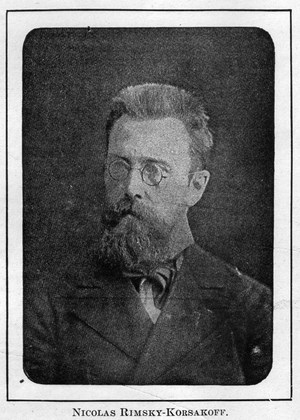

In spite of the many brilliant achievements of the younger school of Russian composers, the unquestioned recognition accorded to Rachmaninoff, Scriabine, (who has been for some months a resident of New York), Ippolitoff, Ivanoff and others, there is no one who can successfully dispute the claim to pre-eminence attained by Rimsky-Korsakoff. He has led an artistic life of great activity and breadth; he has not only a long list of works which attest the versatile nature of his gifts as a composer, but by his long and arduous service as a teacher he has been of incalculable benefit to the cause of musical development in Russia, and many of his pupils have international reputation.

Nicolas Andreievitch Rimsky-Korsakoff was born March 18th, 1844, at Tichvin, in the government of Novgorod. Here he lived up to the age of twelve, and his early experiences in hearing the folk-songs of the peasants, in becoming acquainted with old Slavonic customs, and traditional mythology of the peasants, were extremely important in shaping his later career. At the age of nine he attempted composition without any theoretical knowledge.

However, fifty years ago a musical career was out of the question for the son of well-to-do parents, so he was sent to the naval school at St. Petersburg, where he completed the course in 1862. Before this, however, he had met with Balakireff, who played so important a part in the development of the new Russian school, also the friend and adviser of Tchaikovsky, and actually began the study of music with him.

Balakireff gathered around him a select company of musicians of advanced views, among them Borodine, who was a chemist and army surgeon; Moussorgsky, an army officer; Cui, a professor of fortification; Stassoff, the critic of art and music, who died recently at an advanced age, and others. Their meetings were devoted to the study of master works of various epochs, especially the moderns, and to ardent discussion of the vital principles of musical art.

In the meantime, Rimsky-Korsakoff had entered the navy; according to one account he voyaged at one time along the American coast. Nevertheless he found time even on board ship to pursue his musical studies. In 1865 his first symphony, Op. 1, also the first Russian symphony, was given under Balakireff with considerable success. It was somewhat immature and showed lack of experience, but it also gave evidence of striking talent. Later this symphony was not only partially rewritten but transposed into an easier key.

In the meantime, Rimsky-Korsakoff had entered the navy; according to one account he voyaged at one time along the American coast. Nevertheless he found time even on board ship to pursue his musical studies. In 1865 his first symphony, Op. 1, also the first Russian symphony, was given under Balakireff with considerable success. It was somewhat immature and showed lack of experience, but it also gave evidence of striking talent. Later this symphony was not only partially rewritten but transposed into an easier key.Ultimately he abandoned the navy to devote himself entirely to music. He was appointed professor at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, where he has taught almost uninterruptedly ever since. He was inspector of marine bands from 1873 to 1884. He taught at the Free School of Music founded by Balakireff, and moreover acted as its director from 1884 until 1887. He was assistant conductor of the Imperial Orchestra in 1883, and from 1886 to 1901 he was one of the conductors of the Russian Symphony Orchestra in St. Petersburg, now conducted by Liadoff and Glazunov. He has also conducted concerts of Russian music at Paris and Brussels. He has recently been one of the conductors at a series of five concerts of Russian music in Paris.

As a composer, Rimsky-Korsakoff is known beyond Russia chiefly by his brilliant, skilfully instrumented and imaginative orchestral pieces. In addition to the symphony mentioned above, he has composed two others, “Antar,” Op. 9, highly commended by Von Bülow, given at St. Petersburg in 1868; at Magdeburg, under Arthur Nikisch, in 1881; a symphonic poem, “Sadko,” Op. 5, after a Russian legend, composed in 1867, said to be the first Russian symphonic poem. It was afterwards revised in 1891, and published in the following year. “A Fairy Tale,” Op. 29, an extremely brilliant “Spanish Capriccio,” Op. 34, a suite “Scheherazade,” Op. 35, the subject being taken from the “Arabian Nights Entertainments,” which has been played far and wide in Europe and America; an overture, Op. 36, “The Russian Easter,” on Russian church themes, also widely known, and other interesting works; several suites arranged from the operas “Mlada,” “The Snow Maiden.” “May Night,” “Christmas Night,” “The Tale of the Tsar Sultan,” “A Night on Mount Triglaeff” (the third act of “Mlada,” arranged for concert performance). Rimsky-Korsakoff is a master of orchestral resources, the chief characteristics of his works are the adroit use of folk- themes, varied and striking rhythms, and poetic and highly colored effects in instrumentation.

In Russia, Rimsky-Korsakoff is most highly prized for his works for the stage, which number fourteen up to the present time. Many of these are on legendary or mythological subjects of a fantastic or imaginative character, presenting a heroic popular tale. Such an opera is called opera builina in Russian. For this reason Rimsky-Korsakoff’s operas are exceedingly popular in Russia, for they embody characters in Russian mythology familiar to all, and also introduce many old Russian customs and ceremonies, such as the old Slavonic sun-worship, choral dances and many other quaint and individual ideas.

Thus it is obvious that these operas have a significance to Russians which would be lost on a foreign audience. Among Rimsky-Korsakoff’s works for the stage are: “The Maid of Pskoff,” (1868-1872), revised in 1894, and given in St. Petersburg in 1895; “May Night,” (1878-79) ; “The Snow Maiden,” (1880- 1881) ; “Sadko,” on the same subject as the early symphonic poem, (1895-1896) ; “Mozart and Salieri,” dramatic scenes based on the rumors of the rivalry of Salieri and his alleged poisoning of Mozart, (1897) ; “Vera Schelaga,” (1898) ; “The Betrothed of the Tsar,” (1898) ; “The Tale of Tsar Sultan,” (1899-1900) ; “The Immortal Katschtschei,” (1901-1902) ; “Pan Voyevod,” and finally the latest opera given in St. Petersburg, on February 20th, of the present year, “The Legend of the Invisible Town of Kitege and of the Virgin Feovonia,” founded on a tale of Russian mythology.

While it is unlikely that we shall ever hear a performance of an opera by Rimsky-Korsakoff in this country, and while it is difficult to obtain even a piano score of one of them, it is essential to a just appreciation of Rimsky-Korsakoff to recognize the enormous popularity of these operas through the employment of these old and picturesque legends of Russian mythology. He almost becomes a bard who sings epics of national significance. There have been few performances of Rimsky-Korsakoff’s operas outside of Russia, but “May Night” was given at Frankfort, May 3d, 1900, and “The Betrothed of the Tsar” was given at Prague, December 4th, 1902, Rimsky-Korsakoff has been a prolific composer of songs, of which he has published more than seventy. The few that are obtainable in this country do not seem characteristic of his great talents, yet some of them have been highly praised. In the direction of piano pieces there are twenty-one pieces including Op. 10, Valse, Intermezzo, Scherzo, Nocturne, Prelude and Fugue, six variations on the name B-A-C-H; Op. 11, Impromptu, Novellette, Scherzino; Etude; Op, 15, Valse, Romance, Fugue; Op. 17, six Fugues; Op. 38, Prelude Impromptu, Mazurka. In addition, there is a concerto in C sharp minor, Op. 50, dedicated to the memory of Franz Liszt.

In his piano music Rimsky-Korsakoff does not shine; it is, on the whole, rather mediocre. The Impromptu, Op. 11, No. 1, is of negative value; the Novellette, Op. 11, No. 2, is effective as a wrist study; the Scherzino, Op. 11, No. 3, gives an excellent opportunity in accurate and rapid execution; the Etude, Op. 11, No. 4, is pretty and not hard, a study in sixths. The Romance, Op. 15, No. 2, has been revised and edited by Edward MacDowell. It is graceful, but not highly individual. The six fugues, Op. 17, are doubtless the result of a severe study of counterpoint, which he undertook to correct his early influences. For Rimsky-Korsakoff began with the moderns, Berlioz and Liszt; he afterwards felt the need of a more thorough schooling, and wrote, during one summer, more than sixty fugues and a large number of contra puntal exercises.

In addition, he has written choruses, with and without accompaniment, cantatas, etc. He has published a text-book on harmony, and two collections of folksongs. With Cui, Borodine and Liadoff, he collaborated in the variations entitled “Paraphrases,” which Liszt commended highly; he has written various occasional pieces for quartet. He orchestrated Dargomijsky’s opera “The Stone Guest,” also much of Borodine’s opera “Prince Igor;” he has edited much of Moussorgsky’s music, including selections from the operas “Khovantchina,” and “Boris Godunov,” the orchestral fantasie “A Night on Bald Mountain.” With Glazunov he has prepared an edition of Glinka’s orchestral works. In addition to his intense activity as a composer he has had many celebrated pupils to his credit, among them Glazunov, Liadoff, Arensky, Sokolof and Wihtol; also Tscherepnine, Akimenko and Zolatareff.

As a composer, he has done much to prove the practicability of making effective use of Russian folk- themes; in his operas he has embodied the tales and customs of Russian mythology; in his orchestral pieces he has shown imagination and inventiveness in treating picturesque subjects. As an editor he has done much to further the knowledge of music by colleagues who were deficient in technical training; as a conductor he has furthered the cause of Russian music; as a teacher he has an enviable record of having fostered the leading talents of the generation succeeding . his own. His activity has been incessant in its productivity; he seems at present to be at the zenith of his powers.