From the earliest dawn of civilization musical instruments have been in use, and all our music-making machines to-day are descendants of those which were used in the remotest ages of antiquity. It is a far cry from the tamtam of the savage and the pipe of Pan to the organ and the pianoforte in their present stage of perfection, and the story of their development is an interesting one both to the antiquarian and the musician.

The first instruments used by man which might fully be called melodious were no doubt stringed instruments. These have always held an important place in the music of every country and people, whether their strings were plucked by the fingers or by plectra, or struck by some sort of hammer. The piano belongs to the last-named class of stringed instrument, but curiously enough it is the immediate descendant of the type with plucked strings.

The large dulcimer, which we so often find in ancient Babylonian and Egyptian sculptures, is the particular instrument out of which the pianoforte grew. It had a hollow body covered with parchment and was strung with many strings, and although extremely primitive and unsatisfactory from our point of view it formed the basis of all old military music and was played at all the great court ceremonials of the Assyrians. It was in Persia that the dulcimer made the first step in the evolution which was to transform it gradually into the modern piano. There it was made with a sounding board strung with wires which were played upon with two sticks.

The large dulcimer, which we so often find in ancient Babylonian and Egyptian sculptures, is the particular instrument out of which the pianoforte grew. It had a hollow body covered with parchment and was strung with many strings, and although extremely primitive and unsatisfactory from our point of view it formed the basis of all old military music and was played at all the great court ceremonials of the Assyrians. It was in Persia that the dulcimer made the first step in the evolution which was to transform it gradually into the modern piano. There it was made with a sounding board strung with wires which were played upon with two sticks.The Italians developed this construction still more in the Middle Ages and made the dulcimer long and flat so as to rest upon the knees of the performer.

Soon after this—for the sake of convenience—a keyboard was added to it, which, of course, was a great advance. It was then placed on a narrow oblong table and was thenceforth known as the clavichord. Its mechanism was of the simplest, the sound being produced by brass pins or tangents, as they were called, fixed into the keys which struck the wire strings. In spite of its very rudimentary construction and thin, tinkling sound the clavichord survived until well into the last century, and even inspired some of the greatest composers to write sonatas, preludes, and fugues for it. Bach wrote his greatest works for it and declared that he “found no soul in the clavecin or the spinet, and that the pianoforte was too clumsy and too harsh to please him.”

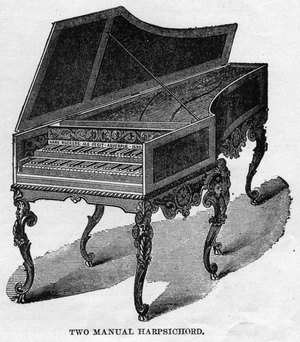

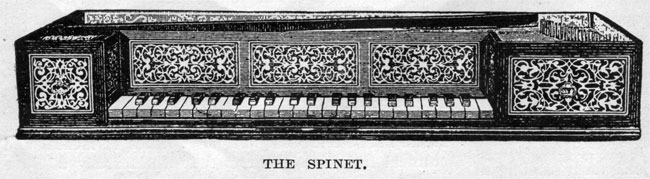

Next came the spinet, or virginal, which was furnished with little quill plectra with which the strings were plucked instead of the brass strikers used in the clavichord. Its tiny mechanism was very ingenious, but the sounds produced by it were mechanical to a degree, and the desire for greater expression led to the addition of several sets of strings and to the providing of a second keyboard. This improved spinet was called a harpischord (sic), and was often a very beautiful instrument. Great skill was expended upon its construction, and the decoration was often rich and beautiful in its effect. Its case was a small and attenuated form of our modern grand piano. Handel’s spinet, made by John Hitchcock, of London, in 1710, is still to be seen in the South Kensington Museum.

Italian and German makers now replaced the quills of the harpsichord by hammers and gradually overcame the many problems presented by its construction until Sebastian Erard, a French instrument maker, gifted with great mechanical cleverness, contrived a mechanism far in advance of all previous ideas, and from his invention the “action” of our day has been developed. The Broadwoods also did much to develop the power and tone quality of the instrument, and the manufacturer of pianofortes came to be one of the world’s industries, and Germany, France, Austria, and England were all doing their best to improve the popular instrument. The demand for greater power led to the introduction of the massive metal framing made necessary by the increased strain of the steel strings. In the matter of increased strength and solidity, qualities which add power and sonorousness to the tone, American inventors and makers have contributed much to the development of the instrument.

These are the outlines of the history of the horizontal, or grand piano. The upright pianoforte so familiar in the modern household is a thing of comparatively recent introduction. The earlier forms, introduced about the beginning of the nineteenth century, were much larger than our present convenient instrument, which came into vogue some fifty years later. The construction of an upright piano differs very much from that of the grand piano and it has been subjected to many changes of design; in fact, it is only within the last fifty years that it has been made the beautiful and excellent instrument that it now is. The pianoforte has been brought to perfection as the result of the labors of many lifetimes.

Modern pianoforte-makers are devoting much attention to the adornment of the exteriors of their pianos. These are now made in every kind of wood that is used for furniture and decorated to “go with” every period style in existence. In the past many of the great artists such as Cipriani, Angelica Kauffman, and Van der Meulen exercised their skill on the decoration of pianos, and some of the old cases covered with their lovely paintings still exist.

One charming old spinet still in existence is decorated with pictures of saints and angels singing and playing upon all sorts of quaint obsolete instruments, “sweet Saint Cecily, who taught the organ-pipes to blow,” in their midst, playing an Italian dulcimer. The most gloriously-decorated piano cases are, of course, those by or after Vernis Martin, the great decorator of the Louis XVI period. The exquisite coloring and wonderful lustrous sheen of his piano cases have never been surpassed, and they are perhaps the most magnificent ornament that any drawing-room could have with their beautifully-blended reds and greens and amber enriched by touches of gold.