By ARTHUR ELSON

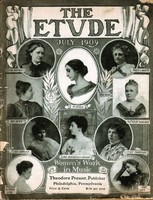

Author of “Women’s Work in Music”

THAT women have had much to do with music is shown, first of all, by the fact that the patron (or matron) saint of the art was a woman. Not everyone thinks that St. Cecilia was a real personage, but she actually did exist, in the second or third century. The facts are somewhat apocryphal, but it is stated that about the year 230 A.D. a noble Roman lady of that name, a Christian, was forced into marriage with a pagan named Valerian. She finally converted him and his brothers, but all were martyred in a subsequent persecution. Even then she would not have been connected with music but for the passing statement that she often united instrumental music with that of her voice in sounding the praises of the Lord.

Women are well represented in the various mythologies in connection with music. The Muses and Sirens are well known. India, too, ascribes its favorite musical instrument, the vina, to Brahma’s consort Sarisvati. The various scales were represented by nymphs, and when Krishna came to earth sixteen thousand of these young ladies sang to him, each in a different

mode.

In the folios of Lepsius is a picture of an ancient Egyptian institution resembling our own conservatories of music. It represents a course of music in the school of singers and players of King Amenhotep IV years before the Christian era. There are large and small connected rooms, with furniture and musical instruments. In one room a teacher sits listening to a girl singing, with another girl playing the harp for accompaniment, and a third one regarding the teacher attentively. Another room shows two girls practicing a dance with harp music. A third room shows a young lady leaving her harp and sitting down to lunch with a friend. Doubtless these girls and many others did some composing, even if only in the form of improvisations.

SAPPHO.

In Greece, as in so many ancient lands, women did not go about as now. Probably music played an important part in driving away the tedium of their stay-at-home lives. But there is one name in Greece that is famous even now—that of Sappho. Very little is known of her life, and that little is not certain. She was born near the end of the seventh century B. C., either at Mytilene or at Eresos, in Lesbos. She lived in the former place, where she grew into fame through her poetry. She and Alcæus were the two leaders of Æolian poetry, and a friendly rivalry existed between them. About the year 6oo B. C. she fled to Sicily to escape some unknown danger. According to many, she met death by throwing herself off the Leucadian Rock because her love for Phaon was unrequited. But there was an annual ceremony of casting from that rock a criminal, with birds tied to him to break his fall. From this grew the idea of unfortunate lovers leaping from the rock into the sea, and the expression may have grown symbolic, like our phrase “Crossing the Rubicon.”

It is fair to call Sappho a musician, for in her time poetry and music were not separated. Modern histories often call the old Greek music primitive and simple, but that statement overlooks the great possibilities of the Greek instruments, even in solo work. Sappho was probably an excellent composer, and at Mytilene she gathered a large circle of the most educated young women, who were her pupils in poetry, music and personal cultivation. The power of her poetry was made evident by its effect on Solon, the lawmaker. Hearing one of her works for the first time, he expressed most ardently the wish that he might not die before having learned such a beautiful song.

Other poetesses (and therefore musicians) in Greece were Myrtis and Corinna, both contemporaries of Pindar. In later times music fell into the hands of the lowest classes. The same was largely true of Rome, though there the art was kept alive also by slaves, who were usually much more cultivated than their masters. Finally the Christian Church set the ban on woman singers. Altogether it is no wonder that we find no great woman composers in those times. In Northern Europe, where wives were bought like cattle, the position of slaves was certainly not enviable. The laws of that time provided that if a female slave were convicted of theft she should be burned alive by eighty others. Per contra, if a woman scourged her slave to death, she should do penance! Here, too, conditions were hardly ripe for woman composers.

ENGLISH GLEE MAIDENS.

Chivalry and the code of the Troubadours placed women on a higher plane. In common with men, they were able to sing their own music to the various poetic forms that they composed. The Glee-Maidens, who flourished for some time in England, were decidedly interesting and romantic figures. Often they would wander about alone, with only the escort of a pet dog or a goat, or perhaps a dancing bear. They wore bright colors, often adorned with silver, and on their feet were leather buskins. They were welcome in castle and monastery as well as village and town. In the latter they would mount some slight knoll and entertain a motley gathering with voice and violin. They often became famous, and we read that a certain Adeline, one of their number, was rewarded with an estate by William the Conqueror.

But the greatest of them all was Marie de France, a Jongleuse of the time of Henry III. Born probably in Breton, she learned Latin as well as English. Her first set of lays, in French verse, won instant admiration in castle and court. Twelve of her songs are now in the British Museum, among them one treating the Arthurian legends in remarkably beautiful fashion.

With the decay of the Troubadours and Jongleurs came the beginning of the various schools of counterpoint, where at last may be found women whose works can be heard and enjoyed to-day. There is a saying that music was horizontal formerly, but is now vertical. The flowing part-writing is aptly described by this, but the contrapuntal music is not yet shelved; so we may still listen to the motets or madrigals of such women as Maddalena Casulana or Vittoria Aleotti in Italy, Madelka Bariona in Germany, Clementine de Bourges in France, or Bernarda de Lacerda in Portugal. At a later date Francesca Caccini, daughter of the early opera composer, became the idol of her city, and grew renowned in poetry as well as music.

After the contrapuntal school had culminated in Bach, music was turned into new channels, more as we see it now. Woman composers have come thick and fast, in spite of much absurd prejudice against them. It is hard to see why women should not always have been allowed to compose, as there is nothing unfeminine in writing music. But even in the last century such men as Mendelssohn and Rubinstein opposed the idea. As is well known, Mendelssohn was properly punished, for he had to confess to Queen Victoria that the song “Italy,” which she liked and credited to him, was really the work of his sister.

An interesting female figure in the eighteenth century is Maria Theresa von Paradies. Although totally blind, she became a pianist of the first rank, gifted with powers of the most sympathetic expression. Her memory was phenomenal, for she could play at least sixty concertos and any number of smaller pieces. Her compositions showed unusvery (sic) popular fairy opera, “Rinaldo and Alcina;” the melodrama. “Ariadne and Bacchus,” and the pastoral operetta, “Der Schulcandidat;” also a piano trio, a number of sonatas, some cantatas and many songs. Mozart gave high praise to these works.

A PUPIL OF HAYDN.

Marianne Martinez, a pupil of Haydn and Porpora, was another gifted composer, whose oratorio, “Isacco,” met with deserved success at Vienna in 1788. She has other oratorios, a mass, overtures and even symphonies to her credit.

The most famous German woman composer of the nineteenth century was undoubtedly Clara Schumann. As Clara Wieck she became a famous pianist. Her marriage with Schumann, after his lawsuit against her father to show that he could support her, brought about a condition of idyllic happiness reflected in the works of both. The list of her own compositions includes many songs and piano solos, some violin pieces. a piano trio and a piano concerto. They are all of excellent quality, and a good song is more to be praised than an overswollen symphony.

In the early years of the nineteenth century Emilie Zumsteeg became a wonderful sight reader, able to play full orchestral scores on the piano with ease. Her home was the center of a brilliant circle of friends, including Weber, Hummel and Lindpaintner. Her largest work was an overture to “Die Geister Insel,” but she was best known through her many beautiful songs.

Fanny Mendelssohn, like her brother, had the delicate hands which caused people to say that she had “Bach-Fugue fingers.” Both before and after her marriage to the painter, Wilhelm Hensel, she led a life of happy activity, but she would probably have composed much more than she did if her brother had not opposed any attempts at publication. As it is, her work is limited to a few songs and piano pieces and a piano trio.

Other women composers of note in Germany were Leopoldine Blahetka, the Austrian pianist, whose chamber music is excellent; Emilie Mayer, who put really good music into her overtures and symphonies; Aline Hundt, who died at twenty-four, after writing choral and other works; Agnes Bernouilly, whose orchestral works have been frequently given; Louisa Adolpha Lebeau, gifted and ambitious, who had worked in overture, concerto, oratorio and many other forms, and Ingeborg von Bronsart, born at St. Petersburg, but of Swedish parentage. She it was who came to Liszt at eighteen, a dazzling vision of Northern beauty, and astonished him by her playing of a Bach fugue. “You don’t look like that,” he cried in surprise. “I should hope I didn’t look like a Bach fugue,” was her famous reply. She wrote three operas, a number of choruses and many excellent songs.

FRENCH WOMEN COMPOSERS.

France has been more prolific than any other in producing good women composers. Most popular to-day is Cecile Louise Stephanie Chaminade. She has written large works, such as her lyric symphony with choruses, her piano concerto and the ballet “Calirrhoe,” from which some of her best-known pieces are taken. But it is by her shorter piano works and songs that her success is made. Their piquant style and daintiness of modulation give them a charm that is unique in music. The “Scarf Dance” and “La Lisonjera” have become most popular, but the “Contes Bleus,” for piano, ‘ and such songs as “L’Anneau d’Argent” or “Si j’étais jardinier” are of greater musical worth.

Augusta Holmes was another famous woman in France. Of Irish parentage, she early became a native of Paris, where she died in 1903. When only eleven she conducted a quickstep of her own, played at Versailles. Her operas include “Hero et Leandre,” “Les Argonautes” and “La Montagne Noire.” She has written symphonies, but she is best known through her large symphonic odes with chorus. The “Ode Triomphale,” for the Paris Exhibition of 1889, was one of the best of these. Its success was so marked that the city of Florence ordered from her a work, the “Hymne à la Paix,” for the Dante festival. Her impressions of Italy are recorded in the suite “Au Pays Bleu.”

Marie Felice Clemence de Reiset, Vicomtesse de Grandval, is another name no less famous than it is extensive. She excelled in opera, and her Stabat Mater won high praise. Jean Louise Farrenc, of a somewhat earlier period, wrote such good works in her youth that Schumann fell into the error of suspecting that they were not wholly her own. She worked well in the classical forms—symphony, overture, chamber music of many varieties, and violin and piano sonatas. Louise Angelique Bertin, of the same period, made many successes in opera and wrote verses that won a prize from the French Academy.

Pauline Viardot-Garcia was sister of Malibran and daughter of Manuel Garcia. She was with him when a band of Mexican train robbers held him up, relieved him of his cash and added insult to injury by making him sing for them. But they escaped further trouble and returned to Europe, where Pauline found a career of fame and honor as an opera singer. On leaving the stage she taught and at Baden-Baden. Her works include operettas, piano solos, violin pieces and some excellent singing exercises. Her daughter. Mme. Heritte, is also a composer, having produced operas, string quartets, songs and piano works.

Gabriella Ferrari, pupil of Gounod and Dubois, has written good orchestral suites and a comic opera, besides the usual piano pieces and songs. Her “Fantasie Symphonique” and “Jeanne d’Arc” are often performed. Among French opera composers Elizabeth Claude de la Guerre, admired by Louis XIV, made a success with “Cephale et Procris” in 1694. In the next century Henriette de Beaumesnil occupied the foremost place. Lucile Grétry, daughter of the composer, produced two operas before her untimely death at twenty-four. Edme Sophie Gail-Garre flourished early in the nineteenth century, while Pauline Thys met success in its later decades. Marguerite Olagnier is another good opera composer, whose “Sais” and “Le Persan” are very beautiful. Marie de Pierpont was a talented writer for organ. Another great organ composer of earlier date was Louise de la Hye, a grand-niece of Rousseau. She died at twenty-eight, a professor of harmony in the Conservatoire. Marie Bigot was a piano composer and friend of Beethoven, while Marie Pollet and Theresa Demar wrote for the harp.

ENGLISH WOMEN COMPOSERS.

Women composers did not become numerous in England until after 1750. In the nineteenth century we begin to find several, such as Ann Shepard Mounsey, whom Spohr spoke of as a child prodigy; Mrs. Charles Barnard, known as “Claribel;” Virginia Gabriel and Charlotte Sainton-Dolby, the friend of Mendelssohn. All these, however, wrote in a style too simple and sentimental. The songs of Ellen Dickson (“Dolores”) were somewhat better.

The foremost woman composer of England was undoubtedly Alice Mary Smith, afterwards Mrs. Meadows-White, who made composition her life- work. Her music is always clear and well-balanced in form, with excellent thematic material and an expressive charm of melodic and harmonic beauty. In the larger forms she has written two symphonies, four overtures, a clarinet concerto and an introduction and allegro for piano and orchestra. Her chamber music, also successful, includes four piano quartets and three string quartets. Of her published cantatas, the “Ode to the Northeast Wind” is the strongest. Her many part-songs are of rare charm, as may be seen from the duet, “Oh, That We Two Were Maying.” She died in 1884, at the age of forty-five.

Among other orchestral writers in England Edith Greene wrote a symphony that was well received. Amy Elsie Horrocks, the pianist, produced the orchestral legend “Undine.” Edith A. Chamberlayne has composed two symphonies. Edith Swepstone brought out some movements of an unfinished symphony, and the overture “Les Tenebres.” Rosalind Ellicott wrote three overtures and a fantasie for piano and orchestra. Better known than these is Dora Bright, whose two piano concertos were praised by critics for “original fancy and melodious inspiration of a high order, coupled with excellent workmanship.” Her fantasie for piano and orchestra was the first work by a woman to be given by the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Ethel Smyth is now well known because of her operas, “Der Wald” and “The Wreckers,” the latter rather vehement in style, but performed successfully in London.

Famous song writers are England’s most recent product. Foremost is Liza Lehmann (Mrs. Herbert Bedford), who became famous through her cycle, a Persian Garden,” with words from Omar Khayyam. This is her best work, full of strong expression, moving pathos and exquisite beauty. Frances Allitsen passed a lonely youth in a little village where, as she says, “if a girl went out to walk she was accused of wanting to see the young men come in on the train, where the chief talk was on the subject of garments, and the most extravagant of excitement consisted of sandwich parties.” At last she came to London, where she taught in the day to earn money for her evening studies. After braving all difficulties she won a well-deserved success. Besides her songs, her two overtures, “Slavonique” and “Undine,” were both successful. Mrs. Rhodes (Guy d’Hardelot) is another of the gifted song writers, who has written for Mme. Calve some clever acting songs, such as “The Fan.” Maude Valerie White, of an earlier generation, wrote many songs of excellent workmanship. Agnes Zimmermann has written many beautiful violin works.

AMERICAN WOMEN COMPOSERS.

In the United States Mrs. Beach stands at the head of the list, as she has done much in the large forms. Her “Jubilate” cantata was well received at the Chicago fair. Her Mass and Gælic Symphony have also been performed. Her piano works, songs and violin sonata are well known in many countries, especially in Italy. Margaret Ruthven Lang has written several overtures and orchestral arias, as well as many beautiful songs and piano pieces. Mme. Helen Hopekirk’s piano concerto is a worthy work, dignified and musicianly. In the smaller forms America has a host of composers who are becoming better known every day. The native list is, however, too well known to require detailed description.

Other countries have their composers, too. In Italy Carlotta Ferrari and the Countess Gilda Ruta have produced operas, while Eva dell’Aqua writes good songs. Maria Teresa Agnesi wrote in almost all forms in the eighteenth century. Holland has Catharine van Rennes and Hendrika van Tussenbraek for songs and Cornelia van Oosterzee for more ambitious works. In Belgium Juliette Folville takes high rank with orchestral suites and a violin concerto. Norway has Agathe Bacher-Gröndahl, and Sweden Elfrida Andrée, while from Venezuela comes our own spirited Carreño.

From these names it is evident that women are now freely allowed to compose. Whether they will ever equal men is a little doubtful; many claim that they will always lack the virility of a Beethoven. Liza Lehmann thinks that women are handicapped even by the lack of physical strength. As yet there has been no woman composer of the very highest rank, but that certainly is no reason why there may not be one in the future.