By FREDERIC DEAN.

Mozart’s Position Unique.

Mozart’s position in the world of music is absolutely unique. There have been other musical prodigies, but never one so gifted. There have been others who were composers in their early youth, but none so remarkable. There have been other great music-masters, but none who attained distinction at so immature an age. Gluck at fifty started a new school of music. Mozart, as a lad, carried Gluck’s ideas to completion. Haydn, the father of the symphony and kindred classic art forms, was a mature man of the world before he sketched his first symphonic model. Mozart had completed a symphony when a child of eight. Beethoven, when pressed for the completion of one of his large works, replied: “I must have more time.” Mozart wrote his last three symphonies, those in E-flat, G-minor, and C (“Jupiter”) during a single summer, devoting but thirty days to each. Before his day instrumental music was an amusement simply; the orchestra, a toy. Mozart perfected the order planned by Haydn, and gave permanent form to the various parts of instrumental speech, and to-day we parse a symphonic phrase according to Mozartian grammatical rule. In the realm of operatic music he was the same life-giving power. Born a melodist and arriving at Paris in the midst of the Gluck-Piccini warfare, he borrowed of Italy “all that pertains to melody,” but turned elsewhere for truth of diction; and although he disagreed with Gluck about “the nobility and pre-eminence of poetry,” and was first, last, and all the time -a musician, and not a dramatist, he left in “Don Giovanni” a perfected form of music-drama that is, after a hundred years of imitation and detraction, the purest, most abiding work known to the operatic stage.

The Spirit of the Time.

At the time of Mozart’s birth all Europe was in the ferment of an intellectual upheaval. “To think” was the verb of the day. In his own branch of art a new activity was apparent. The sound-wave of intellectual music was to sweep the world, and Mozart was the instrument by which it was to be brought to the ken of men. Bach had left earthly musical activity but a half-dozen years before Mozart entered into it. When Handel died this new musical apostle was but a babe of three, but he had already left the nursery and taken his first step in the path trod by the giants that came after him: Beethoven, Schumann, and the rest. Through a childhood of marvelous precocity and youthful triumphs Mozart passed to an early manhood, tasting but few of the sweets of success before he was taken back to the gods, leaving behind an imperishable and an immortal fame such as few have won in a busy life of twice the span of years allotted to him. He came into the world dowered with talents the like of which had never before been known, he acquired, in his short life the most complete musical culture, and departed leaving behind him examples of melodic grace, of technical perfection, of musical forms that have been the pattern of all followers of the art from his time to ours. The characteristics of both the Italian and German schools were represented in him in the highest and most eloquent forms, and he was seemingly equally at home, whether writing for the sanctuary or the stage, for instrument or voice.

Environment.

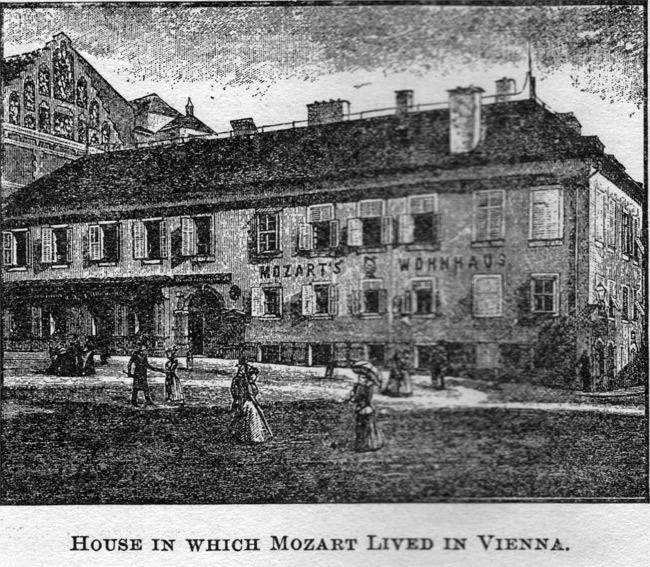

Man’s environment either makes or mars him. Climate is as responsible for our music as it is for our morals. Beautiful Salzburg made a fitting birthplace for this disciple of the beautiful. Mozart’s home-life fostered all that was good and true in him, and sweetened the first notes he put in musical order. He had none of the grinding poverty of Haydn in his early days, nor the discouragements of Bach and Handel. His musical gifts were cherished and brought to light, polished by judicious and careful education, and set before the world in their proper frame by loving, but by no means foolish, parents.

As was the case with his remote follower, Mendelssohn, music was early made, and adopted by him, as his life-work. He was as much at court in his boyhood as was Handel in his old age, and his minuets picture the quaint, old-time dances as graphically as Handel’s pompous choruses breathe the very air of the heavy Hanoverian dynasty. The sunshine of his early home was like that surrounding the gray-haired Haydn in his Esterhazy days, and his music reflects those joyous, happy hours as truly as do the later works of his friend and guide picture the light and warmth with which his last years were sweetened and made glad. Mozart exhausted the sunshine of his life in his early days. It was only after discouragements of the most disheartening nature, after years of poverty and pain, that he attempts to finish his “Requiem” before death claims him for his own.

His Impress.

Mozart is the most impersonal of all the great writers of music. He never parades his thoughts, his life, his joys or sorrows. But all the better able is he to describe in an impersonal manner either the musical thoughts intended or the traits of character to be pictured. His musical meanings are always plain and unmistakable; and whether you take a movement from the “Jupiter Symphony” or a scene from “Don Giovanni,” it tells its story as clearly as if by annotated text. Each phrase is chiseled out carefully and clearly. Every character is a silhouette. Human passions, like intricate fugues, were traced with a perfect accuracy of meaning and proportion, and with it all the musical language is the most beautiful ever penned. Mozart’s sensitive ear never lost its acuteness of perception, and when he says “Music ought never to wound the ear,” he speaks of his own delicate organ.

In Mannheim Mozart had the finest orchestra in Europe, and with this body of instrumentalists he experimented, improving it as it had improved him; simplifying and defining form as his ideas were expressed in musical language. He found musical figures distorted and confused, and arranged and clarified them, introducing clear, sharp outlines in beautiful formal construction. Like the magician of old, he had but to wave his wand over the turbid musical waters to transform them into streams of crystal purity.

Mozart was born as Haydn was winning his first musical spurs. During his short life of thirty-five years Cherubini, Beethoven, von Weber, and Meyerbeer were brought into the world and Handel and Gluck were taken out of it. Like a beautiful Greek faun, he danced upon the music-stage of life with a lightness and a grace never equaled before or since. His genius was so transcendent he scarcely needed to borrow from his predecessors, but gave with lavish hand of his own seemingly inexhaustible store to those who came after him.

Questions.

What was Mozart’s position in the music-world?

What were the characteristics of his music?

Compare him to Gluck. To Haydn.

Who were his immediate musical forbears?

What was the state in which he found instrumental music? How did he help it?

What did Haydn do, and how did Mozart supplement his work?

Name one of Mozart’s symphonies. How old was he when he wrote his first?

How long did it take to write the last three?

What was his rank among operatic composers? How did he differ from Gluck and Wagner?

Compare his early life with the later days of Haydn.

In what particular does his life agree with that of Handel?