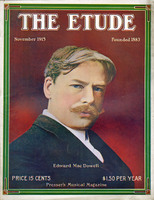

Several of the following excerpts appeared in past issues of The Etude. When coming from outside sources full credit has been given. They are assembled here for the convenience of many Etude readers desiring a fuller knowledge of MacDowell’s accomplishments.

In The Outlook for December 22, 1906, Henry T. Finck, writing on “Edward MacDowell, Musician and Composer,” also had something to say on Edward MacDowell the man. At all events, he recounts some sayings and incidents which are treasure-trove to those who love the most noted American composer. “To his friends,” writes Mr. Finck, “his droll and truly American gift of humor has always seemed one of his most charming traits. In a letter to me he once referred to his student days at the Paris Conservatoire. Life in Paris seemed to him ‘a huge but rather ghastly joke.’ His fellow-students ‘never seemed to miss the absence of the word “home” in their language. Most of them looked as if they had been up ever since they were born. They seemed to live on cigarettes, odd carafons of wine, and an occasional shave.’

“The ‘occasional shave’ is delightfully characteristic of MacDowell’s wit. In his conversation he always kept the listener amused with such unexpected turns— as he does in his music. Scherzo is Italian for joke, and it is in his scherzo movements that we often hear him at his best. His famous teacher, the Venezuelan pianist, Teresa Carreño, hardly ever plays his second pianoforte concerto without being compelled to repeat the presto giocoso.

Another of his traits was revealed during his Conservatoire days. Though but fifteen years old, he soon discovered that it was not the right place for him. There was too much striving for effect for its own sake, and not sufficient reverence for the masters, to suit this American lad. Famous professors like Marmontel, Mathias and Ambroise Thomas did not hesitate to mutilate a composition or to insert measures of their own to make it what they deemed more effective. He packed his trunk and went to Stuttgart. Here there was no lack of reverence for genius, but there was what throughout his life he hated quite as much —pedantry; so, after six weeks, he moved on again, a real American, in quest of the best wherever it may be found, and bound to find it.

“He found it at last in Frankfort, where there was a pianist, Carl Heymann, who ‘dared play the classics as if they had actually been written by men with blood in their veins.’ Under his fingers ‘a sonata was a poem.’ The eminent composer, Raff, was director of the Frankfort conservatory. By him MacDowell was confirmed in his tendency toward writing music with a pictorial or poetic background. The death of Raff revealed the emotional nature of the American youth. His first pupil, Miss Marian Nevins, who became his wife two years later, says regarding this tragic event:

” ‘He came to me at the hour for my lesson, looking so white and ill that I was frightened. His voice broke as he said only the words, ‘Raff is dead.’ There was a sweet hero-worship of a shy boy for an almost equally shy man, and for months after Raff’s death he was in a morbid condition. He gave me eighteen marks—all he had at the time—and said, ‘as I knew more about flowers than he did, would I get him some roses to send?’ So I bought a mass of roses and, what was unusual in Germany, had them sent not even bound together, and these were put about Raff, nearer than the grand, beautiful floral things sent by the dozen.’

“Like all students of the pianoforte, MacDowell always adored the personality and the works of Liszt, to whom his first concerto is dedicated. Following the advice of Raff, he had visited Weimar, where he was greatly encouraged by the cordial praise Liszt bestowed both on his playing and his compositions, and by the invitation to play his first piano suite at the next convention of the Allgemeine Musik-Verein, over which Liszt presided. There was, to be sure, more honor than profit in this. A man cannot live on compliments and applause, and MacDowell, like most other musicians, found it extremely hard to make a living in Germany unless he used up all his vitality in teaching, leaving none for creative work. Luckily, his wife had a little money, so they took the daring risk of dropping everything but composition and settling down to a quiet life in and near Wiesbaden. It was here that MacDowell wrote the compositions from opus 23 to opus 35.

“Those were idyllic days. ‘The one dark spot,’ Mrs. MacDowell writes, ‘was a long and severe illness of mine brought on by over-anxiety and trying to do work which I was not well used to; but in spite of it all, we were very happy. The six Idylls, op. 28, of which I am very fond, I associate with our little flat in the Jahnstrasse. I had been ill a long time, and felt Edward was neglecting his work in his care of me. So I made him promise he would write a daily sketch for a week and these six were the result of this promise. I in bed and he writing music in the next room! Of course, he changed and “fixed” them later on, but the actual music was written in those six days.’

“Those were idyllic days. ‘The one dark spot,’ Mrs. MacDowell writes, ‘was a long and severe illness of mine brought on by over-anxiety and trying to do work which I was not well used to; but in spite of it all, we were very happy. The six Idylls, op. 28, of which I am very fond, I associate with our little flat in the Jahnstrasse. I had been ill a long time, and felt Edward was neglecting his work in his care of me. So I made him promise he would write a daily sketch for a week and these six were the result of this promise. I in bed and he writing music in the next room! Of course, he changed and “fixed” them later on, but the actual music was written in those six days.’“After nearly four years of Wiesbaden it became imperative to replenish the exchequer, and an attempt was made to secure a position as local examiner for the London Royal Academy of Music. MacDowell had been specially recommended for this position, and the matter finally rested in the hands of Lady Macfarren. She was a nice old lady, and things seemed certain until she suddenly said: ‘I hope you have no leaning toward the school of that wild man, Liszt.’ The American had to confess sorrowfully that he had, and when he got home he found a note saying that the place was not suited for him! It was not the first time, and far from the last, that devotion to an ideal cost him a worldly advantage.”

MacDowell During His Last Illness

Mary Mears in “The Craftsman,” July 1909.

It was on a beautiful morning in May, 1906, that I first saw MacDowell. I had accompanied my sister, who was making a bas-relief portrait of him at the time, to his home. The room which we entered was flooded with sunlight. The tops of some trees in a nearby street, all covered with tender green leaves, could be seen through the windows. They danced constantly, seeming to tell of a happiness without end. And their message had entered that room! Never have I seen an apartment so essentially radiant! The musician sat there in his invalid chair, in his clothes of soft white flannel, childlike, wondering, very beautiful, with the naïve simplicity which had ever characterized him; while coming and going in and out of the apartment as her duties summoned her, was the musician’s devoted and heroic wife. She approached, and he turned toward her with a movement of which it is a profanation to speak, save that which is most beautiful is most ever open. He lifted to her eyes in which there was a steadfast, luminous trust such as I have never seen in any other human countenance.

Mrs. MacDowell directed our attention to a sketch of Liszt, which was hanging on the wall, and MacDowell seemed to recall making the drawing. He began to speak, a little hesitatingly, but not in the least incoherently. He told of the finding of water with a willow wand on his farm in Peterboro, New Hampshire —a favorite story; he told of a rattlesnake, which, when a burglar entered the house of its sleeping master, rattled for the police. A humorous gleam deepened the boyish blue of his eyes. But once in a while he looked in a puzzled way at the artist.

That the sitting might not fatigue him, a game of dominoes was begun, and the infinite sensitiveness with which he lifted and laid down the bits of ivory revealed the musician. One seeing him for the first time and unaware of his history, could not have doubted what he was.

As he sat there I fell to studying him. Surely long years of musical creativeness had added something to the modeling of the face, so that now, when the poor mind was bewildered and deranged, the suggestion of creative distinction did not vanish. It was the fact of the rare beauty and meaning of the face remaining intact, while into the eyes flashed at moments a fleeting perception that something had befallen him which he could not understand, it was this union of the outward form which retained its dignity, with the confusion of the inward forces, that made MacDowell, at this time, a most tragically symbolic figure. The whole problem of the soul and its struggle for attainment was there.”

MacDowell as a Listener

T. P. Currier in “The Musical Quarterly.”

The wear and tear of MacDowell’s high-strung organization was constantly going on. He could not hear music of any kind without listening with extreme intensity. One evening I inveigled him into going with me to a social gathering given in their rooms by a club of artists. Some one among others played a violin solo—not very well at that. A lady remarked to me afterwards, “Did you see MacDowell? The poor fellow couldn’t keep his head still during all that dreadful playing!”

It was largely due to this pull upon his nerves that he kept away from concerts as much as possible. At the Symphony concerts his had become a familiar figure in the second balcony of the old Music Hall. Curious people soon began to notice that frequently during the performances of “classics” he would disappear, to return when some modern number was to be played.

“What is the matter with MacDowell?” they said, “he can’t seem to stand a Beethoven symphony.” And, “Why doesn’t MacDowell go to concerts like the other fellows (referring to his brother composers)? The truth was that MacDowell knew the classics from A to Z and did not care to waste his strength on them. New and other modern works were more interesting and their scoring more important to him. To take in more than one such work of large dimensions was all he could possibly do without exhaustion. Therefore, he was actually compelled to save himself whenever possible.

MacDowell and the Classics

[Editor’s Note.—The following is an extract from an article appearing in the London Music Student from the pen of MacDowell’s friend, Templeton Strong, an American composer of European renown.]

“Of the classics MacDowell seldom spoke and, while imbued with all due respect and admiration for them, I imagine he felt their possible restrictive influences upon his modes of expression. He had a sincere admiration for Liszt’s compositions, especially the E flat piano concerto and three or four of his symphonic poems. Great, too, was his admiration for Chopin, although I do not think that the psychology of Chopin appealed to him as much as did that of Grieg. The ‘open-airness’ of Grieg’s work appealed to him very particularly, perhaps more than that of any other living composer, yet I believe he felt Grieg’s limitations. He was also partial to some of Tchaikovsky’s work, appreciating his melodic beauty and tenderness of expression. Of course, his admiration for his master, Joachim Raff, was very great, however he regretted the excessive output of (in a great measure) very mediocre piano music. Of Richard Wagner he knew very little (critics of MacDowell’s compositions of that period notwithstanding) and he often said that he was reserving the study of Wagner for a later day.

“Edward was at that time in the midst of the ‘Sturm und Drang’ period of his existence and it seems to me of interest to make known so far as I may the conditions of his musical mentality at this largely formative period, as having a certain bearing upon his ulterior development, for it was at this time I believe that the seed of his future work was being sown.

“All music that was sincere (preferably based upon a picturesque and poetic concept) and that sounded well at once aroused his interest. On the other hand, the purely academic dry as dust order of composition did not appeal to him at all—he failing to see its raison d’être, howsoever scientific it might be. A simple beautifully harmonized melody appealed to him infinitely more than a passably sounding and very erudite quadruple canon. Of the latter he would often have echoed the saying of Dr. Johnson (I think it was), who upon being told that the composition just performed by a young lady was extremely difficult, replied, ‘Madam, I would that it were impossible.’ “

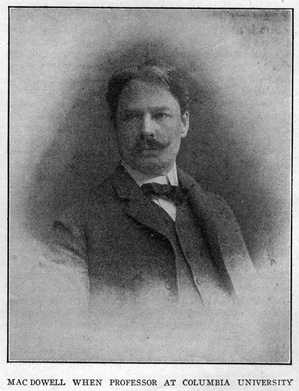

“Though I did no teaching myself until within the last eight years, I was in close touch with Mr. MacDowell’s own work. I saw many of his theories come into existence, some of them to last, others to be discarded; and, perhaps, my most vivid impression of the result of his experience with hundreds of students was his firm belief that no cut-and-dried method could be adopted in teaching the piano. That certain general rules and laws always remain more or less the same, but the fact that every individual possessed a hand curiously different from the rest of the world, seemed to demand a different so-called method for each person.

“However, almost as a contradiction to what I have said, Mr. MacDowell maintained that the stiff technical training he had had, first under Carreño, who was a fine teacher, though a young girl when she taught him; then the cruelly hard discipline at the Paris Conservatory, followed by two years’ work with Carl Heymann, whose short career was one of dazzling virtuosity, had been of inestimable value; but one must not forget that this was the training of a virtuoso, where practically unlimited time was given for the acquirement of pianistic technique. But different conditions confront the ordinary man or woman who has, perhaps, but two years in which to be helped in every direction musically, after perhaps years of plodding through endless studies.

“But, after all, the things that made Edward MacDowell a great teacher was not methods or teachers. It was the infinite patience, the undivided interest and the untiring enthusiasm that he brought to each student. The one of, comparatively speaking, small talent was for the time being just as important as the most brilliant. This sometimes did harm—a student, not realizing that he was no exception to the general rule in this infinite care, assumed he must be of unusual talent, which led to disappointment. More often, however, there was a keen appreciation of the great opportunity presented.

“One may sum up this estimate of Edward MacDowell as a teacher: He was free from pedantic rules, yet thoroughly practical in working out individuality the problems confronted with each pupil. He gave of himself unsparingly, and there were few who studied with him who did not feel that music was only a part of what had been learned in their lessons with Edward MacDowell.”—From an article by Mrs. MacDowell in The Etude, November, 1914.

MacDowell’s Harmonic Methods

Lawrence Gilman in his biography “Edward MacDowell.”

“His method of harmonic manipulation is ingenious and pliable. An over-insistence upon certain formulas —eloquent and vital in themselves—has been charged against it, and the accusation is not entirely without foundation. MacDowell is exceedingly fond of the seventh and ninth chords, and of suspensions of the chord of the diminished seventh. There is scarcely a page throughout his latter work in which one does not encounter these effects in but slightly varied form. There is no doubt, however, that it is in his adroit and copious use of such combinations that one must ascribe the continual richness of his harmonic texture. I can think of no other composer save Wagner whose chord progressions are so opulently colored. His tonal web is always densely woven. He avoids thinness as he avoids the banal phrase and futile decoration. In addition to the pageantry of his chord combinations as such, his evident polyphonic tendency is responsible for much of the solidity of his tonal fabric. His pages, particularly in the more recent works, are studied with examples of felicitous and dextrous counterpoint— poetically significant and of the most elastic and untrammeled contrivance.

“Always he is the essential poet, the clairvoyant impressionist, sealing with life in its large and profound as well as its intimate aspects, limning tenderly, yet with a controlling and serene philosophy, such phases of the visible and human worlds as touch and quicken his imagination. His chief claim to perpetuity is, I think it will be found, that he has awakened in music that sense of the invisible, the hidden wonder and enchantment behind the manifest presence of the world, which it is the signal privilege of the Celtic imagination to discover and enforce. He has evoked the incalculable spell, has opened a door into a new and shining world. That, I believe, is what is essential and individual in his art—the disclosure of an immemorial magic in familiar things.”

“Unspoken words at parting, Find their voice in song.

Ah! Sing them soft and tenderly, The song will ne’er last long.

“And hand grasps hand at parting, Heart finds heart in song.

Unspoken love sing tenderly, ‘T will last as life is long

—From the copyrighted verses of Edward MacDowell.

From an interview secured by William Armstrong for The Etude (July, 1902).

“Language and music have nothing in common. In one way that which is melodious in music becomes doggerel in verse, and meter is hardly of value. Sonnets in music become abominable. I have made many experiments for finding the affinity of language and music. The two things are diametrically opposed, unless music is free to distort syllables. A poem may be only four words and yet those words may contain enough suggestion for four pages of music; but to found a song on those four words would be impossible. For this reason the paramount value of the poem is that of its suggestion in the field of instrumental music where a single line may be elaborated upon. The value of poetry is what it makes you think. A short poem would take a lifetime to express; to do it in as many measures is impossible. The words clash with the music, they fail to carry the full suggestion of the poem. If the music stuck to the meter of the poem it would often be vulgar music. Verses that rhyme at the end of every phrase make poor settings to music. The main point is to hold closely to the ideal of the song—to sustain the balance of art. English presents great difficulties in the matter of accents, but the French none. In the choice of words for song settings Heine proves the most singable.”

Following is a list of MacDowell’s compositions, including those published under the nom de plume, Edgar Thorn. The dates in parenthesis are the years in which the pieces were issued:

Works With Opus Numbers.

Op. 9—Two old songs. (1894.)

Op. 10—First modern suite for pianoforte. (1883.)

Op. 11 and 12—Album of five songs. (1883.)

Op. 13—Prelude and fugue for pianoforte. (1883.)

Op. 14—Second modern suite for pianoforte. (1883.)

Op. 15—First concerto, in A minor, for pianoforte and orchestra. (1885.)

Op. 10—Serenata for pianoforte. (1883.)

Op. 17—Two fantastic pieces for concert use, for pianoforte. (1884.)

Op. 18—Barcarolle in F and humoreske in A, for pianoforte. (1884.)

Op. 19—Wald-Idyllen, for pianoforte. (1884.)

Op. 20—Three poems for pianoforte, four hands. (1885.)

Op. 21—Moon pictures, after H. C. Anderson, for pianoforte, four hands. (1885.)

Op. 22—Hamlet and Ophelia, two poems for orchestra. (1885.)

Op. 23—Second concerto inD minor, for pianoforte and orchestra. (1890.)

Op. 24—Four compositions for pianoforte. (1887.)

Op. 25—Lancelot and Elaine, symphonic poem for orchestra. (1S88.)

Op. 26—From an Old Garden, six songs. (1887.)

Op. 27—Three songs for male chorus. (1890.)

Op. 28—Six idyls, after Goethe, for pianoforte.

Op. 29—Lamia, third symphonic poem for orchestra. (1908.)

Op. 30—The Saracens and Lovely Alda, two fragments from the Song of Roland, for orchestra. (1890.)

Op. 31—Six poems, after Heine, far the pianoforte. (1887.)

Op. 32—Four little poems, for pianoforte. (1888.)

Op. 33—Three songs. (1894.)

Op. 34—Two songs. (1889.)

Op. 35—Romance, for violoncello, with orchestral accompaniment. (1888.)

Op. 36—Etude de concert, for pianoforte. (1889.)

Op. 37—Les Orientales, three pieces, for pianoforte. (1889.)

Op. 38—Marionettes, six little pieces, for the pianoforte. (1S88.)

Op. 39—Twelve studies for the pianoforte. (1889.)

Op. 40—Six love songs. (1889.)

Op. 41—Two songs for male chorus. (1889.)

Op. 42—Suite No. 1, for orchestra. (1891.)

Op. 43—Two Northern songs, for mixed chorus. (1891.)

Op. 44—Barcarolle, song, for mixed chorus. (1892.)

Op. 45—Sonata tragica (November 1), for pianoforte. (1893.)

Op. 46—Twelve virtuoso studies, for the pianoforte. (1894.)

Op. 47—Eight songs. (1893.)

Op. 48—Second (Indian) suite, for orchestra. (1897.)

Op. 49—Air and Rigaudon. (1894.)

Op. 50—Second sonata, Eroica, for pianoforte. (1895.)

Op. 51—Woodland Sketches, for pianoforte. (1890.)

Op. 52—Three choruses, for male voices. (1897.)

Op. 53—Two choruses, for male voices. (1898.)

Op. 54—Two choruses, for male voices. (1898.)

Op. 55—Sea Pieces, for pianoforte. (1898.)

Op. 56—Four songs. (1898.)

Op. 57—Third sonata, Norse, for pianoforte. (1900.)

Op. 58—Three songs. (1898.)

Op. 59—Fourth sonata, Keltic, for pianoforte. (1901.)

Op. 60—Three songs. (1902.)

Op. 61—Fireside Tales, for pianoforte. (1902.)

Op. 62—New England Idyls, for pianoforte. (1902.)

Works Without Opus Numbers.

Two songs from the Thirteenth Century, for male chorus. (1897.)

Six little pieces, after sketches by J. S. Bach, for pianoforte.

Technical exercises for the pianoforte (two books).

Columbia College songs.

Many transcriptions of old Clavecin music.

The following sets of pieces of MacDowell were published under the assumed name of Edgar Thorn:

In Lilting Rhythm (two pieces).

Forgotten Fairy Tales (four pieces).

Six Fancies (six pieces).

Amouret