The careers of Louis Moreau Gottschalk and Dr. William Mason have been discussed previously in this series and in connection with them is given some insight to the musical conditions in America which surrounded those notable figures in our history. The attention of the reader was drawn to the fact that while Dr. Mason was very clearly representative of the Americanism of New England, Gottschalk, with his French mother and his English father, was brought up in the Latin atmosphere of New Orleans and was far more a Latin-American composer than an American.

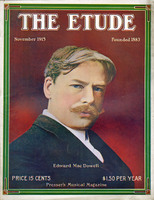

With MacDowell we have a new and distinctively different type. Mason and Gottschalk were both born in the year 1829. MacDowell was born thirty years later, and those three intervening decades were of the greatest significance to the music of the new world. Much of this was due to the splendid initiative of Theodore Thomas as well as to the activity of Dr. Mason. When MacDowell was a boy in New York, Thomas was organizing his Symphony Orchestra that was to do such magnificent pioneer work. The liberal attitude of the young conductor led him to introduce in America the works of many composers who found difficulty in getting a hearing in the hide-bound musical centres of Europe. Wagner was not the only one who owed a debt to Thomas for valuable propaganda. It is thus quite clear that a young man with musical inclinations in the New York City of a half a century ago had advantages which were not to be scorned.

MacDowell’s Ancestry and Youth

MacDowell’s nearest ancestral connection to the old world was to Ireland. His grandfather, Alexander MacDowell, and his grandmother, Sarah Thompson, were both born in Ireland. The name MacDowell is clearly of Scotch origin and it is for this reason that he is given the credit of being of Scotch-American blood. His mother, Frances M. Knapp, was an American lady whose ancestors have been traced to England. MacDowell’s grandfather came to America shortly after the beginning of the last century. The composer’s father was a successful New York business man. The noted American musician was born at 200 Clinton Street, New York, December 18, 1861. His birthplace, long since, fell under the swarm of the alien and industrial advance which has swept over lower New York.

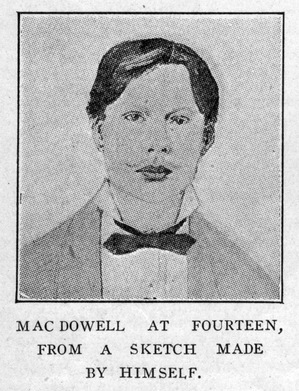

MacDowell’s grandparents were Quakers, and when the composer’s father, Alexander MacDowell, showed signs of a talent for drawing it was repressed as much as possible. It is not surprising then that Edward had the encouragement of his father in both drawing and music. The boy’s first music teacher was Mr. Juan Buitrago, a South American pianist of ability and experience. The child was very versatile, and his music books were frequently decorated with clever sketches and youthful attempts at poetry. In later years his poems became so numerous and so melodious that a collection of his verses was published after MacDowell’s death. So diversified were the boy’s talents that his parents were at a loss to know which one to select for a life career. After Buitrago, his next teacher was Paul Desvernine and then no less than the incomparable Teresa Carreño, who, it will be remembered, had gone to New York from Venezuela when she was little more than a child.

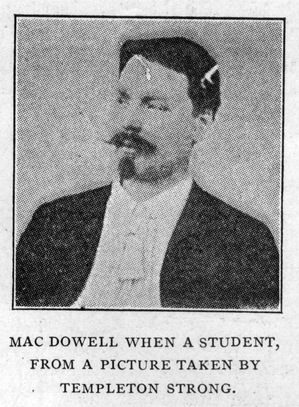

So very marked was the talent of the boy that his parents were advised to supplement his work with a course of study in Europe. Accordingly he set out with his mother for Paris in the early part of 1876. He had little difficulty in passing the examinations for admission to the Conservatory, where he became the piano pupil of Marmontel and the theory pupil of Savard. Among his companions in the conservatory was Claude Debussy. The two young composers maintained a mutual interest in each other’s work in later years.

In 1878 MacDowell heard Anton Rubinstein’s brother, Nicholas Rubinstein, play the Tchaikovski Concerto in B flat minor. He was amazed at the performance, and this led him to believe that in order to reach a similar standard he would be obliged to employ methods somewhat different from those in use at the Paris Conservatoire at that time. Consequently he decided to go to the Conservatory at Stuttgart, then at the height of its fame as a school for pianists.

It did not take long for MacDowell’s acute powers of perception to point out to him that at Stuttgart there was not the atmosphere for which he was longing. The ultra-arbitrary methods at Stuttgart soon disgusted MacDowell and he sought another institution. This time it was Frankfort-am- Main, where Joachim Raff was at the head of the excellent conservatorium endowed by Dr. Hoch. During the intervening summer, however, MacDowell resided in Wiesbaden studying with Louis Ehlert, whose reputation as a writer and as a pedagog was deservedly great. Ehlert wanted MacDowell to study with Von Bülow, but the latter felt that his teaching days were over and wrote a none too courteous letter stating that “he could not waste any time on an American boy.”

At the Frankfort Conservatory MacDowell became the pupil of Raff in composition and Carl Heymann in pianoforte playing. The latter teacher was one of the most sympathetic and artistic of the piano pedagogs of his time and yet he had sufficient disciplinary routine not to be mild with his pupils. MacDowell states in one place that while at Paris the methods of instruction were so exhaustive that they led him to transpose the preludes and fugues of Bach into other keys. At Frankfort, Heymann taught him more in one week than ever before. In Raffhe also found an inspiring artistic friend as well as a teacher. Raft was no weakling in his pedagogical attitude, even though many of his compositions do descend to triteness as others ascend to mastery.

Heymann was so convinced of the greatness of MacDowell as a pedagog that when mental troubles revealed to the German teacher that he would be obliged to leave the conservatory, he suggested MacDowell as his successor. There is something pathetic in the close friendship of Heymann for MacDowell at that period when we remember that our American master was doomed to spend his closing hours in similar intellectual darkness. Jealousies in the faculty however, prevented MacDowell from receiving the post. He was little more than a youth and was likewise an alien. Quite naturally the important position was tilled by a native German teacher.

MacDowell did Commence to teach, however, and among his pupils was that remarkable woman, Miss Marian Nevins, who was later to become Mrs. Edward MacDowell. Through her efforts to preserve the spirit of her husband’s work she has created at Peterboro, New Hampshire, a movement which has won national recognition.

MacDowell at Darmstadt

MacDowell was appointed head piano teacher at the Darmstadt Conservatory, where he taught mediocre pupils for forty hours a week. He also taught a little class of titled and stupid children in the Castle at Erbach-Fürstcnau. Finding the life at Darmstadt tiresome, he resided at Frankfort and rode daily to the smaller city. These long rides on the trains enabled him to devote much time to composition, as well as to German, French and English literature.

In 1882 MacDowell visited Liszt and played his first piano concerto for the master. Eugen D’Albert was at the second piano. It was at Liszt’s insistence that MacDowell’s Modern Suite was given at the Allgemeiner Deutscher Musik-Verein Convention held at Zurich. MacDowell played his first piano suite with pronounced success. This was one of the greatest honors that could have been bestowed upon a young musician, and is characteristic of the artistic liberality with which Germany has welcomed and helped many American artists when they have been worthy of notice.

The following year Liszt again helped him by securing the publication of the first suite and the second suite with Breitkopf and Härtel in Leipsic. MacDowell tried to show his appreciation by dedicating his first pianoforte concerto to Liszt.

In 1884 MacDowell returned to America for a month, during which time he married Miss Nevins at Waterford, Conn. Again back in Europe, the young couple visited London, Frankfort and Paris. He applied for the post of head pianoforte teacher at the Würzburg Conservatory but was fortunate in not receiving it—fortunate because he was compelled to turn his attention to composition, and thereby produced many interesting works. In 1887 we find the MacDowells in their own home on the outskirts of Wiesbaden, where the composer purchased a house with one-half acre of ground. There MacDowell found time to produce some of his lesser known works. The following year, however, he was persuaded to return to the United States, and he sold his cottage to throw himself into the music life of his native land. Settling in Boston, he found the music life much to his liking. Pupils excited by his European prestige literally flocked to him. His orchestral works were regularly performed by leading orchestras. As a soloist he appeared quite frequently in recitals and with the Kneisel Quartet.

In 1894 MacDowell played his second concerto with the New York Philharmonic Society under Anton Seidl. It was then that the New York public and the New York critics opened their eyes and ears to the loftiness of the genius of Edward MacDowell. America at last had a master whose works could be placed upon the programs of great symphony orchestras without any suggestion that they were put their largely through a patriotic desire to foster American musical interests rather than that of catering sincerely to the real preferences of the audience. In fact all of the critics of the hour were unanimous in their praise. Encouraged by this, MacDowell gave two pianoforte recitals in the Concert Hall of Madison Square Garden.

The chair of music at Columbia University in New York is due to the munificence of Mrs. Elizabeth Mary Ludlow, who provided a fund of $150,000.00 for that purpose. In the fall of the same year MacDowell moved from Boston to New York to accept the position of Professor of Music at Columbia. Naturally he gave much thought to this move. His teaching in Boston had been highly successful, and it would have been impossible for him to have accepted more pupils. On the other hand, the post at Columbia provided regular employment and at the same time was possibly somewhat less precarious. His main difficulty lay in the work of establishing the new department, as he gave only about ten hours a week to actual class work.

With systematic sincerity he at first mapped out very clearly in his mind what the department was expected to accomplish and expressed it in the following tenets:

I. To teach music scientifically and technically with a view to training musicians who shall be competent to teach and compose.

II. To teach music historically and aesthetically as an element of liberal culture.

MacDowell was an indefatigable worker, and with his natural conscientiousness the ever-increasing work at Columbia proved too great a strain. His published lectures indicate the great care with which all of his work at the University was done.

Many have advanced the idea that it might have been better if MacDowell had been able to devote all of this time to composition and pianoforte playing, for which he had especially prepared himself. While his piano playing suffered, it is nevertheless a fact that many of his best pieces in certain forms were done during the Columbia days. Among these are the famous Norse Sonata and the Celtic Sonata, as well as the Sea Pictures, which have all brought his genius such high praise.

MacDowell at Peterboro

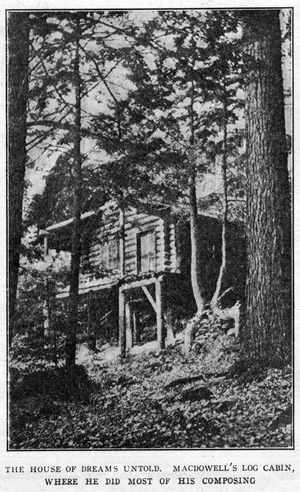

In the same year that he took up the Columbia professorship MacDowell bought a farm property at Peterboro, New Hampshire. With fifty acres of delightful forest and fifteen acres of good farm land there was also a fine old house and some smaller buildings. There in a log cabin in the woods he wrote most of his later compositions. His time was spent between his country home and his winter residences in New York. During his last days he spent much of that sad, sad time at the Westminster Hotel on Irving Place, New York.

The great strain at Columbia forced him to resign in 1904. Instead of resting he continually undertook more and more work, including teaching, which he did largely as a means of maintenance rather than for the love of the work. In 1905 the signals of the tragic end were noticed. Well in body, his magnificent intellect commenced to decay until he became like a little child. He passed on, January 23, 1908, when just reaching those years which find most men in their prime and which might indeed have been his prime if he had taken time for sufficient rest.

As a motto for his last composition, From a Log Cabin, the composer had written: “A house of dreams untold, It looks out over the whispering tree-tops And faces the setting sun.”

These significant lines are now traced on a bronze tablet on the crest of a hill not far from the little log cabin in which the composer wrote down so many of his splendid musical thoughts. What could be more characteristic of MacDowell’s simplicity and his Americanism than the little log cabin in the New Hampshire hills and the unhewed rock that lays above his last resting place?

MacDowell as a Pianist

As we have already noted, it was MacDowell’s original desire to become a pianist. Those who remember his playing well, among whom may be reckoned the present writer, felt that it was rare because of the performer’s wide understanding of the musical dimensions of the masterpieces he attempted to portray and because of the man’s unquestioned sincerity. While his technic was adequate in every way, he did not aspire to shine as a technicalist. His published exercises concern themselves rather with special forms demanding new hand positions than with the conventional scales, arpeggio and octave forms. MacDowell’s playing was characterized by its extreme clearness and beautiful effects achieved by the employment of the pedal. In such a composition as his very powerful March Wind he produced intense stringendo results that were always very impressive. While he frequently played his own compositions in response to popular demand, he was even more conscientious in his interpretations of the masters of the past. Had he done more public piano playing instead of devoting so much time to composition and to teaching, there is no question that we would look back upon him as one of the foremost virtuosos of his century.

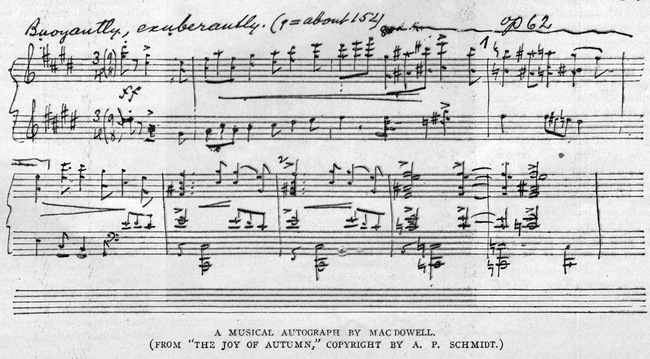

There are sixty-two opus numbers represented in MacDowell’s compositions and some half dozen without opus numbers. Several piano numbers are sets of several pieces. Seventeen numbers are vocal, but these include several collections of from three to six songs. Henry T. Finck goes so far as to rank MacDowell with the very greatest song writers, Schubert, Franz and Grieg. There is no doubt that MacDowell’s inspiration carried him at times to very great heights in his vocal works, and it is difficult for Americans anxiously seeking to find merit in the works of a fellow- citizen to appraise these works severely. It is accordingly very convincing to find European critics among the most enthusiastic admirers of MacDowell as a song writer. Thy Beaming Eyes is doubtless one of the best songs yet produced in this country from the standpoint of its wide appeal and its simple and masterly treatment. There are, however, many other MacDowell works which critics seem inclined to appraise higher than such a song as Thy Beaming Eyes. Such songs as In the Woods, Op. 28, No. 1, or The Robin Sings in the Apple Tree, or The Sea, represent the master’s strong inspiration and his highly cultivated taste in supplying appropriate musical background to the poet’s thought. MacDowell in some instances wrote the verses for his own songs, and some of these are quite as delightful as the music. There are recorded over one hundred compositions for piano, and, as in the case of the songs, there are a few which have met with immense popular favor, such as the Witches’ Dance, Scotch Poem and To a Wild Rose, while others more notable have been neglected. The Concertos and Sonatas, as well as the Twelve Virtuoso Studies (Opus 46), represent the more pretentious of MacDowell’s works and in many ways his highest manifestation of musicianship, but at the same time many of his smaller pieces show inspiration which should not be discounted because of the lack of complexity in their expression. MacDowell’s piano works are exceedingly grateful, in that their performance brings that response from the instrument which the player hears with delight. For that reason they have been widely played by pianists in this country and abroad. Mme. Carreño and Mme. Samaroff are especially famed for their interpretation of MacDowell.

The MacDowell compositions for chorus and orchestra are less widely known than those for voice and piano, but they are nevertheless exceedingly interesting. The Indian Suite, employing aboriginal American Indian themes, attracted wide attention because of the ingenuity of the treatment of the melodies. MacDowell was inclined to resent the great public favor with which some of his works met, feeling all the while that his more worthy compositions should have an audience. It is said that he maintained this attitude toward his earlier orchestral compositions, Lancelot and Elaine and Hamlet and Ophelia.

The MacDowell compositions for chorus and orchestra are less widely known than those for voice and piano, but they are nevertheless exceedingly interesting. The Indian Suite, employing aboriginal American Indian themes, attracted wide attention because of the ingenuity of the treatment of the melodies. MacDowell was inclined to resent the great public favor with which some of his works met, feeling all the while that his more worthy compositions should have an audience. It is said that he maintained this attitude toward his earlier orchestral compositions, Lancelot and Elaine and Hamlet and Ophelia.MacDowell the Man

Those who knew MacDowell were impressed first of all by his absolute sincerity in all that he did, his lack of pose, his detestation of ignorant applause and hisextreme sensitiveness. He was American to the core. This was shown by his love for the primitive in American life and by his fondness for our characteristic native literature, as exemplified in the works of such men of writing genius as Mark Twain and Joe Chandler Harris. Familiar as he was with the literature of three languages, he would often turn to the homely American philosophers with keen delight.

Physically MacDowell was a handsome man. His body was robust and lithe. His strong blue eyes and his firm flesh indicated fine bodily health. Indeed there was a splendid vigor in all his movements, and his person at the keyboard was inspiring and impressive. With his friends he was genial, with strangers perhaps over-retiring. He was a fine conversationalist, ready with accurate and fitting words and not without a touch of that Irish wit which is irreplacable.

MacDowell had many close and valued friends in Europe and in America. Between him and Edvard Grieg there was an especially strong artistic bond, as is shown by their letters. Mr. Henry T. Finck was a great admirer of MacDowell, and this feeling was warmly reciprocated by the composer.

The MacDowell Memorial Association

The MacDowell Memorial Association was organized a few years after the death of the composer, to continue his memory in a manner more helpful than may be done in bronze or stone. Mrs. MacDowell by her tireless efforts has made this institution one of the most notable in the country. Together with the main buildings in which MacDowell resided there are several studios for work purposes, and there artists may go to live for stated periods to carry out their ideas. Although the institution is endowed, the creative workers residing there under very desirable surroundings must of course pay a moderate rate for their support. “Eligibility for membership in the colony is, generally speaking, approved talent vouched for by at least two well-known people, and a declared purpose of specific creative work and adaptability for harmonious coöperation in the life of the colony, which necessarily is largely self-governed.”

Every summer festivals and pageants are given in a great out-of-doors theatre in the woods. These are attended by music lovers and artists from all parts of the country. The MacDowell Choir, of Nassau, New Hampshire, and a Symphony Orchestra from Boston participate. As Mrs. MacDowell’s own contributions, largely from her own lecture earnings, have gone well up into the thousands, the nature of the enterprise may easily be comprehended. May the work of Peterboro prosper richly as it deserves to prosper.

Books on MacDowell

Much has been written upon the subject of MacDowell, and among the best biographical articles are those which have come from the pen of his friend, Mr. Henry T. Finck, and his pupil, Miss Jo-Shipley Watson (editor of the Children’s Department of The Etude). Edward MacDowell, a Study, by Lawrence Gilman, is an exceptionally fine biography of the composer, giving an unusually clear insight to his aims, ideals and accomplishments. In August, 1915, “The Music Student,” an excellent English publication, devoted its entire issue to MacDowell, whose works are universally popular in Great Britain.