When we listen to the interpretation of a great artist in song, it is not necessary to the full enjoyment of the work that we make an exhaustive analysis of how it is done; but if perhaps we are also vocal students and singers we may do this, as far as our ability will permit, to the end that we may improve our own interpretation, and base our study of expression on certain broad principles of groundwork which apply to each and every singer.

It is said that Nature abhors a vacuum. It may be also said that, musically speaking, she abhors a monotone. The line of beauty is curved, not a straight line. Even the most beautiful tone falls on the ear if delivered without gradations of power or tempi. The Italians knew this when they laid such stress on the study of the messa di voce, or the crescendo and diminuendo. The singer should feel that every tone should continually approach or recede from a climax of intensity and power. At the same time it must be observed that the last-mentioned characteristics are not necessarily synonymous. The crude tone may be loud and exhibit more or less power, but intensity in a high degree is characteristic only of the thoroughly cultivated voice. Of course, these qualities may be mixed more or less: the artist varies the amount of each according to the expression desired. Physiologically speaking, it may be said that power is developed more through a crude force of breath; intensity requires a stronger and more delicate contraction of intrinsic throat-muscles.

This, then, is the “lost art” of song, the “bel canto,” of the old Italian masters, as opposed to the declamatory style of the Germans, the “brittle staccato,” as Mr. Henderson calls it, employed by this class of singers. With the former the diaphragm contracts and relaxes slowly, steadily, continuously; with the latter its action consists of a series of spasmodic jerks; the intonation instead of being clear and well defined, takes upon itself the indefinite character of the speaking voice. As expressive types of these two classes of singers, one has only to compare the work of M. Jean de Reske, with that of M. Van Dyck.

To make use of the crescendo and diminuendo artistically requires such perfect control of breath and throat-action, that the most delicate and almost imperceptible gradations of power and intensity shall be at the command of the singer. It is sad to relate that the familiar expression-marks < indicating crescendo, and > indicating diminuendo, as printed in the ordinary editions, are frequently misleading, and as such must be disregarded by teacher and singer. The most common error that I have noticed in relation to these marks is that the sign > is used when the correct marking would be < > . This will be found especially in many editions of church music. Composers and music-type-setters are frequently careless as to the exact placing of these marks, and the singer must at times make use of his own judgment, rather than the exact marking of the piece.

In addition to the enhanced beauty of expresssion (sic) which a true observance of the crescendo and diminuendo lends to the voice, too much stress cannot be laid upon the restful and recuperative influences on both singer and listener which follow the proper use of the mezza or medium voice, and of the diminuendo. A monotonous mezzoforte tone is tiring to the throat of the singer, and to the nerves of the hearers. It is said that even the heart rests between pulsations; so even is the smallest interval of rest grateful to the throat and breathing muscles. The phenomenal endurance of many great singers is due to the judicious use of these little periods of rest. It is safe to say that Jean de Reske would not be singing as he does to-day had he not carefully conserved his voice in a manner that the most artistic rendering always demands. A forte tone is effective only as it appears as contrast to the piano quality.

If we look carefully over a verse of poetry we notice that it is made up partly of words of greater prominence or significance than others. These are connected with each other by little words of less importance, generally prepositions, conjunctions, articles, words of one syllable, and the like. Now, in reading the same properly aloud greater stress is laid on the more important words, the little ones being passed over with light and unaccented voice. If the composer has properly wedded the words to musical tones, the same system of grouping will be observed, making use of the infinitely greater variety of expression, to which pitch, length of tone, quality, vowel shading, etc., lend themselves in music.

What are the characteristics of the more prominent tones in a musical phrase? The long and the high- pitched tones belong to the most prominent words in the phrase. Length of itself is a form of accent, as is pitch, the highest pitch conforming to the greatest power, or the climax. Hence we divide the ordinary musical phrase into three parts: the beginning (piano), the climax (forte), and the anticlimax or close (piano). Some phrases close at the climax, but the ordinary phrase may be divided as above. If any of the tones are of sufficient length, and so isolated as to admit of the complete messa di voce ( < > ), then we have the characteristics of the entire phrase exhibited in diminutive upon the single tone. Similarly, we frequently find the entire musical period or sentence constructed like an exaggerated phrase. The first phrase is repeated at a higher or lower pitch, indicating crescendo or diminuendo, followed by still higher pitch as a climax, with return to lower pitch for closing, or anticlimax.

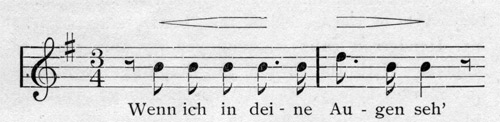

The following excerpt from Schumann’s “Wenn Ich in deine Augen seh” will illustrate:

This, the first phrase of the song, should be given with gradual and continuous increase of intensity and power upon the repeated tones up to the D of the second measure, which is the highest tone and the climax of the phrase. The anticlimax, which is short, occurs upon the two B’s following. The repetition following at lower pitch is somewhat less intense.

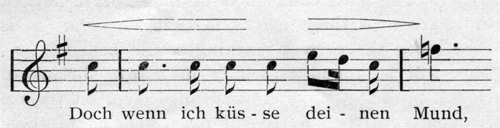

The third phrase, however,

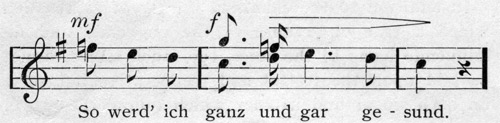

is of increasing power at higher pitch, closing without anticlimax. Still further climacteric is the fourth phrase or end of the half-period:

There we have a half-close, which takes place at the climax. The complete close at the end of the period is anticlimacteric, or piano, and at lower pitch.

The technic of tempo and rhythm will be considered later.—Henry W Giles.