HENRY HERZ may be considered as one of the greatest pianists of the world. An Austrian by birth he went to Paris when a mere child, growing up a naturalized Frenchman. At the Paris Conservatory, where he was educated, he took the first prize four consecutive years. Herz was gifted as a composer, as well as pianist. As pianist, he toured the world, meeting with success artistically and financially. His technic was of a brilliant, showy nature, which all of his compositions plainly show. The French are known to be an artistic, showy people, and Herz catered in his compositions to their tastes. He wrote many fantasies on the popular opera airs of the day, a few of which are still played. His “Lucia” is considered the best of the kind extant. It is a piece I consider equal to any of the fantasies of Liszt, Thalberg and other modern composers, as a show piece for its musical qualities. Herz was quite a prolific composer, leaving many fantasies, three concertos and some valuable etudes. Herz concertized in America at a time when good piano playing was but little known or appreciated, consequently is less known than many of the later arrivals who could not approach him technically or musically. Strange as it may seem, he made almost his greatest reputation on his variations of “The Last Rose of Summer,” which is not a difficult piece. He amassed a fortune by his concerts, which he invested in the manufacture of pianos, and which stand deservedly high, in France. He lived to a ripe old age.

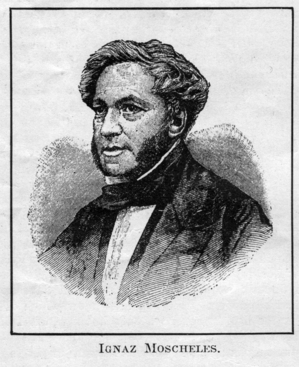

Moscheles made a fine pianistic reputation in Paris, Berlin and London. He concertised extensively, and at one time was considered the best pianist in the world, although this reputation was of short duration. He did not belong to the brilliant, showy school rep resented by Liszt, Thalberg and Herz, but was content to play a more quiet school of music, mainly of the old classic masters. He was a true disciple of Bach, Mozart, Clementi and Beethoven, being looked upon as authority on these masters’ works. His concertos in E major and G minor have been played a good deal, while his characteristic etudes, Op. 70, are standard all over the world. They are a stepping stone between Cramer, Clementi and Chopin. Moscheles lived in London many years, where he often appeared as pianist and director of the orchestra. He had J. B. Cramer for a contemporary—a man of finished technic and author of eighty-four studies that are considered necessary to a good pianistic education. He was a warm friend of Mendelssohn, and when the latter founded the Leipzig Conservatory, he chose Moscheles as the chief piano teacher, a position he held for more than fifty years. As a man and teacher he was much beloved by all who came under his instruction. Moscheles was the last of the noted pianists who played octaves with a stiff wrist, and I have often wondered how he did them so well.

Adolph Henselt has been considered by many as the equal of Liszt and Thalberg. He lived in the same time. The reason he is not more generally known is, that he was so timid and nervous that he could not play before the public, therefore did not travel as a concert pianist. Those who were fortunate enough to hide behind his doors, or listen under his windows, say that his playing was truly wonderful. For many years he was director of the St. Petersburg Conservatory ; he died there a few years since while still in the harness. He became very old, but held his pupils to the last. It is a conceded fact, that one does not know how to teach successfully before he has had thirty or forty years’ experience. Henselt has left many elegant pieces, notably a concerto in F, a trio and 12 etudes, Op. 3 and 5.

Dreyschock

Alexander Dreyschock, a Bohemian, was one of the world’s greatest pianists. His technic was something marvelous, especially that of his left hand. His octave playing was a standing marvel to all the great pianists, who could never quite understand how he did it. He was also equally expert in thirds and sixths. He was not only a bravura pianist, but he could play Beethoven’s concertos with great skill and power. I had the pleasure of hearing him play twice with the celebrated Gewandhaus Orchestra, of Leipzig. He played the Beethoven G major concerto in one and the E flat at the second concert. I also heard him in a miscellaneous concert, when he played a concerto of his own. I remember how Moscheles, Reinecke and David kissed his marvelous left hand after the concert was over. Moscheles took hold of it and shook it back and forth, to see if it was like other men’s hands. At that time I had not heard Liszt, Rubinstein or Von Bülow. and I thought him the greatest player on earth. At this late day, my opinion of his playing octaves, thirds and sixths has undergone no change; I have never heard these excelled by anybody. The greatest demonstration I ever witnessed over a pianist was when he played his “God Save the Queen,” for the left hand alone, at a Gewandhaus Orchestra concert. Men and women stood up on their chairs and shouted “Bravo! bravo! bravo!” until it seemed as if the roof of the building would tumble in. Although against the rules, he was permitted to play four recalls, and then the people were not satisfied. The conservatory bigots criticised him for playing his own compositions, and for what they termed his hard, dry touch ; yet, I have never heard his musical tone surpassed, except by de Pachmann when he played his first series of Chopin recitals in Boston. Dreyschock was extremely popular with the Londoners, where he played several seasons in succession. After concertising for more than thirty years he settled in St. Petersburg, becoming the head of the great conservatory there. He held this position several years, but, his health failing, he yielded to the advice of physicians and went to Italy, where he died a few months later. Dreyschock composed a great deal, but his music was never very popular, and no one hears it to-day. Like many other noted artists, he had his brief honors and applause, but was soon forgotten.

de Mayer

Leopold de Meyer is considered one of the world’s greatest pianists. He was a man of powerful physique, and his playing entered largely into the nature of the man. He was much admired in Europe and in this country by people who love to be astonished with velocity and noise. He possessed both of these qualities in a large degree. His brilliant technic and great power attracted those who desire more technic and noise than music. He visited the United States three times. I heard him on the occasion of his last visit and thought him a sledge-hammer pianist. His velocity and power ‘astonished me, his playing was attractive but unmelodious. He left no lasting musical reputation here.

Mayer

Carl Mayer of Dresden, hardly known here, was a most finished and elegant pianist as well as composer. He made many concert tours in Europe, being greatly admired for his elegant musical tone and general excellence of rendering his music. He was the writer of some beautiful pieces, not surpassed by any of recent date. His “Toccata” in E major is very fine, while many of his studies are chaste and beautiful. Opus 31 and 61 ought to be known by every good pianist.

Von Bülow

Von Bülow, the greatest of Bach, Beethoven and Brahms exponents, is so well known that there seems to be no occasion for recounting his many acquirements. Von Bülow was one of the few great pianists who did not develop his talent early in life, for he did not begin the earnest study of the piano until after he was twenty, and then did not feel sure of making a success. He studied technic, including Czerny, Cramer, Clementi, Kullak and Chopin etudes with Louis Plaidy, then placed himself under Liszt with whom he remained five years. He was a small man, effeminate in physical looks, but possessed nerve force and strength to a high degree. His hands were so small he could hardly reach an octave, yet he could play octaves and extended chords with astonishing velocity and power.

Von Bülow’s technical facility was perfect—there were no difficulties he did not fully surmount, lie played Beethoven’s sonatas as no one ever did before or since. The same may be said of Bach’s and Brahms’ compositions. He was the coolest, most self- possessed man I ever saw at a piano. He could play every piece of Beethoven from A to Z, and tell you exactly where to find each note without consulting the printed copy; his memory was prodigious and vast. When a man can play all Beethoven’s sonatas without a score before him in five consecutive concerts, he is worthy of being called great. Von Bülow could not only do this, but could direct the nine symphonies of Beethoven, and tell the members of his orchestra where each note could be found without consulting the score. Von Bülow was intended for the law, but left that profession to study music. He visited this country three different times; the first and second as piano soloist,, but the third was mostly devoted to conducting some symphonies in New York. He made Beethoven’s sonatas known in all the large cities of the world through his recitals. He played all of them twice in Boston in two consecutive seasons, requiring five recitals each season. He is deserving of lasting honor and praise for his good work by all lovers of the best in music. No pianist has played so much music from memory as Von Bülow, not even excepting the great Liszt.

Jaell

Alfred Jaell, who visited this country in 1855, was a remarkably good pianist. He came to Boston at tin- request of the Germania Orchestra, that gave Saturday afternoon concerts in Boston Music Hall for a number of seasons. He played concertos with this orchestra, but was heard more in the showy fantasies of Thalberg, Blumenthal and D’Albert. His technic appeared to be perfect in all respects. He made Boston his home for two years, winning friends, fame and money. Inducements were offered him to become a permanent resident, but his ambition to live in Europe, to play in the great capitals, was so powerful he could not resist the temptation, and he returned to Germany, making Hanover his permanent home, although, like nearly all the great pianists, Paris was also his residence, where his playing was greatly admired. One season in Paris he played Liszt’s arrangement of “Tannhäuser March” in ten consecutive concerts. Returning to Germany, he had engagements with all the best orchestras of the continent. Unlike many of the great pianists, Alfred Jaell was a lovable man, and without any of their eccentricities. He was not a prolific composer, and has left no compositions of note.