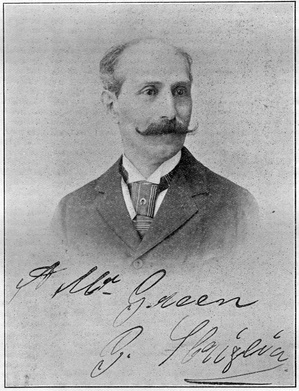

[Mr. J. Edmond Skiff, for a number of years associated with the Batavia State School for the Blind as musical director, has just concluded a year of study in Paris with that veteran maestro G. Sbriglia. Perhaps there is no teacher living at present more prominent in the public eye than this Italian-Frenchman, who has such unique, if not extreme, views on tone-production. As I knew him in my student-days, he represented the very antithesis of the modern popular ideas on vocal technic, and my desire to ascertain the master’s present attitude to the subject prompted me to ask Mr. Skiff for a short article. Mr. Skiff is not a stranger to the readers of the Vocal Department, and we welcome the following response to my request.— Vocal Editor.]

In an unpretentious, though very comfortable, apartment in the Rue de Provence, Paris, lives Signor Sbriglia, one of the world’s famous vocal teachers, whose renown has been largely gained through his work with Mr. Jean de Reszke, the great Wagnerian tenor.

In an unpretentious, though very comfortable, apartment in the Rue de Provence, Paris, lives Signor Sbriglia, one of the world’s famous vocal teachers, whose renown has been largely gained through his work with Mr. Jean de Reszke, the great Wagnerian tenor.

Sbriglia is a student of the Naples Conservatoire, from thence making his début in the opera “Brasseur de Preston,” by Braci. After some time in Naples he toured Europe, singing in all the grand-opera houses, and in 1866 went to America, singing with the Italian and English Opera Company in the United States and Mexico.

About twenty-five years ago he settled in Paris, devoting himself entirely to teaching. His first pupil he brought out in Paris was Otello Nonvelli, an Italian who made his debut in the tenor rôle in “Martha,” at the Italian Opera, which is now extinct, with Edouard de Reszke. His success was so great that Jean de Reszke, who was at that time singing baritone parts without success, being, in fact, so despondent that he contemplated leaving the stage, went to Sbriglia requesting lessons. Sbriglia assured him that his voice was of the true tenor quality, and that he should give up baritone work. His study with the maestro covered about six years, and all the world can now testify to the accuracy of Sbriglia’s diagnosis.

Shortly after, Josephine de Reszke, a sister of Jean and Edouard, came to him. She it was who created the principal role in Massenet’s opera, “Le Roi de Lahore,” at the Grand Opera in Paris. From Paris she went to Spain, where she had immense success. She left the stage to be married to Baron de Kronenberg; unfortunately she died in Poland a few years after her marriage, leaving two little children.

Among his other celebrated pupils have been Lillian Nordica, Sibyl Sanderson, Fanchon Thompson; Miss Phebe Strakosch, soprano, daughter of the impresario, Ferdinand Strakosch, and cousin of Adelina Patti, singing in Spain, Italy, London; Mr. Plançon; d’Aubigne; M. Castleman, now first tenor in the Opera at Algiers; and Madame Aduing, who sang at the Grand Opera, Paris, for five years, and also in Italy and London. After singing all the lyric operas, she devoted herself to Wagner. She enjoyed much favor as the soloist at the Colonne and Lamoureux concerts. Among his present pupils is a Miss Markham, who has recently gone to Bayreuth to study Wagner rôles with M. Sem, a Swedish tenor; Mr. William Hughes, of Washington, D. C., a possessor of a magnificent basso cantante voice; Mr. Whitefield Martin, of New York, a tenor of much promise, who has given up a fine clientele of pupils to devote his time to study for the opera.

Personally S. Sbriglia is very agreeable, a short man, with a very full chest, dark hair, and eyebrows, looking his nationality. In his teaching he sits at an upright piano with a large mirror on the wall back of him, while the pupil stands back of the piano, where he can complacently view himself in the mirror and also watch at the same time the various expressions of the maestro’s face. He says very little during the lesson; his three great points being the extreme high chest, the voice placed entirely in the mask of the face, and the protruding of the lips. He places great stress on the very high, fully-developed chest, and the pupil’s first lesson will in most cases consist partially in an admonition to at once procure a pair of dumb-bells, and an oft-repeated expression is: “Beaucoup de dumb-bells.”

When asked how he teaches his pupils to breathe, he replied: “I don’t breathe; I build up the chest.” He points with pride to some portraits of his pupils taken “before arid after,” showing great development, and their names are familiar ones to the opera-goer. If one wishes to know thoroughly all the resources of the master, one must be content to stay with him a long while, for he imparts his information very slowly, and even the pupil must gain it more by intuition than by word of mouth. He is not a musician, but he does make his pupils sing as far as the mechanism of the voice is concerned; for interpretation and the higher art, he is quite willing the pupil should go to some of his “confrères.”

No article would be complete without a mention of Madame Sbriglia, who, by the way, is an American, for she is a very important part of the studio. She it is who arranges all the pupils’ lesson-hours, attends to the financial part, and plays all the accompaniments except for the exercises at the beginning of the lesson, which he industriously plays (?) with one finger. Madame takes great interest in all the pupils, is always ready to help in any way possible, and in many cases smoothes out the wrinkles that come from the master’s presence. She is a busy woman, for she must be on call, as it were, during the entire teaching-hours, which, however, are not so long as in former years, as he now refuses to teach more than five hours each daily. These hours being from 9 to 11.30 and 3 to 5.30, and the pupil who has not engaged lessons early in the season must be willing to take a lesson when some regular pupil is unable to come, and there are always plenty of pupils waiting to fill in a vacancy.—J. Edmond Skiff.