A MOZART EVENING.

One of the most delightful phases of Mozart’s life was his strong attachment to his home, especially in childhood years. He loved his father and mother, learned his sister Nannerl’s lessons, was proud of her talent, and never ceased to speak thoughtful words of his father, who not only taught him, but set aside his own ambition to learn, in order that he might unselfishly attend to Wolferl’s education. When the readers of this page study Mozart’s life carefully they will not fail to note with what affection and loyalty the family watched the gifted boy, how they sacrificed all to his development, how even the talented Nannerl gradually withdrew from that public recognition which she believed was more particularly the right of her brother.

No pleasanter study for an Etude Children’s Club could be found biographically than that which has to do with Mozart’s childhood. Interesting as his life is throughout, it is especially so during his childhood and early youth. Assuming a club to have agreed to take up this study, the following helps will prove interesting:

1. Chapters on Mozart in Mr. Tapper’s “First Studies in Music Biography.”

2. In the same author’s “Pictures from the Lives of the Great Composers for Children,” pages 125 to 172.

3. “Letters of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.” With Nos. 1 and 2 there are questions on the text, of a nature to draw out one’s knowledge of main facts.

The “Letters” are delightful sketches of the composer and of his environment drawn by the skilled hand of the master himself.

A club-meeting could provide an interesting program, to include: 1. A sketch of Mozart’s childhood years, to be written by a club member. 2. Five or more of Mozart’s first contributions for piano—admirably printed (and dated) by Breitkopf & Hartel. 3. His Violin and Piano Sonatas (his first published compositions, if I remember aright). This last was brought out in Paris on the occasion of his first visit there.

A short biography of Mozart for the reader to take up after having finished such preparatory study as the above-mentioned books furnish is that by Dr. Gehring. The volume has one serious fault, however, which, no doubt, turns many a reader away

from it or proves discouraging to one who begins. The volume has no chapter divisions. There are one hundred and thirty or more pages closely printed and without a break. But they are worth reading, and the young student is urged to take up the book for its merits. It is a good stepping-stone to more pretentious works, the best of which is that by Otto Jahn.

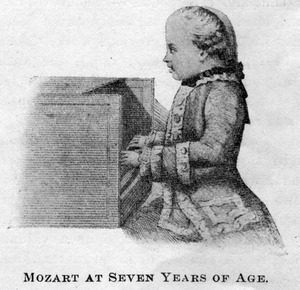

A friend of the Mozart family has said of Wolferl’s childhood that the moment he gave his attention to music his interest in all else ceased; no game could attract him then. This same friend described him thus: “As a boy you were rather earnest than childlike, and when you sat at the harpsichord, or were otherwise busy with music, no one ventured to jest with you in the smallest degree. Your countenance even was so grave that many intelligent persons, seeing your talent so early developed, and your face always serious and thoughtful, were concerned for the length of your life.”

Although his life did not prove to be long, his face certainly showed more than seriousness. It was full of life and animation, especially when he was occupied with his own music and it went to his satisfaction.

His love for his father he expressed thus: “Next to God comes papa!” He wrote (when about twenty-one) very appreciatively about his father’s teaching and about his sister’s talent. In the presence of titled personages he was in nowise abashed. He jumped into the lap of the Empress of Austria; did “tricks” at the piano with the emperor; told Marie Antoinette that she was good and that he would marry her; and when the Crown Prince, Joseph, played a wrong note or two on the violin, he cried out: “Fie! that was false!”

One of the most delightful statements made about Mozart is that concerning Rücken. This was an imaginary kingdom of children which he had created while traveling. It was to be peopled only by children, and he was to be the king. He had it definitely arranged, and even a map of it was made for him.

The following chapter is founded on this delightful fancy:

THE KINGDOM OF WALKING-STICK AND FOOTSTOOL.

Before us there was a house that looked as if it had been picked out of a row of houses and set down on the stage where we could look at it without seeing ever so many others. On the door-step stood the happy

flute-player, with such a twinkling laugh in his eyes that the moment he looked at us everyone began softly to hum or to whistle his merry air. As he heard it, his smile grew even happier. He was standing before the door, from which, as he heard the music, he turned slowly, gracefully, even slyly. On the door we saw these words:

IN THIS HOUSE DWELLS A GENIUS UNSPOILED BY KINGS.

The trombone man played us the same trick as before, and when we turned again to the stage, not only was the flute-player gone, but we were inside of the house instead of outside. We heard a loud stamping of feet somewhere and a voice called:

“Open the door at once, or I shall have to break it down!”

You may be sure the door flew open without delay, and in rushed a horseman. He had a crown upon his head; in one hand he carried a sword. The crown wobbled a great deal as the rider rushed on, for his was a noble steed. It reared, and it pranced, and it kicked. Time and time again it nearly threw the rider off its back. But he was brave and courageous, and clung fast, guiding with a firm hand and a kind voice.

It was also a famous horse, this horse of the kingly rider. It had been to many countries, to great cities without number. Kings, and Queens, Princes, and all sorts of Nobles had seen it come and go. But never in all the years had one of these royal personages ridden it. Now, fully in control of the rider, it pranced on. Twice and thrice he put it around the room. A man, a woman, and a young girl were there watching. He commanded them out of the way, but further he did not deign to address them.

All at once he stopped short, dismounted, and let the horse drop to the floor. Placing a footstool on a chair, he fixed his crown straight on his head and climbed upon his throne; he was no longer a rider, but king of a kingdom!

What was the kingdom? It was the Land of Children; of children dark, and children fair; of children grave, and children gay; of children with eyes dark as night, and of others with eyes like a sunny day. Singing children lived in the Harpsichord; they were of merry lays, of grave songs, of happy airs! Under the Rocking-chair lived the Lullaby children; they were those who swayed to and fro, in dreamy restfulness, the livelong day; swaying, swinging, up and down, to the music of Harpsichord-children.

And there were ever so many others. By the window was the land of the Sunbeam-children; under the bed dwelt Slumber-children; Glow-children danced, and laughed, and frolicked in the fire—while in the book-case was the land of Story-children. Oh, it was a wonder-kingdom, to be sure!

And what of the King? He was stern and commanding on his steed, but kind and gentle on his throne. There was not a child in the kingdom whom he did not love with all his heart; more than all others, perhaps, the Harpsichord-children. If he but thought of them, they came trooping about him in twos, and threes, and scores, and hundreds; singing merrily, gravely, happily; answering his thoughts so perfectly and so quickly that even he, the King, was often surprised as he welcomed them.

All day the Sunbeam-children played about him; played about him until the Glow-children and the Story-children joined hands and danced in a merry ring; danced so hard, and so fast, and so merrily that the King’s eyes were full of surprise, so full of surprise, indeed, that they could hold nothing else; and he had to let his eyelids fall to keep the surprise safe within. Or was it that the Lullaby-children pulled his eyelids down? Well, it does not matter.

All day the Sunbeam-children played about him; played about him until the Glow-children and the Story-children joined hands and danced in a merry ring; danced so hard, and so fast, and so merrily that the King’s eyes were full of surprise, so full of surprise, indeed, that they could hold nothing else; and he had to let his eyelids fall to keep the surprise safe within. Or was it that the Lullaby-children pulled his eyelids down? Well, it does not matter.

“Dear, dear,” said Annette to the Boy, “some one is going to speak to the King. Listen hard so that we shall hear what she says.”

It was the young girl. She stepped up to him; took off his crown with gentle, loving fingers; laid his sword on the table, and leaning over to him said:

“Come Wolferl, dear; it is bed-time!”

* * *

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH.

In the October Children’s Page an invitation was extended to its readers to contribute a biography of Mozart, the composer represented in this issue of The Etude. December and January are important months in the story of Mozart’s life, for he was born in January and died in December.

In the October Children’s Page an invitation was extended to its readers to contribute a biography of Mozart, the composer represented in this issue of The Etude. December and January are important months in the story of Mozart’s life, for he was born in January and died in December.

It seems scarcely possible that the composer of such beautiful and satisfying music could have been born so many years ago—nearly a hundred and fifty! His music is so full of simplicity, of pure melody, of everything, in fact, that appeals to us as being right, that we almost consciously think it is music of today. Really it is music of to-day: that is, music for us to study, and learn, and delight in to-day and in years to come.

The Editor has received many biographical sketches of Mozart by readers of this page. Most all the writers relate that which attracted them most. Not many tell the story in order from the beginning to the end: a very desirable procedure, in many ways. One of the biographies received is printed here. It represents, perhaps, more good points than any other. And, again, it is a very creditable piece of writing, considering the age of the author.

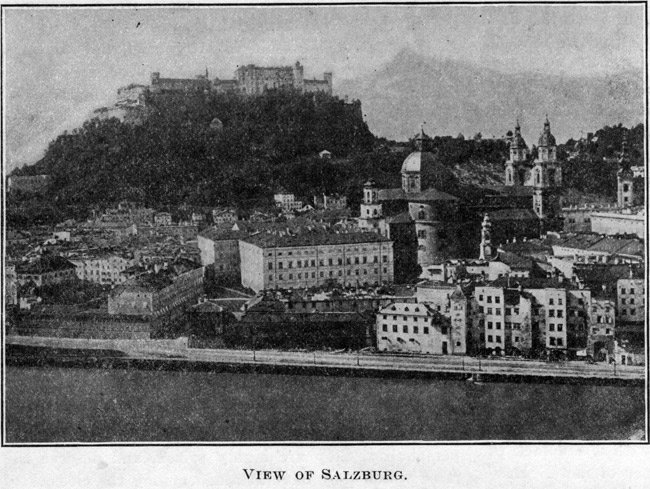

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg, in 1756. He was called a child prodigy. His father was a fine musician.

Mozart had a sister, Maria Anne; they were very fond of each other and spent a great deal of time together; she was always called Nannerl. When they were children together she was fully as musical as Wolferl, as he was called, but when he grew to manhood he surpassed her. Mozart began to compose small minuets when he was about five years old.

When he was about five years old his father came into the house one day and a wonderful sight met him: There sat little Wolferl with a sheet of paper all covered with daubs of ink. His father asked him what it was, and he said it was a concerto for the harpsichord, and Wolferl got up and showed him how it went.

He did not like to be praised after playing on the harpsichord.

He could not bear the sound of a trumpet, and always tried to avoid it; but his father wanted to break him of this, so one day he blew a loud blast on the trumpet and the boy immediately dropped on the floor in a convulsion. This may seem brutal, but he was always a loving father.

When Wolfgang was a small boy nothing was complete without music, and if they were playing with their little friends he always wanted some one to play or sing.

When they were about seven years old their father planned for them a grand tour. They went to Vienna, where the emperor and the empress were staying; when he saw the empress, a beautiful, kind lady, instead of kneeling to her he ran up and jumped into her lap and kissed her. She seemed very much pleased, and thought it a great favor. She had a small daughter, Maria Antoinette, who afterward became Queen of France; she seemed very pretty to our small Mozart. When he was walking across one of the polished floors he slipped and fell; little Maria Antoinette ran and sympathized with him, and he was so pleased that he said: “You are a good girl, and I will marry you some time.”

After that they traveled in many foreign countries, and met everywhere with the greatest welcome, and finally went back to Salzburg; they had been gone two years.

When Mozart was fourteen years old his father took him to Italy. This pleased the boy above everything. The Pope gave him an order of “The Golden Spur,” and he was called “Chevalier.” This pleased his father immensely.

When he was twenty-six years old he married Constance Weber, and they led a very happy life.

“Don Giovanni” was his greatest work, and the “Magic Flute” was probably next.

After awhile the young master began to get very ill, and he feared he was being poisoned.

And one day a man gave him a letter; it was an order to write a “Requiem,” a mass for the dead. And as he wrote it he was awed with the mystery of the request; it was for a nobleman who had lost his wife. After awhile Mozart told his wife that he was writing the “Requiem” for himself. And one winter night he gave his friends explicit directions how it should be finished, and bid them good-bye, and at one o’clock he turned his face to the wall and fell asleep, never to wake again in this world.—Catherine Gould (13 years old).

* * *

SYSTEMATIC PRACTICE.

The Children’s Page has never presented a contribution which was written by two authors. Here is one which says much about practice that is true. If all young players were of the same opinion, what a pleasant task it would be to learn about music! The authors of “Systematic Practice” are “aged twelve years each.”

The first to think about is where to practice; in a nice cozy room because it makes our thoughts bright and happy. We should have a good piano which is in tune. The best time to practice is early in the morning, when our thoughts are fresh, and all other times when we feel like playing for amusement. In this way we learn to play a great deal each day without getting tired. We find playing scales and exercises first is the keynote for all the rest of our day’s work.

When practicing think of what you are playing, do not look out of the window; one hour of practice should be a pleasure, and not a dread. Get to work and think out the hard parts in the lesson for yourselves. We will have this to do some time and why not begin now? We will not have our teachers with us always, but we do hope to have The Etude to read and to learn from, so we will have better ideas on this subject when we are older.—Ruth Franks and Ethel Murray.