructors in rural communities. He knows what noxious swindles have often come from iron-clad proprietory methods. He has watched promotors of special methods circle their schemes with contracts forcing the teacher to use one method and one only. He has seen others employ every political device to make certain methods obligatory through State or association legislation. He has seen publishers endeavor to foist their wares upon the music teachers by tricks that would make a slum politician hold his nose. If there was one supremely good method the highly organized Teuton nations would long ago have seen the desirability of adopting that one method and discarding all others. Austria would have a Koenigliche und Kaiserliche Officialles Leschitizky Methode or a Staatliche Liszt Methode or a Sauer Methode or a Busoni Methode. Anyone who taught anything else would have to pay a strafe of many marks or kroners. Put the Gorman nations with their high academic efficiency know that to make proprietory systems obligatory would be to play the funeral march of the art of music. In German cities where local conditions tended to become arbitrary, as indeed they were in Leipsic during the days of Moscheles and in Stuttgart during the days of Lebert and Stark, artistic progress was always threatened and impeded. In time these institutions began to retrograde until a new impetus was given by a more eclectic administration.

Therefore The Etude stands unequivocally against all attempts to intimidate the teachers by employing State or organization legislation making the use of any proprietory method compulsory. Think how monstrous would be conditions compelling an individual to engage none but a physician who was a homeopath or an allopath or a naturopath or a mental heeler or worse yet, a doctor of proprietory remedies or patent medicines.-—The Editor of The Etude.]

In these days nearly every home, however modest, contains a piano and one or more piano students. The pupils themselves may or may not be interested and ambitious, but the fond mothers are in all cases anxious for their children's progress and are searching eagerly for the teachers who can produce the best results in the shortest time and for the least money.

It is only natural that music teachers, realizing this demand and feeling the pressing need of an income, are in so many cases substituting business policy for conscience and are urging their special claims to confidence and patronage, on the ground that they have a peculiar and vastly superior method of teaching and playing the piano, not possessed by their competitors and certain to produce better players in less time than any other.

The monumental ignorance and infantile credulity of the American public in the past have made us the victims of many impostures, so that the temptation to teachers to attempt something of the sort is well-nigh irresistible. Many there be who yield to it and verily they are not without their reward in hard cash.

For example, I have a friend in a leading western city, a modest, intelligent, well-equipped musician, who some years ago was struggling for existence, doing good work with a very small class and always on the verge of starvation. Next door to him was a charlatan who advertised in large letters: "Singing Taught on the Breath." This is not a joke but a fact. His studio was crowded and his automobile of the latest model.

Finally in desperation my friend looked in his Greek dictionary for two words meaning respectively sensible

and eclectic, combined them into a term never heard on sea or land and advertised that as his method. His class began to grow at once and is increasing steadily, although he continues to teach legitimately, exactly as he did from the first.

The more incomprehensible and unpronounceable the name attached to any method, the more it impresses the general public. One is reminded of the good old darky woman, who when asked what passage in her dear and well-worn Bible she liked best, replied: "I can't jess say, sah, but I certainly does get a power of comfort out of that blessed word Mesopotamia."

Let me say an earnest sincere word of warning to all ambitious music students and to all solicitous parents. Beware of all "methods" and especially of all rabid methodism among teachers. They are always misleading and pernicious. Such teachers are either humbugs or deluded, half-posted, one-sided fanatics.

There absolutely is no such thing as a one and only method of teaching either voice or piano, any more than there is one universal, infallible "cure-all" patent medicine, though many are advertised. This simple fact seems too obvious to need stating, yet it is ignored on all sides. I speak from fifty years of experience as student, teacher and concert pianist.

There are certain general fundamental principles which every good musician knows and uses. The rest depends on the intelligence and discrimination of the teacher in applying these principles to individual needs and on the faithfulness and adaptability of the pupil in assimilating and utilizing them.

Masters Without Methods

There is no special method of cooking or of teaching mathematics. Why should there be in music? Liszt had no "method," yet it will be conceded that he played fairly well. I have never heard his equal before or since.

Theodore Kullak had no method, though he was the leading teacher of his generation. I was with him for three years in Berlin and once asked him, as I wished to answer intelligently the many questions addressed to me. He replied indignantly, "Tell the fools we are not studying a method, we are studying the piano- forte?"

Madame Schumann had no method. I was with her a year, and though she was technically grounded by her father, Professor Wieck, she was most eclectic in her teaching.

Leschetizky has no method, though what is called such has been the fad in America for many years. I have read a letter from him emphatically stating this and expressing the wish that the dear public would finally come to believe him, as he was tired of reiterating the fact. He is simply one of the great artist- teachers of the world. Incidentally I will say that no two of his supposed representatives teach alike. Each of them has some special phase of technical training which was needed in his or her stage of development and advertises that as the "Leschetizky" method.

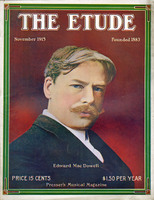

Since the deplorable death of MacDowell we have heard a great deal about the "MacDowell method." Now I have heard MacDowell give an entire concert program, mostly of his own compositions, and there was no evidence of any special method about his playing, other than is used by concert pianists on both sides of the water. Moreover, I happen to know three of

MacDowell's very enthusiastic pupils. One is a stiff, conservative, rather uninteresting, although accurate, player and a very good teacher. The second is a free, emotional player, giving the impression of an amateur of unusual musical talent and taste, rather than a professional of any particular school. The third is a woman younger than either of the other two, who plays like a man of considerable concert experience. No one who heard the three play in succession would ever imagine them pupils of the same teacher or examples of the same method.

After all, the use of the word method in connection with music is an absurdity. Every composition differs from every other, requires different tone coloring and shading. To attempt to apply the same touch or method or position and use of the hands at all times would be as ridiculous as to attempt to paint all pictures with the same color.

Imagine advertising to Teach Painting on the Blue or How to Write Poetry on the Verb. Fancy anyone being impressed and deluded by such impostures. Yet in music their name is legion. Music is not a bit of jugglery to be performed only when one knows the special tricks. It is not a mystery to be solved by means of secret formulae, of which a few hold the monopoly. It is simply an art like any other, existing for the purpose of expressing human thought, fancy or emotion, by means of its own peculiar medium, which is tone. Its manifold variations, shadings and combinations are as numerous as the colors on the painter's palette. Successful use comes only by slow development, through long patient years of study, and training of brain and heart, as well as of voice or hand. There are no short cuts, no patent methods.

The vital practical question underlying this whole subject for parents and music students is, of course, How can I be sure of securing the right and proper teacher? To this question there can be but one answer. Look at the results accomplished by any given teacher and be guided by them. It is results that count.

Parents who are not themselves musicians are usually the most anxious that their children should become so, should enjoy the advantages which they themselves have missed all their lives. Unfortunately they are the most incompetent of all persons to judge of the relative merits of teachers, since they have no experience or professional knowledge of their own. To these I say, choose the teacher who has turned out a large percentage of good singers or players and you can hardly go wrong.

An Unfair Judgment

It is often unfair to judge of the value of a musician as instructor by his own performances, particularly if such teacher is busy and well-established. No pianist, for instance, could possibly teach six or seven hours a day six days in the week and practice sufficiently so that his own playing would do him justice. The result with pupils is a much fairer test.

Of course, there are music students so wholly devoid of capacity that the combined efforts of a dozen good teachers never could make of them even passable performers. But, on the other hand, no good teacher could have a considerable class for a number of years without producing some acknowledged fine musicians.

Never mind how much some special method may be advertised and advocated, or what wonderful digital performances may be done on the table or on any mechanical appliances, feats which perhaps Paderewski himself could not copy. If a musician has taught even a moderately large class for half a dozen years in any town or city and has produced no fine players or singers, generally recognized as such, that is not the teacher you want.

The object of training the voice is to learn to sing and the object of studying the piano is to play the piano.